This is the sixteenth in a multi-part blog on North Korea. You can find the others here

Our presence on the wrong side of the frontier caused a mild scramble among the South Korean forces.

Frantic radio messages were dispatched. Binoculars were trained on us. Reinforcements jogged over to take up positions half-concealed by the corners of buildings, where they conducted a whispered conference and pointed accusing fingers of guilt. They clearly considered us traitors to humanity.

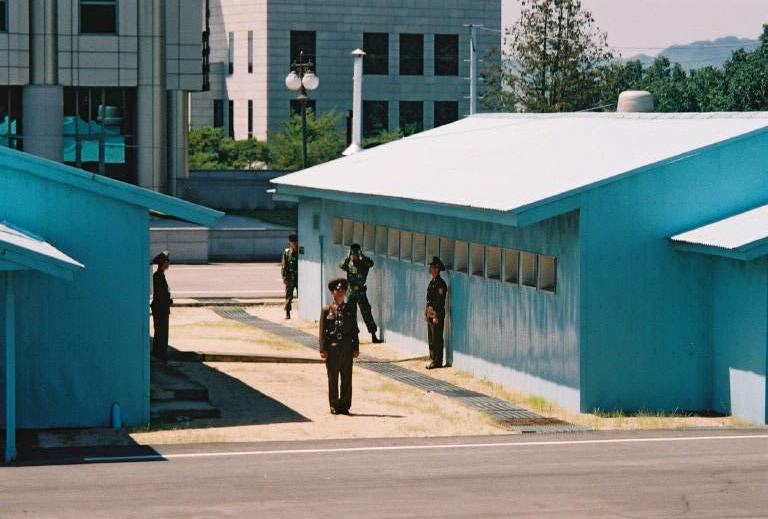

A group of North Korean soldiers– the promised “escort for our protection”–was posted at attention along the edge of the line, and a pair flanked the freshly painted blue door of the truce building.

Our escort whisked us directly inside, where a table had been divided precisely down the middle by the 38th parallel. Having experienced the North Korean sense of one-upmanship, I could just imagine the petty squabbling which must take place there, each side attempting to grab just a little more territory by pulling the table towards them when they thought no one was looking.

Like their North Korean counterparts, the US military also conducts tours on the South Korean side of the DMZ, and a strict agreement is in place to prevent brawls inside the negotiating room–when one side enters, those from the opposing side are not allowed to go in.

For guests of the US Forces, walking to the opposite side of that room–and technically crossing the line–is as close as most people will ever come to entering the world’s most reclusive country. I guess it was fitting that, on a trip where everything felt like a strangely reversed mirror image of reality, I had the opposite experience–it’s the only time I’ve ever stepped over the border to enter the geographic territory of South Korea.

I’ve spoken to friends who participated in those US military tours, and I’m told it’s a serious, strictly supervised affair overburdened with a list of strange rules: dress codes are enforced, with collared shirts, no jeans, no open-toed shoes, and no clothing featuring English lettering. It’s also absolutely forbidden to gesture towards, point at, or otherwise attempt to communicate with the North Korean forces on the opposite side.

The North Korean tour was nothing like that. Instead of acting tense, the soldiers inside the truce building went out of their way to seem laid back and sociable. They laughed loudly at our jokes, answered all our questions, and smiled as much as possible. They even encouraged me to lean back comfortably in my chair and put my feet up on the conference table. They really went that extra mile to present the impression that we were all one big happy Juche-believing family.

Even as we sat there laughing it up, the South Korean military was busy adding to our dossier. South Korean soldiers stuck their faces right up against the window glass, staring at us intently while speaking into portable radios. They peered at us through binoculars to see us better from 5 feet away, and one arrived with a camera and attempted to capture a clear photo of each of our faces.

Unlike the US military tour guides, the North Koreans didn’t discourage us from making attempts to communicate. They pointed at the enemy soldiers and laughed as though to say, “See what we’re up against?” When I finally had enough of all the picture taking, I pulled out my camera to take photos of them taking photos of us. The North Koreans just laughed and encouraged me.

Back outside, the air was thick with heightened tension. South Korean soldiers had taken up positions that mirrored those of our escort, standing eye to eye across that thin concrete line, glaring into each others faces only centimeters apart. I was reminded of the fact that, despite all the rules, gunfights sometimes broke out here.

Back outside, the air was thick with heightened tension. South Korean soldiers had taken up positions that mirrored those of our escort, standing eye to eye across that thin concrete line, glaring into each others faces only centimeters apart. I was reminded of the fact that, despite all the rules, gunfights sometimes broke out here.

I still couldn’t believe the world’s most heavily defended border was nothing more than a strip of concrete one foot wide and a couple inches high, with only self-discipline separating hate from fanatical hate.

