Of all the places I traveled in Southeast Asia, I liked Burma the best.

It was by far the most traditional country in the region. It was free of Thailand’s 7-11’s, paved roads and fast food. Free of Vietnam’s scams. And it lacked that uncomfortable undercurrent of violence and broken psyches that seemed to blight Cambodia.

Burmese people were quiet and kind. Old men in the highlands lamented the fact that young people had begun wearing pants in Rangoon, but I never once saw a pair of jeans, only the traditional wraparound longyi.

Burma kept its traditions because its paranoid military dictatorship shut the world out to keep the people down. They even changed the country’s name to Myanmar in an effort to hide the past and duck an accountable future. If they just pretended hard enough, would the outside world think they were someplace else?

Visiting such a country brings with it the risk that the money you spend will go towards supporting the regime. But I believe it’s a risk you must take. For many Burmese, independent travelers are their only bridge to the outside world. And their stories deserve to be heard.

I spent a month in Burma back in 2002. At that time visitors were expected to change a set amount of foreign currency — I believe it was $300 each — into “Foreign Exchange Certificates” (FEC’s) on arrival. It was illegal for Burmese to possess hard currency. And of course the FEC’s sent that money directly into the rotting pockets of the military.

The FEC policy was suspended late in 2003 and no longer exists. But at the time I went there, dodging it was a bit like stepping into a Cold War film.

The foreign exchange counter at Rangoon airport had been placed squarely in the middle of the arrivals hall, just before the customs post. It was impossible to bumble past while feigning preoccupation with your luggage. That was my first ruse and it didn’t work.

The woman at the counter shouted and waved me back. “You must change $300!” she said. “Each.”

I lowered my voice, leaned on the counter and said, “But I don’t want to change $300. Do you think you could help me out?”

She took a quick look over her shoulder at Immigration. “How much do you want to change?” she asked, leaning towards me with her voice pitched low.

“I was thinking…. $50” I said. That would be just enough for a pair of train tickets north, which had to be purchased from the government office anyway.

She took my money, counted out 50 FEC’s, stuffed them into an envelope, sealed it, and wrote “$300” on the outside. “Show this to the customs officer,” she said, licking her lips and leaving a thin coating of spittle. “And now… do you have a present for me?”

“What would you like?”

“Ten dollars!”

I burst out laughing and gave her $5.

That solved the problem of keeping as much of my hard currency as possible out of the hands of the government. But I wasn’t in the clear just yet.

Burma is subject to international sanctions, so credit cards and ATM’s wouldn’t work there. Cash is king, and I was carrying a month’s worth. But I still lacked a way to turn it into the local currency, which would enable me to put money in the hands of those who needed it most.

FEC’s could only be spent in certain places — at government approved hotels, on taxis, and on railway, bus or boat tickets. I used mine to get a taxi into town. On the way there I consulted a guidebook for a list of official “hotels.” I wanted to avoid those because they’d be overpriced, and because that money would make its way to the bastards in power.

I still don’t know how I found the “guesthouse” where we spent that first night. It was a small place owned by Indian traders, on the second floor of a decrepit colonial building lost down a forgettable side street. We had to trudge up a dark stairway full of auto parts and then walk through some sort of machine shop to get to the door. I bargained for a tidy little room with a shower, and told the owner I’d pay him as soon as I got my hands on some cash.

“How do I go about getting money anyway? Can you change it for me?”

“Oh no!” he said. “That’s illegal.” And then he leaned closer. “Just go for a walk. Someone will find you.”

My girlfriend and I dumped our packs in the room and took a stroll through old Rangoon. Sure enough, we’d only made it halfway down the first block of old colonial buildings, their white facades faded to the colour of limburger cheese, when a man slid up beside me.

“Change money?” he whispered from the corner of his mouth.

I looked him over quickly. “Yeah, okay.”

“How much you want to change?”

“A hundred.”

“Big head or small head?”

That made no sense at all until I realized he was talking about the bills. Was it a new US hundred — the big head president — or an old one? They got different rates on the black market.

“Big head.”

He offered me 1150 kyat to the dollar and I accepted.

“Good. Please follow me.” I moved to walk alongside, but he held out his arm and barred my way. “Stay a bit back.”

The man walked half a block ahead, taking several turns and sometimes doubling back. He never once turned around to make sure we were there. I kept him in sight but maintained that same distance. Eventually he walked into a small tea shop on a side street. I looked around and followed him in.

“Please sit,” he said, gesturing to a nearby table and ordering coffee for the three of us. “Now, show me the money you wish to change.”

I slipped a hand into my pocket, palmed the hundred dollar bill and showed it to him. His eyes widened slightly, and he darted a quick look around.

“Okay, wait here.”

He got up and ducked out the door. I wondered briefly if it was a trap, then went back to sipping my coffee. Either way, it’d be interesting to see how it played out.

Five minutes later he was back, followed by another man who looked colder and more businesslike. This was obviously the one who carried the cash.

We went through the routine of me showing them the hundred dollar bill in my palm again. The new man was satisfied. He reached into his shirt and took out a large roll of kyat, made a show of counting it, and then passed it to me under the table. I began counting it carefully in my lap.

“Give me your hundred,” the original man said. “I can hold it for you while you count.”

I shook my head and kept counting. They kept looking over their shoulders and making gestures to leave.

As I expected, their stack was a bit short. I tossed the pile onto the table in front of the second man. “That isn’t right,” I said, pushing back my chair and moving to stand up.

“Okay, okay,” he said, covering the cash in a panic and gesturing for me to sit down. He added several bills to the roll without looking — he’d obviously slipped them aside intentionally — and passed it to me under the table again.

I took my time, counting it all once more from the beginning. This time it was correct. I shoved the entire roll into the waistband of my pants and passed him my hundred under the table. Both men got immediately to their feet and rushed out the door, turning down the street in opposite directions.

“I guess that’s our cue to leave,” I said. We downed our coffees and struck a casual pace to a busier street, losing ourselves in the crowd.

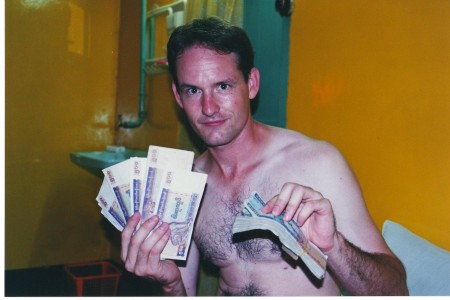

Back in our room, I realized that the stack of kyat was so large I’d have to carry it in a plastic bag shoved into the bottom of my backpack. I don’t think I’d ever held such a large pile of cash before. And so I did what any self respecting traveler would do. I spread it out on the bed and I rolled in it.

Cash is King…cash is king…

Thank you Ryan…that was splendid! I enjoyed it very much; you are a most excellent writer with a wonderful style..LR

Thnx Laney, glad ya liked it 🙂