Palmyra sits far out in the desert, an oasis within what is now the war torn country of Syria.

When I went there in 2009 it was a rather forlorn place: a town of date palm plantations existing on the margins of the known world. But from the 1st to 2nd century, this desert oasis stood at the crossroads of civilizations, and the traces which remained preserved an art, architecture and religion that merged the Greco-Roman with local traditions and Persian influences.

Palmyra was already established as a caravan oasis when it came under the control of the Roman Empire around the middle of the 1st century AD.

It grew in importance because the trade routes which crossed here linked the Mediterranean world with Persia, India and China.

The main axis of the city was formed by a grand colonnaded street 1100 meters long, and the Romans gave this dusty desert town an agora, a theatre, an aqueduct, and a vast necropolis beyond the city walls.

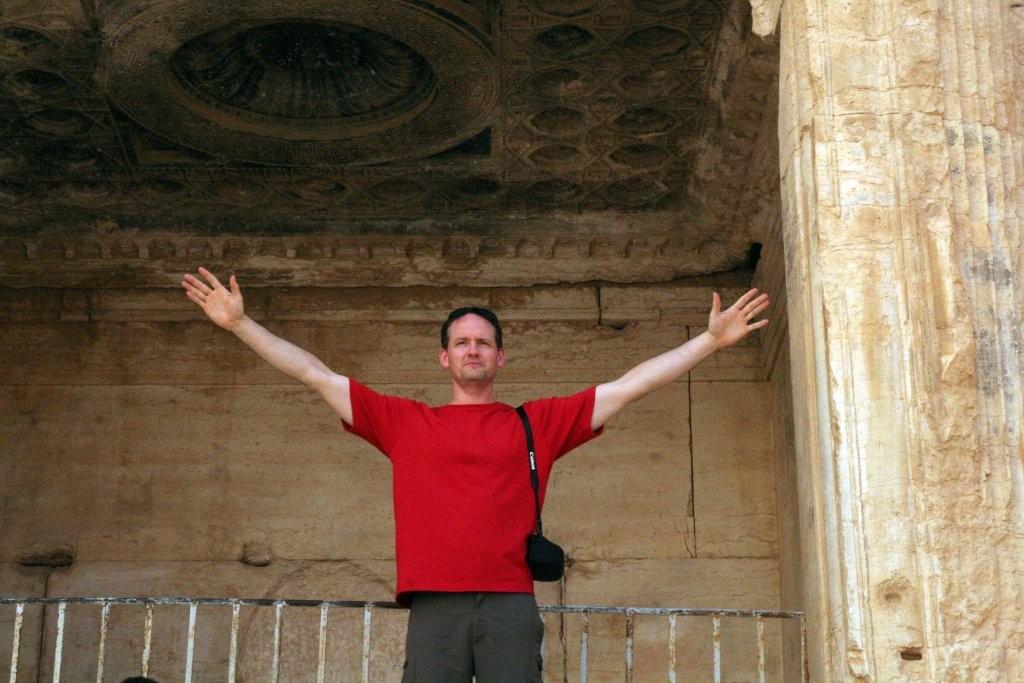

But it was the Temple of Baal which was the most interesting an irreplaceable ruin to come down to us. The city’s inhabitants worshipped local deities and clung to the old Mesopotamian and Arab gods. They built temples which were a strange and interesting synthesis of Near Eastern and Greco-Roman architecture, and the plastic forms of their beliefs provide us with some insights into the worldview of those Mesopotamia people whose agricultural revolution spread west, and whose thought eventually twisted and morphed into elements of Western civilization’s own later religions.

Palmyra changed hands many times over the centuries as the power of empires waxed and waned. It reached its height of power in the 260’s under King Odaenathus, and then Queen Zenobia, who rebelled against Rome and established the short-lived Palmyrene Empire. It was a deep-desert Roman outpost, a minor centre under the Byzantines, a larger town under a succession of Arab caliphates, and a small village under the control of the Ottomans.

The city fell silent for centuries, until something woke its memory up. It began to lure desert travelers in the 17th and 18th centuries. They journeyed there by camel, through a wasteland infested by bandits, simply to see a place that would come to embody their romantic neoclassical vision of the quintessential caravan city.

Perhaps the most famous among them would have been Lady Hester Stanhope, who journeyed there in disguise in 1813, dressed as a Bedouin and traveling with a caravan of 22 baggage camels.

