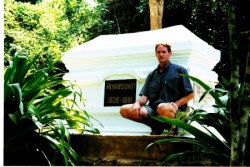

Sunlight slants through verdant jungle and illuminates a simple white painted tomb on a hillside overlooking the Nam Khan River. Someone has hacked back the growth to open a view of the smooth brown waters, but vines are encroaching yet again. A square brass plaque, tarnished by constant moisture, reads simply “Henri Mouhot 1826-1861”.

Sunlight slants through verdant jungle and illuminates a simple white painted tomb on a hillside overlooking the Nam Khan River. Someone has hacked back the growth to open a view of the smooth brown waters, but vines are encroaching yet again. A square brass plaque, tarnished by constant moisture, reads simply “Henri Mouhot 1826-1861”.

Mouhot is credited with “re-discovering” the ruins of Angkor Wat and with popularizing them in the West. His 1858 to 1860 expedition, chronicled in Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos, ended with his death at age 35. In that very same spot on the riverbank 7km outside of Luang Prabang, Laos, he scratched out his final fever-ravaged journal entry: “Have pity on me, oh my God!”

Mouhot’s grave was lost to the jungle until its accidental rediscovery by foreign aid workers in 1990. Today it’s a quiet place, protected by birdsong. The river gurgles gently as it nears communion with the mighty Mekong. I sat there on the edge of the tomb in light tinged with the green of undersea, and I thought about what it takes to be an explorer.

It is the fate of explorers to leave their bones in lonely places, forgotten except by others of their kind. They forsake a comfortable home and contact with family for the coarse life of the camp. They embrace disease, pestilence, and the hazard of violence for what many would consider scant rewards.

It is the fate of explorers to leave their bones in lonely places, forgotten except by others of their kind. They forsake a comfortable home and contact with family for the coarse life of the camp. They embrace disease, pestilence, and the hazard of violence for what many would consider scant rewards.

What unstoppable urge sparks the drive to take such risks and to endure such suffering? For Mouhot it was simple. He took joy in the process. His journals record his pride in the great number of new species he had collected. He wrote, “[…] even if destined here to meet my death, I would not change my lot for all the joys and pleasures of the civilized world.”

Others seem driven by ego, by the need to prove something to themselves or to the world. And for some it’s the quest for scientific knowledge. For me the driver has always been curiosity, a burning need to see what’s around the next bend, an all-consuming desire to understand, to feel, and to see it for myself. That and a child’s sense of adventure, I think.

Some say the great Age of Exploration died with Wilfred Thesiger. I disagree. It has simply changed. New eras are upon us. People like Sir Ranulph Fiennes, who the Guinness Book dubbed “The world’s greatest living explorer”, continue to test the limits of human endurance. Robert Ballard pushes into new and unsuspected ocean frontiers, while Johan Reinhard probes the hidden reaches of our past — for the hidden past truly is a lost world, and time is imaginary.

Some say the great Age of Exploration died with Wilfred Thesiger. I disagree. It has simply changed. New eras are upon us. People like Sir Ranulph Fiennes, who the Guinness Book dubbed “The world’s greatest living explorer”, continue to test the limits of human endurance. Robert Ballard pushes into new and unsuspected ocean frontiers, while Johan Reinhard probes the hidden reaches of our past — for the hidden past truly is a lost world, and time is imaginary.

As technology evolves we sit on the cusp of new journeys outside the confines of our home planet, into our solar system and possibly beyond. Will future students read about the exploits of planetary explorers with the same sense of wonder and envy that I read of Sir Richard Francis Burton? And will your descendants be among them, sailing bravely away to the unknown stars?

Nice, Mr. Ryan. Curiosity is the key to an engaged life. And what worth is life if it is lived passively? Keep up the inspired writing!

hello,

coach murdock, you raise an interesting set of questions about the future.

interesting that future explorations will be performed by those rooted in searching for the past.

thanks