I’m moving flats soon, after four years, leaving this neighbourhood behind for another pre-war altbau in a different part of the city.

Imminent departure has prompted me to poke around some of those minor historic sites I’ve passed so often but never gotten around to exploring.

One of the largest is just down the block.

I biked past that strange concrete mass so many times over the past four years on my way to and from the gym.

It’s a remnant of the Nazi era, and one of the few surviving traces of Hitler and his architect Albert Speer’s megalomanic dreams.

The so-called Heavy Load-Bearing Body (Schwerbelastungskörper) wasn’t meant to be seen. It would be buried as the ground around it was raised for the monumental buildings that would come later. This huge lump of concrete would simply pave the way.

No one knew what it was for years. Could it be the remains of a bunker or a water tower? There are still plenty of bunkers left in Berlin.

It was only when the plans were discovered that historians realized this thing was part of Germania, Hitler’s delusion of a re-made capital for his Thousand Year Reich.

Otto Friedrich wrote in Before the Deluge, “Adolf Hitler never liked Berlin. He disliked its wit and its cynicism and its cosmopolitan atmosphere.”

He meant to remake this city he loathed into the monumental capital of a new totalitarian Europe, with the massive Hall of the People (Volkshalle) — it would be the world’s largest building (capacity 180,000) — near where the Reichstag stands today. The oculus of its dome would have accommodated the entire rotunda of Hadrian’s Pantheon in Rome, and the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica.

What would the people do in their hall? No doubt sit there and listen to the Fürher’s endless rants.

