Lawrence Millman is the author of eleven books, including Northern Latitudes, Last Places, An Evening Among Headhunters, and Lost in the Arctic. His travel articles have appeared in such magazines as Smithsonian, National Geographic Adventure, The Atlantic Monthly, Sports Illustrated, and Islands.

He has made 30 trips and expeditions to the Arctic and Subarctic, discovered a previously unknown lake in Borneo, and has a mountain named after him outside Angmagssalik, East Greenland. He is a Fellow of the Explorers Club.

I first encountered Millman’s work many years ago in Best American Travel Writing 2001. His story of Pantelleria stuck in my head ever since, hovering at the back of my mind long after I’d transposed the location to Lampedusa.

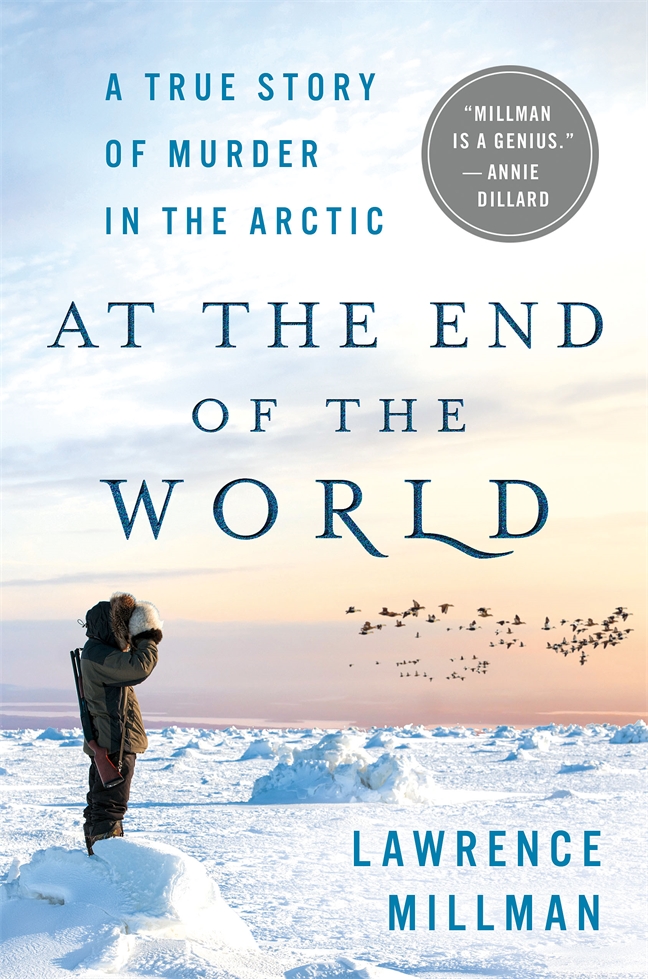

It was with great delight that I learned of his new book and secured an advance copy. At the End of the World is the story of a series of murders that occurred on a remote group of islands in the southeast corner of Hudson Bay in 1941. It is also an eloquent lament for a dying way of life, and a prophetic warning about our own dangerous shift from the natural to a virtual world.

I spoke with Lawrence Millman about travel, the new book, and how technology is changing us despite our obliviousness.

========================

Q: What does this quote by Charlie Parker in the epigraph mean to you?: “If you don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn.”

A: It means that actual experience is more important than knowledge gleaned from the classroom or the Internet. I read any number of books about the Arctic where the author never went to the Arctic, but relied on second or third-hand information. Thus the books seem simply like jobs of recycling.

I’ll give you an example. A New Yorker writer named Alec Wilkinson wrote a book about the 1897 Andrée balloon expedition to the North Pole (The Ice Balloon), but he seems not to have gone any farther north than Stockholm. Another example: California writer Jennifer Niven. She wrote a book entitled The Ice Master about an unpleasant overwintering on Siberia’s Wrangel Island, but she never went any farther north than northern California. Both these books seem empty to me — nothing coming out of their horns.

Q: Have computers/technology changed the way we see the world?

