This is the seventeenth in a multi-part blog on North Korea. You can find the others here

We said goodbye to our brave military escort at the DMZ, thankful that they’d protected us from the imminent danger of American attack.

We made one last stop on our way back to the capital, just outside Kaesong city. It was reputedly the tomb of an early Korean king and his Mongolian wife, but as with everything else in the DPRK, nothing could be taken at face value. North Korea has been known to fake archaeological findings to support whatever version of history is the current party line.

Even if the physical site was authentic (and I believe it was), who knows how much of the interpretation was propaganda? The history of the Koryo Dysnasty—one of the founding kingdoms of Korea—is politically charged. The North believes that if they can claim control of that history, they can claim the right to lead a reunified Korean peninsula.

To the best of my knowledge, this burial mound was the only ancient tomb known to have survived the bombings of the Korean War. But despite my normal interest in history, I didn’t want to be there.

The sun beat down on the site like a hammer, without even the mitigating hope of a breeze. I followed along at the tail end of our group, dragging my heels alongside an equally deflated Norwegian. I’d become sick to the gills of monuments, propaganda and especially stories about the Leader, and Jon felt the same.

As we plodded along in our sweat soaked misery, Jon whispered all the idiotic comments he wanted to ask our guide. He looked so sincere, and his Norwegian accent pushed it over the edge.

“Why is it that we never see the Leader? Is it because he’s so fat and ugly?”

And, “I have a question. Last night I had this dream that I was having sex with the Leader. Is this normal?”

I could picture so clearly Jon asking these questions in sincere tones, and the look of absolute horror that would freeze on the face of our guide.

We were cracking up like school kids, trying desperately to keep a straight face while stifling snorts of laughter. Contagious hysteria wasn’t far off.

I said, “You know that blister on my foot? Last night the skin peeled off and… it was… it was in the shape of the Leader!”

I didn’t realize until we got back to Beijing the constant pressure we’d been under. Always having to be careful of what we said, the awareness that we were permanently under surveillance, every conversation listened to, and the seriousness of the North Korean guides with their relentless badgering propaganda. It was finally beginning to pile up.

One of the other guys drifted to the back and warned us to keep it down. If the North Koreans heard any of our jokes about the Leader, the least they would do was deport us immediately.

But I no longer cared what happened to the trip. I’d seen the DMZ and I was leaving the next day. Deportation would simply mean a couple less Communist monuments to suffer through.

The holes in the cracks of the regime continued to reveal themselves. On the drive back to Pyongyang, we stopped at a rest area that had been built to straddle the empty highway. There were of course no customers, only a few bored workers sulking in dark corners of empty rooms.

I happened to look into the kitchen on my way to the washroom, where I saw three workers filling plastic water bottles from a tap and re-sealing the tops with a paper clip and a lighter. They looked guilty when I caught their eye, but that didn’t stop them from trying to sell us those same bottles a few minutes later.

Back in the city, we were forced to make an unplanned detour because several main roads had been closed for the national holiday. We passed through semi-rural sections on the outskirts of Pyongyang, where the buckled tarmac was like one prolonged act of god. We didn’t see any other vehicles, only people walking down the nightdark centre of the road.

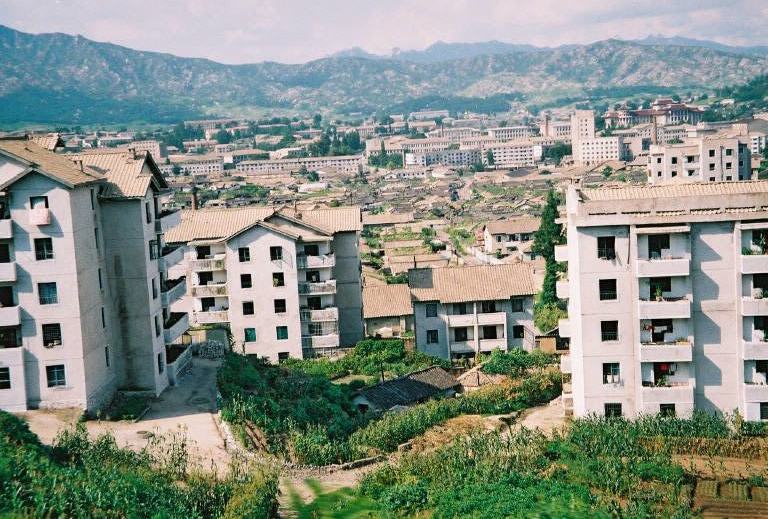

The housing areas of the outskirts were the diametrical opposite of the marbled grandeur we’d been shown in the city. Crumbling cement dwellings clustered around shared courtyards. Many of the houses were completely overgrown with plants and vines, as people tried to supplement their meager diet by turning their roofs into makeshift gardens. Behind one house, in a little yard surrounded by ruined walls, I saw a woman and child squatting beside a pile of coal, breaking lumps off with a hammer.

Soon after that, we passed what must have been a black market. Our minders jumped up and ordered us to put away our cameras, and they refused to answer questions. The quick glimpse we caught revealed a government soldier with a rifle standing guard in front of a little walled courtyard. Inside, people looked to be buying and selling with paper money.

I found out afterwards that the government turns a blind eye to these unofficial markets because they’re just about the only thing staving off more widespread starvation. Not everyone has access to them, however, and only dollars are accepted.

That night, back on our floor of the deserted hotel, we lined up shoulder to shoulder in front of the elevators and demonstrated our best North Korean goose step march while one of the guys took a photo. The shutter clicked, we burst into laughter, and the elevator doors slid open to reveal the head of the DPRK government tourist service. A couple seconds earlier and he would have walked straight into our goose-stepping line.

He was friendly enough to talk to, but there was something strange about his eyes. A barely submerged cruelty, perhaps. I got the feeling that he would have shipped us off to a concentration camp without the slightest hesitation.

This latest close call finally convinced us that we were losing all sense of caution. It was definitely time to leave.

Having made this trip nearly 15 years after you did, I am simply flabbergasted as to the similarities of the program, the comments, the restrictions, the so-called granted requests, etc Thank you so much! Time and life seem frozen in the DPRK. I wonder if there will ever be a “big thaw”; anything like the 1989 fall of the wall event. Greetings from a soulmate traveler. ET

Hi Elizabeth,

I’ve been following DPRK pretty closely since my trip in 2001. I’m not surprised to see them stick to the safe pattern they’ve established. They know the big selling point for foreigners is just getting in there in the first place. And they know they’ll pay. It’s a nice opportunity to grab some hard currency while dishing out a little propaganda.

North Korea will never experience the sort of thaw we saw with the former Soviet block, IMO. We’ll only see change there when the regime collapses entirely. And I’m afraid that process will cause even more misery to the poor people enduring the criminal Kim regime. There’s no way they can modernize or open up while living a privileged life on the back of a starving population.

Unfortunately, collapse is likely a long way off. One of the biggest – if not the biggest – supporters propping up the regime in the form of food aid is the US. China, Russia, South Korea and the US are all afraid of a collapse and want to stave that off, because no one has a plan for the terrible refugee crisis that would ensue.

Those are my impressions anyway, as a distant North Korea watcher. I hope you had a great trip. It’s such a fascinating place. There have been a lot of new books and films published about DPRK since my visit, including many by Koreans who escaped. Some are well worth searching out.