That mysterious ruined island in Skyfall is real.

If you saw the 2012 James Bond film, you were likely as mesmerized as I was by the scene. Bond and Séverine are prisoners on a yacht, and as they sail towards the villain’s lair to meet their doom, a mysterious island emerges from sea mist.

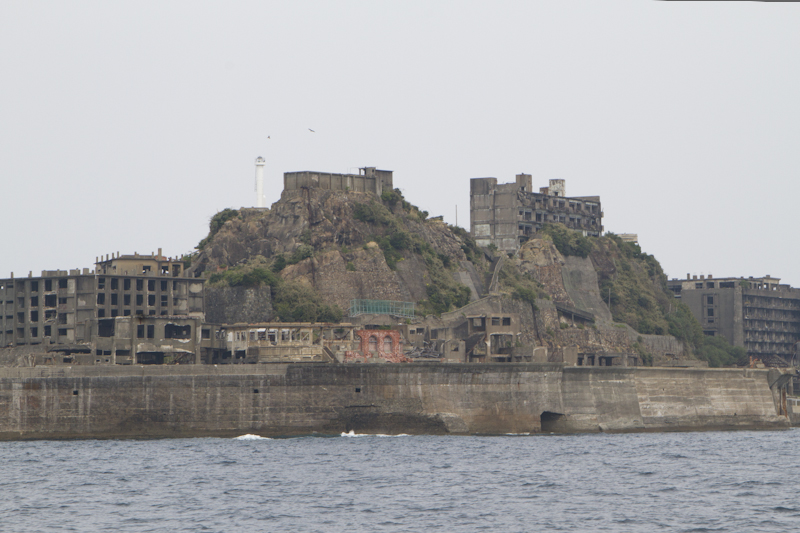

As the ship draws closer, we see that the island is crowded with abandoned concrete structures: an entire mysterious city lost somewhere out in the sea. And then their shoes crunch stones and broken glass as they walk through its creepy echoing streets.

I did a little research after I saw that film one chilly winter night in Brussels, and I quickly discovered that the island is real.

It’s located in Japan, near the harbour of Nagasaki. The movie wasn’t actually filmed in this place. The producers visited the location and were suitably amazed, but they concluded that the island was too dangerous and unstable for shooting a movie. And so they build a very convincing replica on a soundstage in London instead.

As luck would have it, my travels took me to western Japan earlier this year. And seeing this incredible abandoned place was at the top of my list when me and Tomoko spent a few days in Nagasaki.

The tiny island of Hashima is more commonly known by its nickname, Gunkanjima (“Battleship Island”), so called because it resembles a warship in profile.

It is located nearly 15km out to sea, beyond the mouth of Nagasaki harbour. And this abandoned island was once the most densely populated place on the planet.

You see, the world was powered by coal at that time, and a rich vein had been discovered beneath a tiny hunk of rock far out in the waves. Undersea coal mining was established on Hashima in 1887, and production and settlement increased year by year as Japan’s industrial modernization transformed the nation.

Mitsubishi bought Hashima in 1890, and in 1916 it began building the first of the apartment blocks to accommodate growing ranks of workers. At 9 storeys tall, this was also Japan’s first large concrete building.

The 6.3 hectare (16 acre) island reached a peak population of 5,259 people in 1959, stacked up on top of each other in crowded blocks and dormitories. To put it in perspective, this is a population density of 835 people per hectare (or 83,500 people per square kilometre) — 9 times the population of Tokyo at that time.

The island became a self-contained world, with schools, hospitals, shops, a cinema and a pachinko hall. It was a tightly packed maze of courtyards, corridors and stairs. But there was no room for trees in this grey, storm-lashed place. Instead, the residents carried soil onto buildings to make rooftop vegetable gardens.

As the men ventured below ground to hack out an income, the women and children lived their walled in lives. Babies were born on Gunkanjima, and children went to school. Neighbours worked together to hold seasonal festivals, to celebrate each other’s good fortune, and to provide support through life’s inevitable tragedies. They made the best of their situation, and their isolation drew them together — especially when the island was cut off by storms.

Between 1891 and 1971, miners ventured over 1,000m below sea level to excavate around 15.7 million tonnes of coal.

But the times were changing, and with the shift to energy production from oil, the demand for coal was running out. Especially from such an expensive, difficult to maintain place. The undersea reserves of Gunkanjima were running out too, and the mines were finally closed in 1974.

Everyone left, and Gunkanjima was abandoned to crumble away, battered by waves, salt air and storms for 35 lonely years.

