I’d only been in London for a few hours, and I was already thinking I’d have to scrap a year’s work.

We were at the British Museum, sitting one row away from Michael Palin and Sara Wheeler. The topic of their sold out talk was, “What Makes Great Travel Writing.” I’m finishing up a new book about Malta, and I expected to nod knowingly along with the speakers, patting myself on the back for a draft well polished. Instead, I was second guessing not just my manuscript, but everything I’d ever done.

Palin began by addressing the elephant in the room. “When I first started reading travel writing,” he said, “there was something vaguely shameful about it. It could usually be found down on a small shelf between erotica and gardening.”

While I’ve never thought of myself as a pornographer, there’s always been something parasitical about identifying oneself as a travel writer. The listener immediately pegs you as a shiftless sort who lives like a vagrant in five star hotels, oozing around the world on a slimy trail of freebies whilst crapping out glowing recommendations. Perhaps that’s why serious writers in the genre have preferred to say they write about place.

“But this is unfair,” he continued. “Travel writing is the most ancient form of writing. To go somewhere, into the unknown, and come back to tell others what you’ve seen.”

I turned to Tomoko. “He’s right,” I whispered, perhaps a little too loudly. “This is a noble endeavour. If I had lived three thousand years ago, I wouldn’t have been a storyteller — a fictional entertainer — but a traveler who brought back accounts of distant worlds.”

My justifications were interrupted by an irritated shush from two rows behind. I swivelled my head like an owl, honed in on the old goat who’d scolded me, and shot him a glare that would whither crops. My wife elbowed me in the ribs just as I was about to stick out my tongue.

When I turned back to the stage, Sara Wheeler was speaking about the broad scope of this flexible genre. “As long as you’ve got your structure,” she said, “you can smuggle in whatever else you want to do.”

For the writer just starting out, travel is the perfect vehicle for a story because it has a natural beginning and ending. Everything in between is up for grabs.

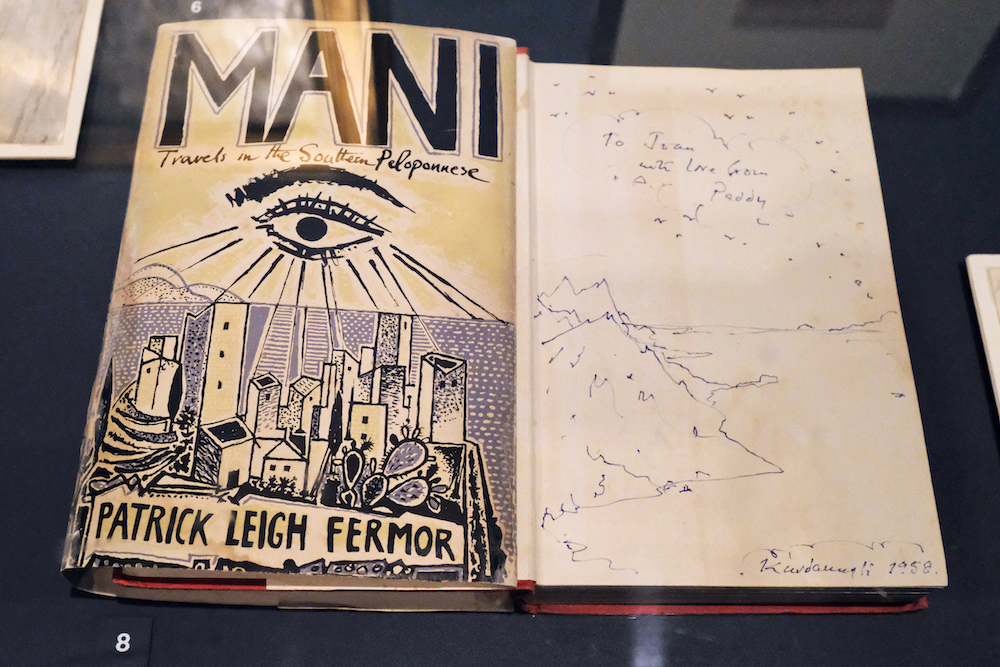

There are as many journeys as there are travelers, but there do seem to be common qualities among those we recognize as giants. Writers like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Richard Francis Burton, Robert Byron, and Lawrence Durrell were all highly resistant to authority, and they each led rather unconventional lives. They were comfortable taking on the role of the subversive outsider, abandoning the security and comforts of ordered society, casting off the restraints of time and normal responsibilities, and questioning everything. Finally, they were autodidacts, and voracious readers.

Such qualities are essential to an observant life on the road. But how do independent travelers turn great journeys into great books?