My own journey to Palmyra wasn’t nearly as rigorous, and the dangers I faced were no more threatening than a sore lower back and a mild hangover.

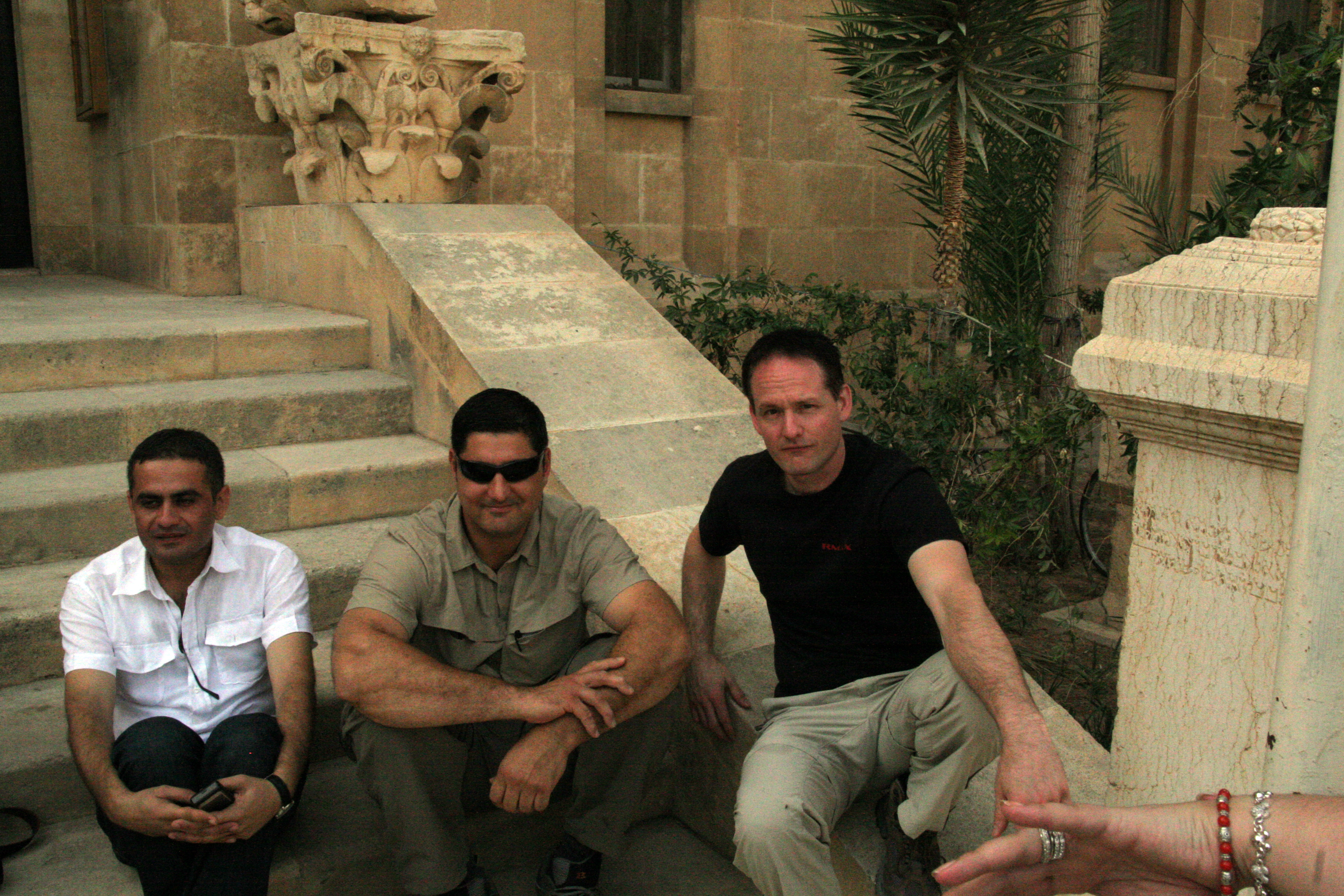

I drove there from Damascus in a well-worn minibus, with my frequent collaborator the photographer Jason George, and with several American friends. We were all writers, photographers, journalists and publishers, in Syria as part of a press delegation which had been organized by the ALO Cultural Foundation in 2009. Most of us had traveled together before, to Jordan and Egypt, and more recently to Turkey.

