In the Black Hills of South Dakota, not far from the patriotic visage of Mount Rushmore, the curious traveler can find the growing realization of one man’s dream.

In 1939 Chief Henry Standing Bear of the Sioux asked Bostonian Korczak Ziolkowski, already a well-known sculptor, to come west to carve a mountain. Standing Bear wanted him to tell the story of his people, “So that the white man will know that the red man has great heroes also.”

Korczak accepted that invitation seven years later, upon return from military service in WWII. He knew the story of the North American Indian was an epic that could only be told on an epic scale. He decided to carve the entire mountain, rather than just the top 100 feet as had been originally discussed. Further, he would carve it in the round — in three dimensions. That decision shaped the rest of his life.

The Crazy Horse Memorial will be the largest sculptural work the world has ever known. When completed it will measure 563 feet high and 641 feet long. All four heads of Mt Rushmore will fit into Crazy Horse’s head, with room to spare.

It was obvious to Korczak that a project of such colossal ambition would never be finished in his lifetime. Skeptics derided him as a dreamer and a madman; they didn’t think it could be done at all.

It was obvious to Korczak that a project of such colossal ambition would never be finished in his lifetime. Skeptics derided him as a dreamer and a madman; they didn’t think it could be done at all.

Korczak wanted more than just a famous statue. “I’m not interested in a tourist gimmick,” he said. He intended to tell the story of the Indian by preserving examples of Indian cultural heritage, the growing collection of which is now displayed onsite in the Indian Museum of North America. His legacy to future generations would be the creation of a formal educational institute and medical center. None of it would be publicly funded. Korczak believed that, to be meaningful, the entire plan must be funded privately, from the donations of visitors.

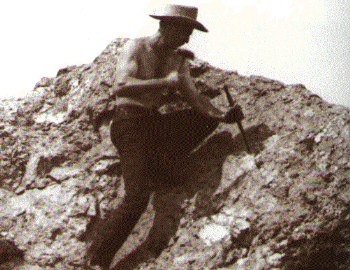

He started the project in 1947, living in a tent at the base of the mountain with $174 dollars to his name. Over the years he twice turned down $10 million dollars in potential federal funding. Sixty years later the project is still going strong, funded only by those who believe in it.

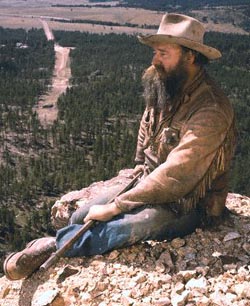

In many ways Korczak was a man born after his time. Or perhaps better to say that our present time was too small for him. Such a selfless vision died out with the great cathedrals of the middle ages. Or perhaps it is we who have changed. Crazy Horse is a dream too big for the hand of one man; it will take generations, a family.

It was a project that seven of Korczak’s ten children and several of his 23 grandchildren would take up at some point in their lives. Ruth, Korczak’s wife and lifelong companion, continues to direct the project and still lives at the site. She’s been there since 1947 and has been the driving force of the Crazy Horse Monument since Korczak’s death in 1982.

“The blackest mark on the escutcheon of the American people is the story of the Indian,” Korczak said. “I’d like to think that our country is great. I’d like to think that we are capable of righting a wrong. This is my purpose. I want to right a little bit of the wrong that we did to these people.”

“The blackest mark on the escutcheon of the American people is the story of the Indian,” Korczak said. “I’d like to think that our country is great. I’d like to think that we are capable of righting a wrong. This is my purpose. I want to right a little bit of the wrong that we did to these people.”

Crazy Horse has become much more than even Korczak’s grand vision. It has become a testament to human perseverance, to dreaming great dreams. We need that in an age when our ambitions are so small and so personal, when success is a matter of purchasing power.

Find out more about the Crazy Horse Memorial by visiting www.crazyhorsememorial.org