This is the thirteenth in a multi-part blog on North Korea. You can find the others here

Every first world metropolis needs a subway, and the Great Leader’s urban paradise is no different. But as with everything else, the North Koreans went a little overboard. Other world cities pride themselves on having functional transportation systems. Pyongyang’s exists as yet another monument to the glorification of the Fatherland.

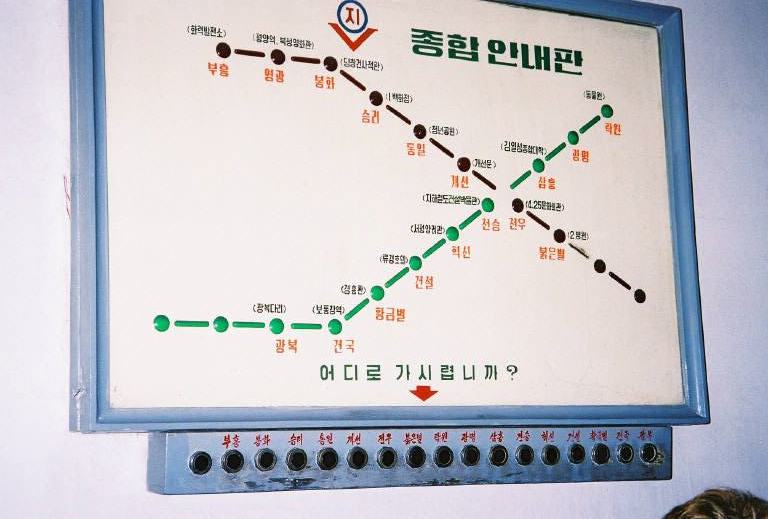

Each subway station in Pyongyang is slightly different, with a different décor and name derived from its revolutionary theme, which bears absolutely no relation to the station’s geographical location.

The stations I visited were deep underground, far deeper than necessary judging by the flat topography of the city and the lack of competing lines. The escalator felt like it was descending to the Earth’s core, or perhaps to the depths of hell. My ears popped more than once on the way down. I assumed the stations were to be used as bomb shelters in the event of war, or that they had some other nefarious purpose.

I’ve largely confined these travelers’ tales to what I saw and heard at the time, rather than bring in what I learned after I got out. But I’ll make an exception here. I later learned that our suspicions were likely quite accurate. This quote from a very cool website on the Pyongyang metro: “Documents passed to Changchun Car Company, which built the original subway cars, indicate that Pyongyang has a substantial secret metro system for government use“, and “Apart from the secret lines, the Pyongyang Metro was designed as part of a broader military system of tunnels and underground installations. The stations are very deep underground and are fitted with multiple (usually triple) heavy blast doors, indirect linking tunnels, and other features that imply military purposes or service as emergency shelters.” I’ve provided the link at the bottom of this blog for anyone interested in reading more.

The platform of Puhung (Rehabilitation) station was built of marble, polished to a high sheen to better reflect the glow of the enormous chandeliers which lit the station. Its walls were adorned with broad ceramic tile mosaics, the largest of which graced the entryway above the stairs: “The Great Leader Comrade Kim Il Sung among Workers” (15.8 x 9.25 m). According to the official English-language brochure The Pyongyang Metro: “In the underground station is the mosaic mural “The Great Leader Kim Il Sung among Workers” which depicts the great leader who, regarding “The people are my God” as his motto, devoted his whole life to the people, sharing life and death, sweets and bitters with them.”

Here’s another dose, if you simply can’t get enough of that wonderful propaganda: “The works of art at Puhung Station represent the appearance of the country which is prospering day by day and the happiness of the working people who enjoy the equitable and worthwhile creative life to their hearts’ content thanks to the popular policy of the Workers’ Party of Korea and the Government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.”

Despite the questionable choice of subject matter, the North Koreans really do excel at this type of art. Their craftsmanship is impeccable. By contrast, the subway cars themselves were a little down at heels. The doors didn’t even open automatically–we had to open them manually, and turn to slide them shut again. Inside each car the two regulation framed portraits of the Leaders hung at one end, in case we needed another reminder of who’s in charge, or who we have to thank for all this.