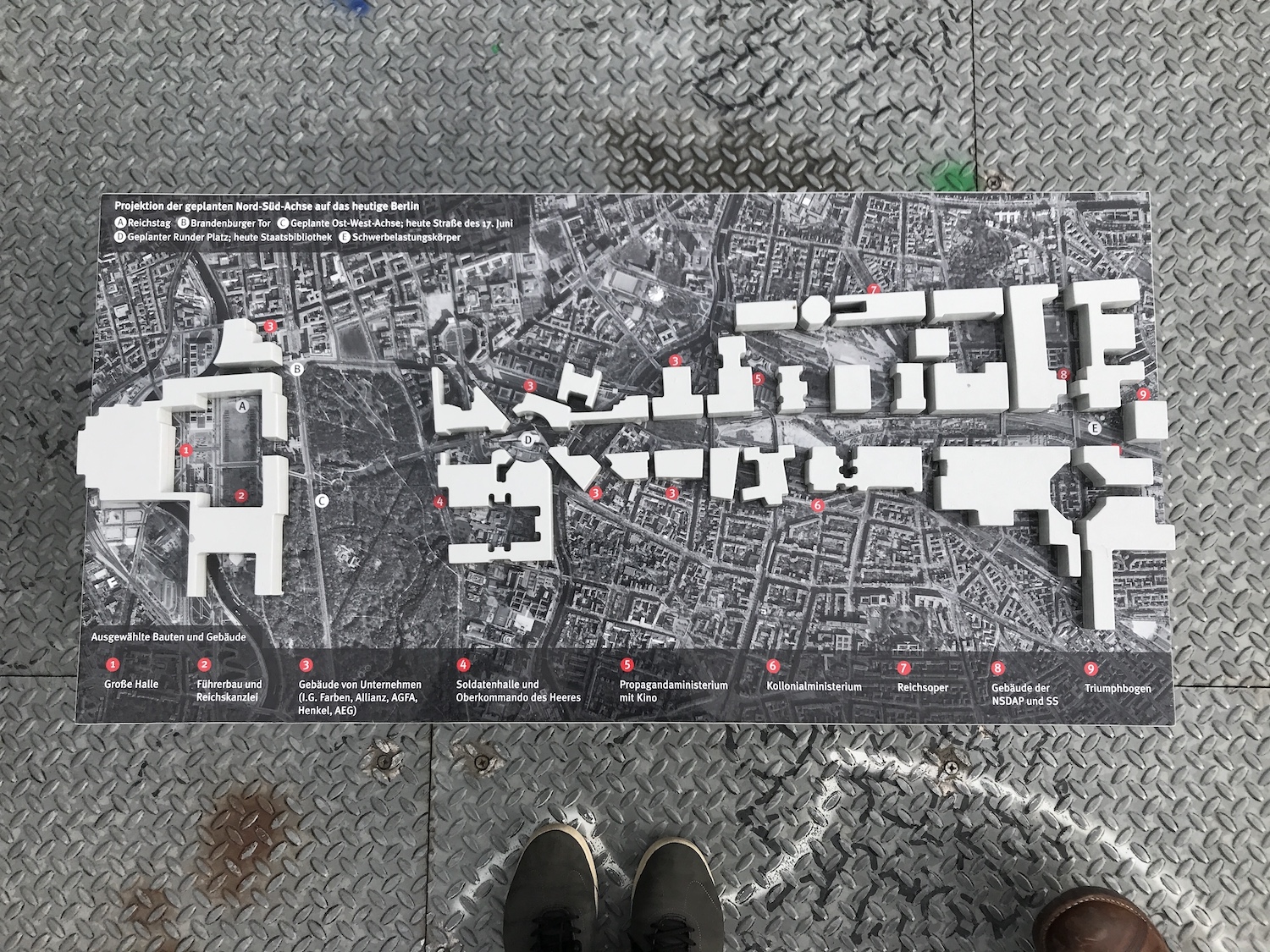

Germania would be built on two vast axes. The east-west axis passed through Brandenburg Gate and the Tiergarten. The north-south axis would pass through today’s government quarter, with the Hall of the People on one end, and a massive 117-metre high triumphal arch on the other.

That arch would have towered over my current flat. In fact, its dimensions would have massively exceeded any existing structure in Berlin. They had planned to build it just down the street.

I suppose “planned” is an optimistic word. Too optimistic for their creepy delusions. When he saw the scale model of Germania, Speer’s father reportedly said, “You have completely taken leave of your senses.”

I’ve seen one of the last remaining scale models, too, and I have to agree with Old Man Speer.

But we were talking about that colossal hunk of concrete down the street.

The Heavy-Load Bearing Pillar was built in 1941. French forced labourers were used in its construction.