“Capture the weird and caustic characters,” Palin advised, reading a passage from Evelyn Waugh. “Let them speak through dialogue, with direct speech.”

“And remember that travel writing is not predicated on places that are hard to get to,” Wheeler added. “The poetic is in the everyday, in places like grocery stores. But it still has to be about something. I’m most interested in the inner journey.”

The critic Paul Fussell backs her up. In Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars, he writes, “Travel books are a subspecies of memoir in which the autobiographical narrative arises from the speaker’s encounter with distant or unfamiliar data.”

This is because books about journeys are also narratives of transformation. The self that set out is never the self that returns. The motivations behind each journey are also deeply personal. They can never be repeated — not on a second visit to the same place, and not by other travelers. Each of us has a personal past that we take along with us.

But as Robert MacFarlane tells us in Mountains of the Mind, you can’t write about it in a conventional way. “All good writing either works against the grain of its genre, or transcends it altogether,” he says. “Good travel writing is never just an information-gathering exercise; it must also have an emotional trajectory.”

I left the British Museum and entered a warm London night with a miasma of gloom hanging over my Malta book. We passed several inviting pubs on our way to the Hammersmith & City Line tube station, but the World Cup was on and they were too noisy. We went to Spitalfields instead.

As I sat in a generic Indian restaurant on Brick Lane, sipping a tepid pale ale, I opened my manuscript in my mind, filled its pages with angry red notes that detailed all its failings, and resigned myself to a thorough rewriting. Even after 18 years of this stuff, I had clearly learned nothing.

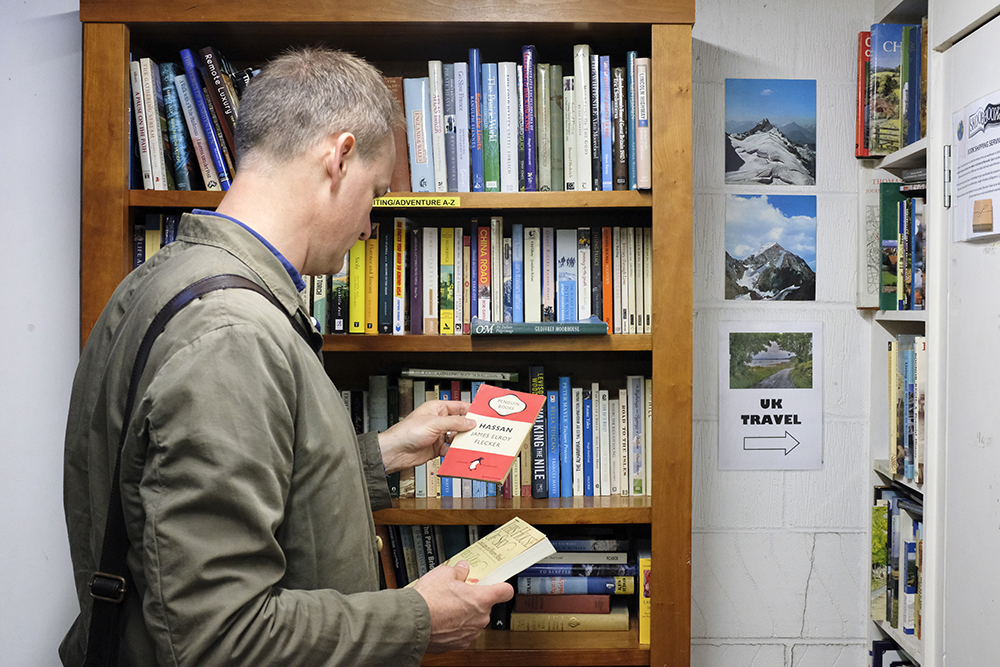

I did, however, know a lot about the genre; at least that’s what I thought. Both Palin and Wheeler had referenced Eland Books in their talk, a name that immediately evoked murmurs of approval from this well read crowd.

Eland is a legend in the world of travel literature. Founded in 1982 by John Hatt, they preserve lost classics and publish titles that capture the spirit of place. I met the current publisher, Barnaby Rogerson, for a sunny Monday morning breakfast at the Caravan cafe in Exmouth Market. If anyone is an authority on this stuff, it’s him.

Barnaby’s opening remarks immediately contradicted the sentiments expressed by Sara Wheeler two days earlier. “I’m looking for books where the traveler removes themselves from the narrative,” he said, “so the focus is on the people and the place. I think of it as anthropology-lite. It must be compulsively readable, witty, charming, and good company. But not a memoir, or a confessional.”

First memoir was in, and now it’s back out. Maybe I should focus on key writers instead?