A: In At the End of the World, I wrote: “Seated at a computer, you may think you’re reflecting your own thoughts, but you’re really only reflecting your device’s algorithms.” This is perhaps a bit polemical. After all, at least a part of you may be reflecting your own thoughts…or reflecting some of the thoughts that haven’t been compromised by the computer itself. For recent studies show that the brains of Internet addicts contain roughly the same amounts of abnormal white matter as the brains of drug addicts.

In the book, I suggest that the way we see the world has not been changed so much as obliterated. Look at all the folks wandering about and affixed to their iDevices or the cellphones. A tornado could pass in front of them, or a 20 foot high, 14-legged extraterrestrial could be sashaying in front of them, and they wouldn’t be aware of it. Their only world is the one on their iDevices…or iGods, as I call them in the book, which — no surprise! — is anti-God.

Q: Do you believe that non-Western cultures have a more accurate view of the world?

A: Not more accurate, but simply different, and (I forget who’s responsible for this epigram) “Difference is wanted to make a world.” Without difference, the same-ness of our species would be — and increasingly is — dull beyond belief.

Q: What value does travel writing have for us as a species?

A: First of all, I don’t consider myself a travel writer. I write about places and my experience of them. Travel writers pen their words to attract tourists, whereas I pen mine to keep tourists — especially corpulent American ones constantly brandishing their corporate plastic — at a distance. As for the value that my sort of writing has for us as a species, I like to think that I’m putting a halo around cultures that have remained different from each other. But — see my answer to your previous question — those cultures are rapidly becoming the same.

Here’s an example. Several years ago, I was on a quite remote island in the Banda group in Indonesia. In a small village, a number of people were watching an episode of “I Love Lucy” on a TV propped up on a pedestal, and none of them were laughing. Why not? “Because they would like to own that furniture,” my guide told me.

Q: In your book, you express some rather scathing views of Christianity. Do you reject other religions, too?

A: I agree with Karl Marx that “Religion is the opiate of the people.” I suspect that Groucho Marx would have agreed with Karl and me here. For there’s something quite comic about a guy who’s doltish enough to get himself impaled on a pair of crossed sticks or also something comic about domesticated bovines being considered sacred, as they are in India. But there’s one religion I like: animism. For it puts its deities in this world rather than somewhere up in the sky.

Q: Do you have any sort of spiritual beliefs?

A: Whenever I hear the word spiritual, I run for the proverbial hills. It suggests religion in all its nonsensical abstraction, and I prefer palpable reality. Note: I do like so-called Negro spirituals, though.

Q: Were you born in the wrong time and place?

A: I’m a barouche and droshky guy, not a car guy, and I use a pen or pencil to write my books, so — yes — I feel I was born maybe a hundred years too late. My friends would disagree: they think the Bronze Age would have been more appropriate for me… and, in a way, they’re right. I’m a hunter-gatherer rather than a consumer (any government that supports consumerism should be brought down!). I go down to the shore and gather mussels, or I go into the woods and gather mushrooms, but I need to be dragged kicking and screaming into most stores and supermarkets.

Q: Your book is largely about the clash between so-called primitive peoples and ourselves. Do you think other modes of seeing the world than ours will survive? Is there any hope?

A: Alas, I feel there’s little or no hope. Let me give you a hypothetical example. Let’s say you’re a teenage Inuk named Ryan Tingaujuk living in Nunavut, and you know only a few words of Inuktitut. But why should you know Inuktitut? After all, you’re primarily interested in rap music. Meanwhile, your grandfather, a tradition bearer, is living with your family, and you can barely understand a word he says. He’s talking about things like ullisaqtuq (waiting all day at a seal’s breathing hole) and ipakjugait (the surface striations of snow), not rap music. Will his lore survive? Probably not, although academic anthropologists would say that it doesn’t matter because knowledge is constantly evolving, and rap music in its Inuit incarnation has simply replaced, for instance, drum-dancing. Of course, academics are usually funded to come up with ideas like that…

Q: Is fear of technology a generational thing, and are older people being left behind?

A: It’s no longer a generational thing. For instance, I now see plenty of older people swaggering around with iDevices or playing with those devices in restaurants while ignoring their food. Recently, I met with an older writer friend, a man of some eminence, and at least fifty times (I’m not exaggerating) during our several hour meeting, he pulled out his iDevice and googled something we were talking about. Has actual conversation become a thing of the past?

