I’m just back from a short trip to Northern Greece.

Thanks to this seemingly endless pandemic, I hadn’t left Berlin since last summer’s hiking in the Slovakian High Tatras. In fact, I only left my neighbourhood twice since I moved to a new flat at the start of December.

It was strange to be on the road again — and strangely tiring after nearly two years of introverted lockdown routine.

I discovered pure gold in the hinterlands around Thessaloniki. Unfortunately, I couldn’t bring it home.

I’m talking, of course, about the burial horde of the kings of Macedon, those seemingly unstoppable warriors who descended from their Balkan homeland to unify a warring Greece.

The city-states were bogged down in disputes between temporarily allied rival factions when Phillip II of Macedon came on the scene in 360 BC.

He thumped his nearest enemies — the Paionians, Illyrians and Thracians — while testing and perfecting new siege machinery and catapults, and new infantry tactics. And then he turned his attention to the squabbling south.

By the time of the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Phillip was the undisputed ruler of Greece.

Unfortunately, his triumph would be short lived.

The Macedon king was assassinated in 336 BC, and succeeded by his son Alexander, soon to be known as The Great.

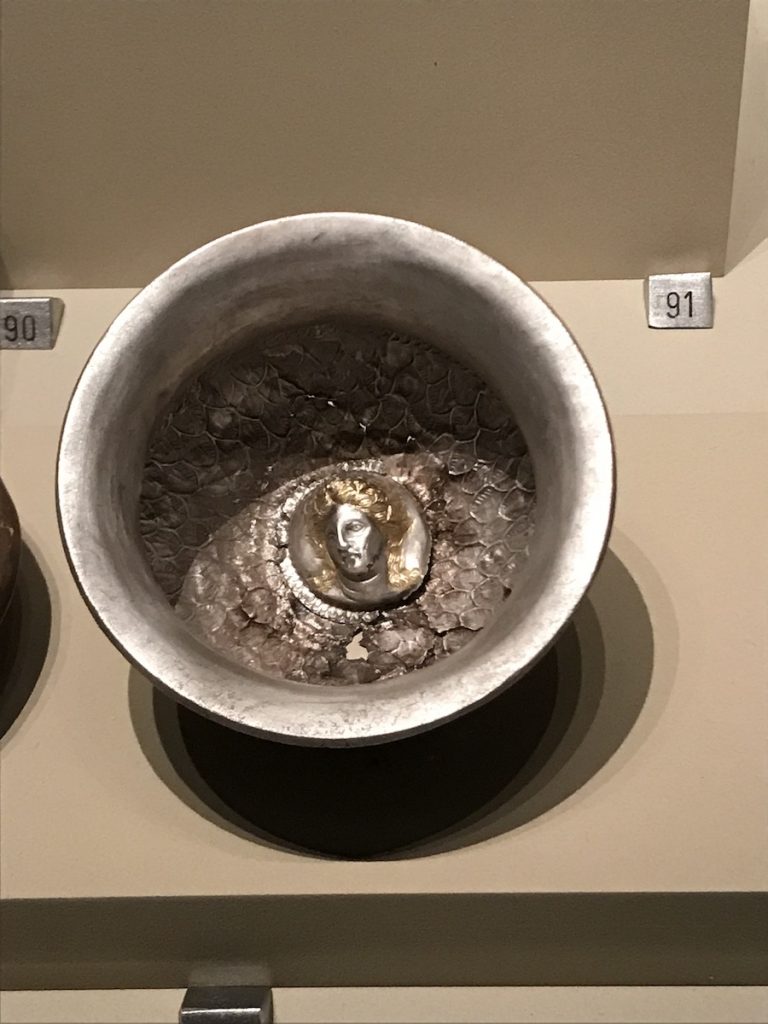

Alexander held a lavish funeral for his father, committing the old man to the earth with a wealth of grave goods that included several complete sets of armour, weaponry, an ivory couch, drinking vessels, and more gold than you could shake a smelter at.

His duty done, Alexander didn’t want to hang around long enough to marry and sire an heir. He was plagued by the feeling his time was short, and he had serious campaigning to do.

After performing sacrifices to Zeus at Dion — more on that in an upcoming blog — Alex crossed the Hellespont and set out to conquer the known world. He made it as far as India but died of fever on his way back, breathing his last in Babylon in 323 BC. He was just thirty-three years old.

Alexander’s squabbling generals divvied up the lands he’d subdued, and for a while, Hellenic rule continued. But the rise of Rome wasn’t far off.

Anyway, we were talking about Philip II.

Digging had been done at Vergina, about an hour west of the northern capital of Thessaloniki, since the late 1970s, and by greedy grave robbers in the centuries before that. Many partially-looted tombs had been discovered, but one particular burial mound would stun the region’s archaeologists into awestruck silence.

It was in late 1977 that Professor Manolis Andronikos found an unlooted Macedonian tomb beneath a massive earthen tumulus 100 metres high and some 12 metres wide.

The scientists scraped away 60,000 cubic metres of soil, until they uncovered the sealed door of a two-room vaulted chamber filled with grave goods.

Phillip II’s cremated remains were interred in a golden box, topped with an intricately woven golden diadem in the shape of a wreath.

The bones revealed evidence of a crippling leg wound, one that matched an injury Philip II is known to have received.

Fifty of the fifty-one tombs here had been robbed, but not this one. This was indeed the ancient Macedonian city of Aegae, and it was here that Philip II was killed by Pausanias of Orestis, a member of his personal bodyguard.

He’d gone there to attend a wedding.

Fascinating. Love the stories. I should’ve been an archeologist as I enjoy these discoveries. Thanks for sharing. You are a good writer.

Thanks Clark, glad you enjoyed it. That was such an interesting place. The collection of artifacts rivalled the much larger antiquities museum in Thessaloniki.

I’d hoped to get to the ruins of Pella (ancient capital of Macedon and Alexander’s birthplace), and to Philippi (where Octavian and Mark Antony caught up with Caesar’s assassins), but the trip was too short and they were too far afield. I do have one more interesting ancient site to share, will post that next week. Bogged down with column deadlines today.