“I’ve often thought there must be a golden age of travel writing,” I said. “A period when giants like Bruce Chatwin, Robert Byron, and Dervla Murphy walked the earth. I just don’t see anyone writing books of that calibre anymore. Am I overlooking the present by idealizing the past?”

“Good writing connects the centuries,” Barnaby replied, taking a long drink of coffee. “But we have noticed that in western writing, unless you’re dealing with exceptional souls, there is a small window of opportunity for good observational travel, between the prevailing racism of the early 20th century and the arrival of mass tourism in the 1960’s. In fact, American postwar females were some of the best travel writers. They tended to be non-colonial in their approach, and they were used to being excluded, to being both insider and outsider.”

A sip of cappuccino left me with a devilish milk moustache, and so I played the Archfiend’s advocate. “But why should anyone care about a story on India written in the 1800’s?”

Barnaby replied without hesitation. “Anyone who has read Coasting would not be surprised by Brexit. Jonathan Raban also predicted Trump in his book Old Glory. Norman Lewis predicted what would happen in Vietnam. Anyone who hasn’t read Mungo Park knows nothing of West Africa. Should I go on?”

I smiled and conceded the point. I’d read these authors, and agreed with his sentiments. It also bode well for my Malta book, assuming I could capture something essential about the island’s character.

I set the devil aside and got to the question I was most curious about. “We’re living in an age where everyone seems to go everywhere. What would you tell someone who wanted to write this stuff?”

“There aren’t enough good travel books,” Barnaby said. “There’s still plenty of scope left for great writing. But treat it like making marmalade. You’re never going to make a fortune.”

I sat in silence as he buttered his toast, collecting his thoughts by spreading the very metaphor he’d just applied to my writing.

“Stay still and get to know people well enough that you can ask them interesting questions that they are prepared to answer. Concentrate on observing a small community with anthropological intensity, but keep a novelist’s fluency in writing and the ability to construct a narrative.” He shrugged. “We find that most great travel books are formed almost by accident, by some experience that has to be written down, rather than a hungry writer looking for stories.”

By the end of all these conversations, my brain was a whirl of contradictory advice, and widely varying opinions about the details of a genre whose very nature is its incredible diversity. I needed to ground myself again within the world of my own writing if I was to get my book back on track.

I’ve always found that cemeteries are a good place to think. It’s difficult to take oneself too seriously when confronted by the brevity of life, and by the cruel hand of time. We were staying in London’s west end, so I sought out the final resting place of one of my travel heroes, Sir Richard Francis Burton.

One of the most prolific adventurers of all time, Burton lived a life people today would hardly find believable. He spoke some 29 languages and dialects. He was the first European to enter the Ethiopian city of Harare, and was co-discoverer of the source of the Nile. Burton also translated the Kama Sutra when Victorian moralists would rather have seen it repressed. His writings provide a fascinating glimpse into an age when we still hadn’t come to grips with the limits of our known world.

A christening was in progress when we arrived, or a wedding, or something involving large numbers of children and people dressed in suits. We slipped down the alley to the cemetery behind St. Mary Magdalene Roman Catholic Church, where the explorer is buried in a large stone mausoleum built in the shape of a Bedouin tent. I had been there 10 years before, and I knew there was a metal ladder bolted to the back, with a square window that has Mortlake’s best view of eternity.

The explorer’s heavy metal casket rests on lion’s paws. There is a wreath on the wall, brittle and cracked, and an old ammunition box, and flowers, and on the floor opposite the sealed entrance, a cluster of lanterns. Everything is covered in the dust of the grave. Burton died in Trieste in 1890, and his wife’s body joined his in 1896, but his journeys live on. His books are still read today.

Hymns seeped out through the thick walls and stained glass behind us as planes to Heathrow passed overhead, with engines idling, lowering their flaps for the landing run. I wonder if they knew they were passing over the grave of one of our greatest travelers?

As I sat on the grass next to his tomb, I reflected on his life, and how he had always gone his own way. I was reminded of a verse from The Kasidah, said by Burton to be a translation of an original Persian text, but written by Burton himself. In it, the great explorer reminds us to stay true to ourselves. For me, these lines sum up so much that my journeying life has been about, and my writing. And it is here that I find the answer to my editing dilemmas:

“Do what thy manhood bids thee do, from none but self expect applause;

He noblest lives and noblest dies who makes and keeps his self-made laws.

All other Life is living Death, a world where none but Phantoms dwell,

A breath, a wind, a sound, a voice, a tinkling of the camel-bell.”

Photos ©Tomoko Goto 2018

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...