I had hoped to write about the Assassins, a bizarre religious sect from the time of the Crusades that had left castle ruins all over the country. It didn’t work out — which is a story for another time. But as a longtime desert traveler, Palmyra was the other highlight of my visit.

The desert began just beyond the outskirts of Damascus, and we seemed to drive for hours over dusty flats and through areas of low gravel hills. Everything had been painted in shades of brown. It was the sort of landscape that makes you thirsty just by looking out the window.

There wasn’t much out there apart from phosphate mines, natural gas industries, a military air base and a large prison which reputedly held political prisoners of the Assad regime.

Desert landscapes cause me to drift, and so I put in my headphones and listened to Hologram of Baal by The Church as the land unrolled around me like a film.

We stopped for coffee at a place called Bagdad Cafe 66 for cups of sweet tea and Turkish coffee as thick as tar. And we passed road signs pointing to Iraq, where a war was raging just over the border, somewhere out in the sands.

And then the green of date palms rose from the desert in the distance, and we were there.

We explored ancient tombs deep beneath the desert sands. I walked with reverence through the inner sanctum of the Temple of Baal. And we followed the dusty Roman streets to the theatre, where my friends and I sat in the audience baking in the sun, or tested the acoustics by performing long self-absorbed monologues on the stage below.

A sizeable modern town has grown up on Palmyra’s fringes, but we didn’t interact with it at all. In fact, I barely saw it. The ruins retained the magic that they had for all those explorers and Victorian age travelers who came before us. And there was so much more to discover. My only regret was that we hadn’t enough time.

A dark castle brooded over the oasis, high on a steep hill of raised bedrock just beyond the main ruins. It belonged to a much later period and had nothing to do with the ancient oasis, but it had been tugging at the edges of my vision throughout the two days we stayed in the town.

This fortress was built around 1230 AD, towards the end of the Abbasid caliphate, by an emir of Homs named Al-Mujahid Shirkuh II. But it is known as Fakhr-al-Din al-Maani Castle today after an emir of an esoteric ethnoreligious group called the Druze who extended their domains to Palmyra in the 16th century.

When our hosts drove us up the hill to soak in the gentle rays of a desert sunset, I broke off from the group and walked quickly around the castle’s perimeter in search of an entrance. And then I crossed the drawbridge over a dry moat and climbed to the castle’s highest point.

The entire town was spread out below me: the pale remains of the Roman roads, the squat temple, and the dark green stain of the date palm groves which formed the only colours in this brown shaded desert world.

I liked Palmyra because this was a community that had always gone its own way; when Rome went Christian, the Palmyrenes clung to Paganism. And Palmyra also represented a dream. A vision. A mirage. A journey itself, where the destination may or may not live up to the hardships of your travels.

At the time I couldn’t imagine that just a year and a half later someone would rise up to challenge what felt like a brutally secure police state, or that they would attempt to overthrow Assad’s regime. And I would never have believed it could go on for so long, and that these people who had shown me and my friends such hospitality and such welcome could have suffered like this.

Many of the precious remains of this civilization — and of this irreplaceable monument to our collective past — were destroyed in 2015 and 2017 by a brutal group of religious fanatics called ISIS because these ruins somehow didn’t agree with the Bronze Age belief system they embrace.

When they occupied Palmyra, ISIS purposefully dynamited the Temple of Baal, the Temple of Baalshamin, several of the best preserved tower tombs (including the Tower of Elahbel), the Arch of Triumph and the Tetrapylon.

They turned the ancient theatre into a public execution ground. And they brutally beheaded the retired chief of antiquities, an old man called Khaled al-Assad, after torturing him for a month in an unsuccessful attempt to find out where he had hidden the city’s treasures.

As the iconoclasts destroy these precious traces of our collective past deep in the desert, their followers ram lorries into innocent pedestrians in Europe’s great cities, bomb nightclubs, and murder journalists for having the nerve to draw a fucking cartoon. And throughout it all, our leaders can’t even admit that this is religiously-inspired violence. That one’s belief system or ideology leads to actions.

This violence and destruction will get much worse as we play out yet another act in this two thousand year old saga of Bronze Age religious conflict. And much more will be lost in the name of imaginary gods.

I’m so grateful I saw Palmyra while I could. Travel to those places which inspire you this year — buy a ticket right now. And don’t take it for granted that they’ll still be there, or that you will. We are living in turbulent times.

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...

Wonderful article – wise advice.

I’m so grateful I was able to see Palmyra before its pointless destruction.