Q: You quote Upsagan as saying “So much is being lost.” Is anything being gained?

A: Yes! So many people now have myopia from staring at their screens that eye doctors are gaining more and more lucre; and large corporations like Facebook are becoming richer than anything a Rockefeller ever dreamed of…

Q: You cite Edward Casanova as saying that the greatest migration in human history is the current move from the real world to the virtual world. Is this also an extinction?

A: Everyone is so devoted to their screens that they’ve become completely oblivious of the natural world, and if you don’t see that world, why would you want to preserve it? Not having their habitats preserved, one species after another will go, no, is going extinct. Sic semper transit gloria mundi!

Q: You’ve traveled to the farthest corners of the world, but you continue to return to the North. What is there about this point of the compass that draws you?

A: I prefer Nature to people or at least crowds of people, and in the North there’s more of the former than the latter. Also, the denizens of the North — Cree, Inuit, Gwich’n, etc. — are more or less obliged to live with Nature rather than, as they might in a large city, live with stop signs, traffic lights, and automotive emissions. Let me add that I prefer being cold to being hot. You can always dress for the cold, but there’s only so much clothing that you can take off if you’re hot. Of course, cold is rapidly becoming hot, so neither I or anyone will be in a position to choose in the not so distant future.

Q: Mycologist and travel writer is a strange combination. How on earth did you develop such an interest?

A: I developed an interest in mycology from hanging out with northern First Nation people, who traditionally use fungi as stiptics, as fire starters, as insect smudges, and as a means of getting rid of evil spirits. This intersected with my writing about Place because it offered a window on individual cultures. But, truth to tell, I’ve always been interested in fungi, along with bugs, plants, birds, and beasts, because I’ve always preferred being outdoors to being indoors…

Q: What are your hopes for your writing?

A: That I continue to delight in putting pencil to page; that I will continue to find publishers eccentric enough to publish me; and that my writing will occasionally preach to those folks who are outside the choir.

Q: What would I find on your bookshelf now?

A: Can Life Prevail? by Pentti Linkola, An Intimate Wilderness by Norman Hallendy, The Kingdom of Fungi by Jens Petersen, Stand Still Like a Hummingbird by Henry Miller, Silent Snow by Marla Cone, Postcards from Ed by Edward Abbey, Maine to Greenland: Exploring the Maritime Far Northeast, by William Fitzhugh, Vagrant Viking by Peter Freuchen, and Shroom by Andy Letcher.

Q: You’ve been instrumental in getting several forgotten books and writers back into print. Why is this important to you? Did you choose the books, or were they assigned to you?

A: Some of these books you’re referring to are Snow Man (Malcolm Waldron), The Jungle and the Damned (Hassoldt Davis), Two Against the Arctic (Ejnar Mikkelsen), A Woman in the Polar Night (Christiane Ritter), and The Last Gentleman Adventurer (Edward Beauclerk Maurice). In each instance, I chose the book, and I chose it because I felt it was not only worthy of being reprinted, but also because I felt it was better, much better, than most books written by current authors. Otherwise, such books would have gathered dust in libraries, and then — like many older library books — consigned to a dumpster.

Perhaps, too, I’ve been active in getting such books reprinted because I hope someone will end up reprinting my books when I am gathering dust, too.

========================

At the End of the World is a portrait of the vanishing places in our own Canadian North, and an uncompromising warning about a technological future that is changing us in ways we’re failing to see until it’s too late. It is available January 2017 from fine booksellers everywhere.

*All photos were shamelessly poached from Millman’s Facebook page.

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...

Fun interview! Love the frank conversation about devices, religion, and fungi.

Thanks Eva. I highly recommend his books. Start with Last Places, it’s brilliant.

Speaking of fungi, you might enjoy this semi-related article https://munchies.vice.com/en_us/article/qknnnx/this-shit-is-a-delicacy

You identify me as a mycologist, and there I am, holding a moose scapula!!

Jeez, everyone knows that. It says “moose scapula” right below the photo. It’s a good thing you weren’t holding up some sort of obscure mushroom!