The island attracted the odd urban explorer (check out this blog for some great photos), and fishermen who trolled the waters around its rocky outcrops. They came back with photos of abandoned television sets, dolls left lying in the dust, and initials carved on stained cement walls. The island was filled with the memories — and childhoods — of those who had lived there, and who one day up packed their things and sailed away.

But it wasn’t until the 2000’s that Gunkanjima became a sort of tourist attraction.

It was first opened to journalists and to select members of the media. And when the safety railings and cement walkways were finally completed, a tiny corner of the island — well away from the crumbling buildings and other structures — was opened to small, tightly regulated tour groups in 2009.

The story of Gunkanjima was mired in controversy, chiefly because of its wartime history. Korean and Chinese forced labourers were used to mine the undersea coal seams prior to and during WWII, and no mention of this fact was made on our tour.

But Gunkanjima finally gained UNESCO status in 2015 as part of Japan’s Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution. And rightly so, because this lonely place provides an incredibly unique look at life during the period of industrialization, in what was once the most densely populated place on the planet.

We rode out there early one morning on a tightly packed boat to get a look for ourselves. The foreigners had been segregated into a cabin at the front, in what was being billed as a special “VIP section”. I think in truth it was to herd them more efficiently, because of their tendency to ignore directions and wander off.

During the rolling 30 minute ride, a video displaying the history of life on the island looped over and over on an otherwise silent screen. Passengers chatted quietly in several languages, or sat grimly fighting off the approach of motion sickness.

And finally, the island hove into view, rising out of frothing grey seas exactly like the battleship which gave it its name.

Our boat swung around the island several times, and paused so passengers could take turns photographing Gunkanjima from the open top deck. And then we tied up at the dock — which is only possible in calm seas — and had a look around.

Visitors are restricted to a very short tightly controlled route, on concrete paths which have been fenced off with safety rails. During the course of our visit, we were given rote speeches on the history of this place while standing on a series of three broad viewing platforms.

In the distance, four men in white hardhats stood next to a wall, making notes on a clipboard and discussing the deteriorating state of the buildings. Several structures had collapsed completely during Gunkanjima’s decades of abandonment, and others have since been stabilized or restored.

The Japanese and foreigners were separated into two groups, and I drifted between them for a while until we saw a friendly worker who helped us make our escape from the gaijin. I can understand enough Japanese to follow along, and their guide was much better: an older lady who had grown up on nearby Takashima and knew the coal mining life.

I listened to her tales with one ear as I stared into the twisted alleys and crumbling walls of the buildings and desperately wished I was there on my own, free to explore every corner at my own pace, and to camp in an empty room as darkness fell.

I want to know Gunkanjima in solitude, as the sea winds moan through the empty corridors. Perhaps, in the lulls between the winds, I might be able to catch the echoes of laughter and conversations and the life that came before.

It used to be possible to pay a fisherman from nearby Takashima island to make the trip out in the predawn hours. He would drop you off for some exploring, and then collect you again before the first of the tour boats showed up to circle and take photos. But control of the island has tightened with the increase in tourism, and I saw what looked like several CCTV cameras up on the buildings, pointing down at the path.

And then the friendly tour company employee tugged on my sleeve and pulled me from my reverie. Our tightly-regulated 50 minutes was over all too soon, and it was time to leave. The others were already climbing into the boat, and me and Tomoko were the last ones on the viewing platform.

We avoided the foreign “VIP salon” on the return journey too, opting instead to sit on the exposed upper deck with the Japanese visitors, watching the island recede into the distance before it finally faded into the bowl of the waves.

Like many abandoned places, Gunkanjima takes a great deal of effort to visit. If you want to go in person, there are four or five tour boat operators to choose from. I recommend Gunkanjima Concierge. Make your reservation as early as possible — even as much as a couple weeks in advance — because sailings get fully booked, especially in the busy season. We got very lucky with a last minute cancellation.

Is Nagasaki just a little too far out of your way?

Don’t worry. You can still get a sense of this mysterious island from THIS promo video shot by Sony using a helicopter drone. And you can explore the streets and alleys from a distance thanks to Google Street View. Google sent an employee to Gunkanjima with a “street view” backpack in 2013.

I hope you take some time to check out the links I’ve included throughout this article. Those sites cover Gunkanjima both when it was a living community and during its decades of abandonment. It’s a truly fascinating place.

Photos ©Tomoko Goto 2016

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...