Our car was nearly empty, perhaps because they’d chosen the national holiday to take us for our token ride, or perhaps, as I suspected, because the system rarely ran, given the power cuts and blackouts which have become a daily constant in the country. Quoting again from the Pyongyang Metro website: “Indeed, whether the Metro is in regular service at all is not entirely certain. Practically the only non-North Korean eyewitnesses to Metro use are the visitors given the showcase ride on the system.”

It seems that the other passengers in our car may have planted there for our benefit, though they did do a very good job of seeming to be surprised by the presence of foreigners: “Inevitably, they are taken for a one-station ride, between Puhung and Yonggwang stations, accompanied by their North Korean guides. A handful of well-dressed Korean passengers also board the train.”

Our driver was already waiting for us when we arrived at the next stop: Yonggwang (Glory).

After touring the subway station, we were whisked off to an amusement park. This wasn’t part of the official agenda; it was actually a request. It all came about as we drove past the park on our bus a couple days earlier. One of the guys in our group saw the park, leaped to the window, and in a thick Norwegian accent cried with great sincerity, “Oh a roller coaster! Why are we just going past?” Being rather compassionate individuals and quick to extend the hand of hospitality, our minders sought permission to take us to this gem of the People’s Paradise.

At first glance, the Mangyongdae Fun Fair didn’t look like very much fun. It was shabby and down at heels, a far cry from Disneyland or even Canada’s Wonderland. Glum soldiers with Kalashnikovs guarded the entrance—perhaps to ensure patrons really did have a good time. Many of the “rides” seemed like the rusted remnants of an inner city children’s park.

The only notable attraction was the roller coaster we had spotted from the road, but even it looked exhausted. Ground down by privation and years of hardship, it seemed barely able to summon the inertia to make it around its two loops. Every time I watched it go up, I was sure it would creep to the top, lose speed, and simply fall off.

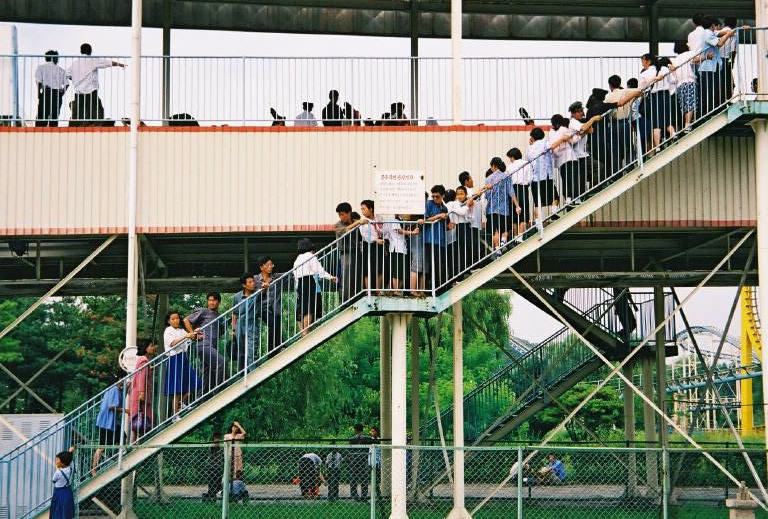

A few of us agreed to ride it with Jon, despite the fact that we had to pay $4 each. A long line of Koreans snaked around the platform’s base; they’d probably been waiting for two hours or more in the stifling summer heat. One of our minders simply pushed through to the bottom of the stairs, barked a command, and everyone immediately cowered aside to let us pass. I didn’t see a singe person grumble at the unfairness of our VIP treatment.

Now I have to tell you that I’ve jumped out of airplanes, climbed mountains and met grizzly bears in the wild face to face. I’m not the least bit nervous about roller coasters because they’re designed to be safe—but this one looked like an elaborately devised random execution machine, something straight out of Kafka. It was with considerable hesitation that I allowed them to strap me in.

The cars creaked and groaned as they slammed around the track, metal screeching against metal in a triumph of communist engineering. When we reached the top of the loops, I did feel that moment of indeterminate hesitation I saw from below, but after only the briefest of shudders we continued down the other side, shaken and thankful to escape with our lives. The entire ride—one circuit of the tiny track—lasted less than a minute. Not really worth the wait for all those Korean people, but I guess it was worth $4 to us because it was so odd.