I turned to our escort. “What would happen if one of us tried to run across the line?”

“You’ll be shot,” he said.

That was ambiguous.

“Who’ll shoot us?” I asked. “You guys or them?”

“You’ll be shot,” he repeated, looking me steadily in the eye. It was pretty clear which side he was referring to.

By then an American soldier had joined the South Korean deployment. He lingered in the background, watching us from around the corner of a building while the South Koreans continued to photograph us, one man using binoculars to spot and direct the man with the camera.

I turned my back and put my head down anytime I saw that camera being raised, but in the end it wouldn’t have made much difference. The video cameras that peppered the wall of the building opposite us were busy recording everything.

I resented that a little. I realize they need to watch the DMZ carefully, and that they would naturally be suspicious of someone who gained access to the other side. But the thought that some government bureau-rat might one day hold this trip against me–or even worse, attempt to label me as a sympathizer–really pissed me off. I’ll travel wherever and whenever I like. I’ll see things for myself and form my own opinion as to the conditions and rightness or wrongness of a place. I don’t need a nation or a government to tell me how or what to think.

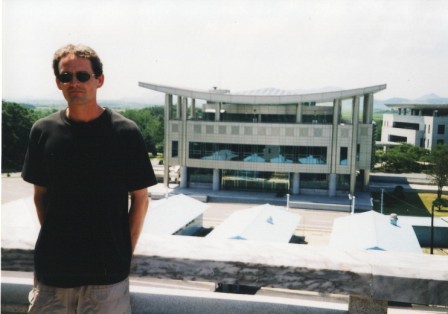

When we finally had enough of being stared at, suspected and photographed, our military escort led us inside the large glass-fronted building, to a second storey balcony overlooking the line. By the time we got there the South Korean solders on the other side had disappeared, but I’m sure they were watching us from the other large building that mirrored our own.

I was posing for pictures when one of the North Korean soldiers approached and began to interrogate me.

“What do people in your country think of North Korea?” he asked. From the sneer on his face, I knew he was itching for an argument.

“What do people in your country think of North Korea?” he asked. From the sneer on his face, I knew he was itching for an argument.

“We don’t get a lot of news from Asia,” I said, groping for a diplomatic exit. “People in Canada really don’t know very much about Korea.”

A little more honesty would have been satisfying, but total honesty would probably have gotten me shot (“Actually, the rest of the world thinks North Korea is a seething mass of brainwashed lunatics ticking slowly toward a catastrophic implosion.”)

He then said, rather forcefully, “Did you see the flag of your country on the other side?”

He was referring to a plaque on the south wall of the truce building which showed the United Nations flag, and below it the flags of each country that had fought on the UN side in the Korean War.

I admitted that I had.

“What did you think about this?”

“I was a little surprised.” It was only a partial lie. I was surprised to see a Canadian flag decorating the room, but of course I knew we’d fought against them.

“What do people in your country think about the Korean War?”

“We don’t learn much about it,” I replied. “It’s not studied much in our history classes.”

He seemed satisfied with that answer, but I knew that we each drew different meanings from my statement. He believed Canadians don’t study the Korean War because we’re filled with shame and remorse. The truth is we don’t study it because, despite the incredible sacrifices made by those involved, in the larger picture of world history it was an isolated 3 year war that happened over 50 years ago. At most it would occupy a page in a high school history textbook.

You must realize by now that the North Koreans don’t see it this way.

You must realize by now that the North Koreans don’t see it this way.

For the DPRK, the Korean War and the earlier Japanese occupation of 1925-1945 are very much current events. They’re the constant topic of films and books, newspaper stories and propaganda. They talk about it so much it feels like it happened yesterday. This obsessive resentment is deliberately kept at a slow boil by the regime. When a people are held in constant fear of the enemies surrounding them, they’re less likely to realize that the very regime which claims to be protecting them is the worst enemy of all.

While we were standing on the balcony, another soldier came over to tell us about Kim Jong-IL’s visit to Panmunjom. For the record, I don’t believe in a million years that he ever actually went there. He would never be reckless enough to place himself within an easy sniper’s shot of the Americans.

But this solider was convinced.

“When the Dear Leader was inspecting this site, a cloud of smoke came down to blanket the area. The Leader could see the DMZ, but his enemies couldn’t see him. When he left the area, the fog mysteriously lifted.”

For a moment we were knocked speechless–not by this miracle, but by the fact that the solider absolutely believed it. He, on the other hand, clearly interpreted our speechlessness as awe.

One of our guys finally managed to sputter, “Do you mean to say that the Dear Leader generates his own fog?”

The soldier simply said “Yes.”

He wasn’t smiling.