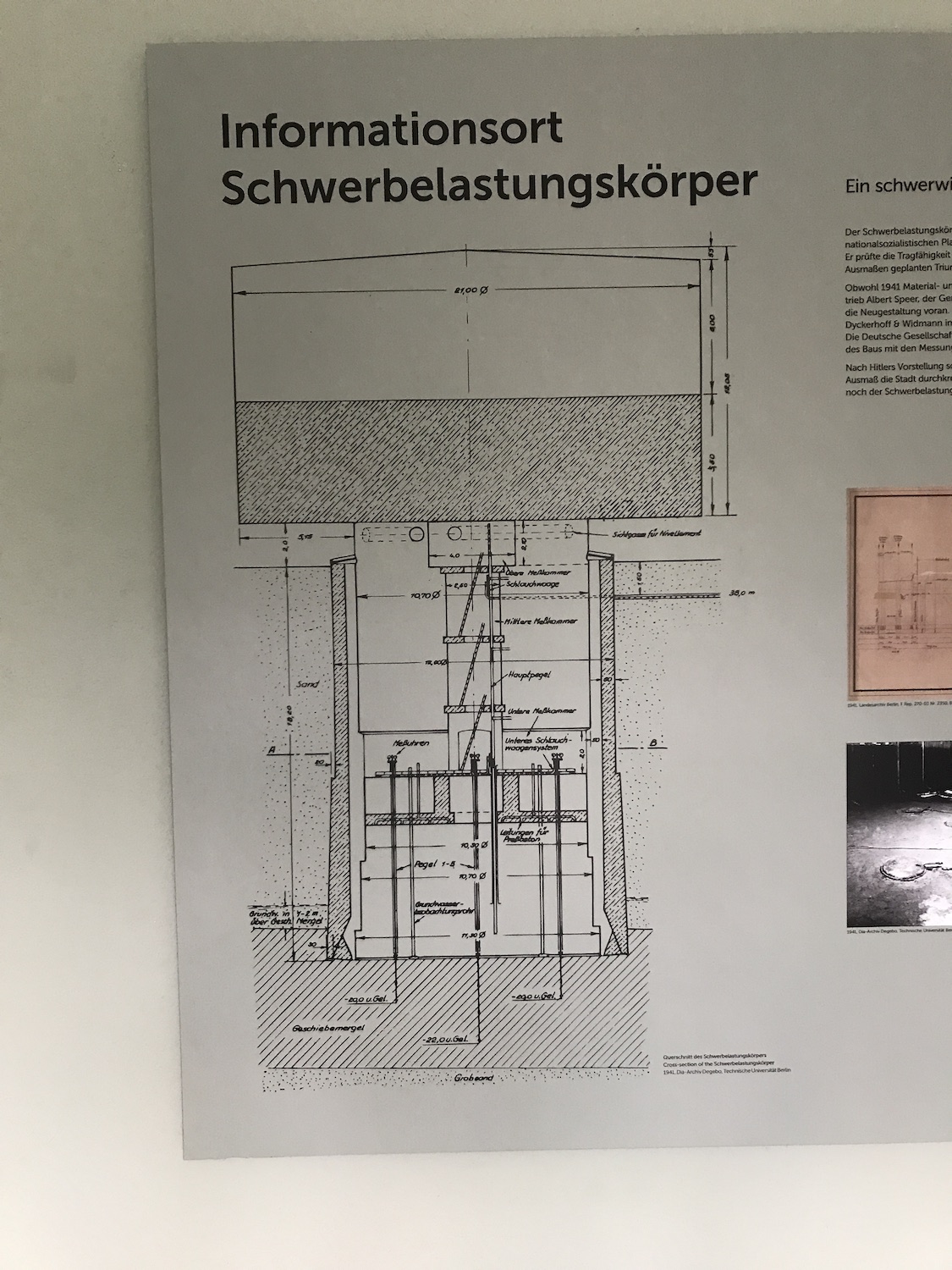

The technical-minded reader will be interested to know that it is 21m in diameter, and 14m high — but it extends a further 18m below the ground. If you go inside, to the small instrument room beneath the solid concrete cap, you can see ladders descending three storeys into the earth, to where the gauges must have been, or whatever they used to measure the results of this experiment.

You see, Berlin is built on sandy ground, with a very shallow water table. Parts of the original city were marsh. The ground in my neighbourhood is also partly clay, and so it was difficult to calculate the weight of the massive arch they meant to erect here. How embarrassing if it would have tipped over, like their horrid hopes and dreams.

The 12,650 ton concrete cylinder was put there to test the ground, to see if it could support the weight of the planned building. The cylinder was roughly the same weight as one pillar of the planned arch would have been.

If it sank less than 6cm, the soil would be deemed good enough for construction without additional stabilization. It sank 19cm in two and a half years.

The ground would have been raised to the height of the cylinder — 14 metres — for that 120 metre wide 7km long north-south axis, and the heavy load-bearing pillar would have been buried beneath it. But World War Two intervened, and put an end to Nazi madness.

It was impossible to demolish the massive concrete structure; there were too many buildings nearby to blow it up safely, and so it was left as a reminder of the monstrous plans that Hitler and Speer had for this site.

The German Society for Soil Mechanics continued to perform measurements in the pressure chamber until 1983. It was abandoned for a decade, until it was listed as a historic building in 1995.

Today it sits amidst a patch of trees and tangled greenery, across the road from Lidl, and next to the S-bahn line from Oranienburg to Wannsee. Just another layer of the past in this neighbourhood that we walk by without a second glance.

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...