Ronald Wright traveled Peru in the 1970’s and 80’s, fresh from university with a degree in archaeology, feeding an obsession with the Inca Empire sparked by a random adventure novel he’d read in his teens.

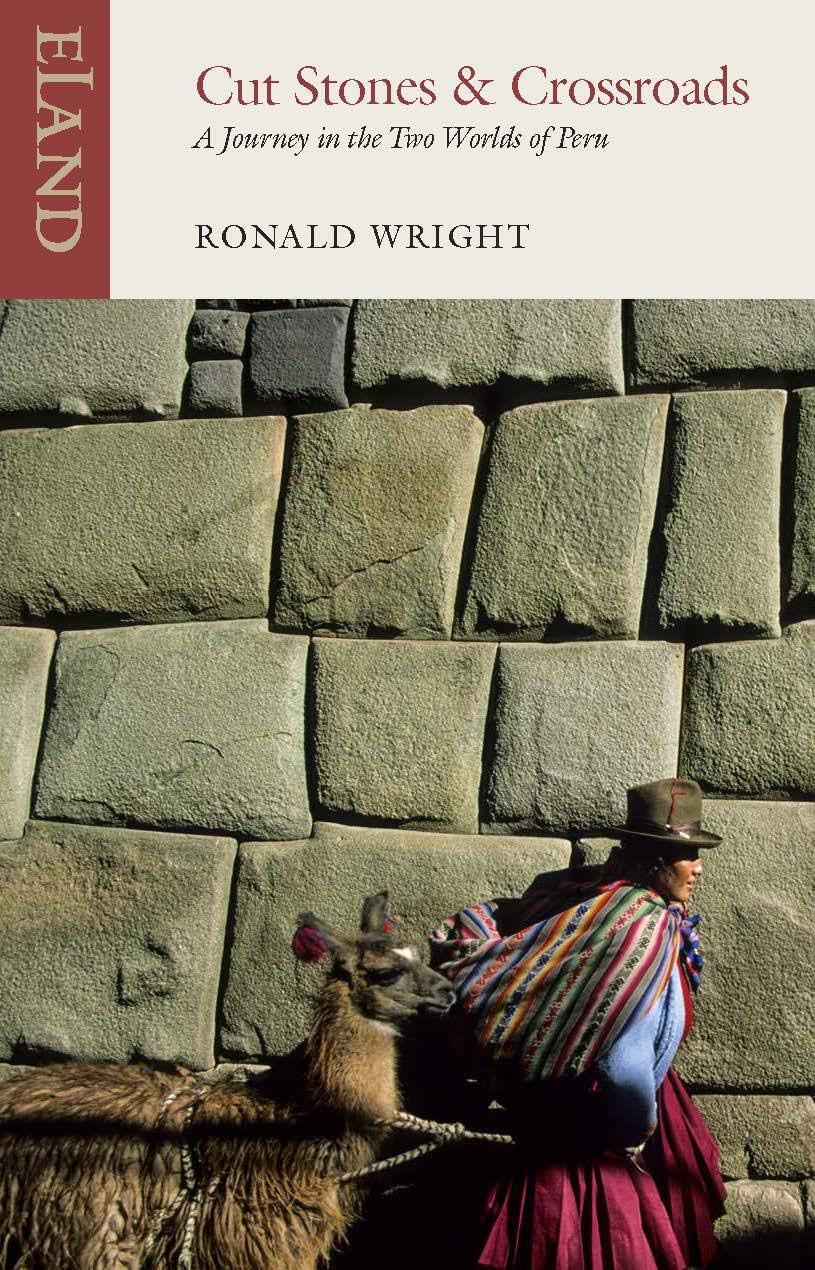

He expected to spend his time wandering ruins, but the ancient world of the Andes was alive all around him in the Quechua still spoken by its people, through the handwoven clothing they continue to wear, and in the traditions and festivals they’ve never stopped practicing.

That world never died; it was just eclipsed.

“I saw that the pre-Columbian civilizations had not disappeared,” he writes. “They have millions of modern descendants still speaking the Inca, Maya, Aztec, and other native languages, still waging a cultural resistance against national elites of mainly European origin. These survivals came to interest me as much as the deep past […]”

Wright captures those “two worlds” of Peru through the slow-motion clash of two incompatible civilizations: the indigenous Inca and their precursors who mainly inhabit the highlands, and the invading Spaniards who morphed over the centuries into the westernized Latin American elites that dominate the Pacific seaboard and the main cities.

His journey traces the story of the Inca in reverse. From Cajamarca, where Atahualpa was captured by Pizarro’s invading conquistadors in 1532, marking the beginning of the end, he travels south, slowly and by way of ruins.

Through stone reminders of the older Chavin civilization and the pre-Inca ruins of Kuelap to Ayacucho, where the blind harpist Antonio Sulca plays him a harawi (melancholy music invoked to lament departures, tragedy and death since Inca times) in a windowless room of his home, with thick adobe walls painted a peeling pastel green.

Details accumulate through a gradual peeling away of layers, material culture and song.

Wright passes through the Inca capital of Cusco, centre of their world, political and religious nexus, stopping to examine minor ruins and quarries along the way.

His encounters prompt quotes from verses and songs; they’re always presented in both Runasimi (or Quechua, the Inca language) and English, because that language preserves the Inca worldview in a living form which compliments their cut stone dwellings and walls.

“Languages describe the world; like art styles, they emphasize some facets of reality, ignore others, and create categories of their own for which there may be no “objective” reason and no parallels in another tongue. Languages shape, and are shaped by, culture as a whole. When people lose their language for another, profound distortions may affect their vision of the world: as if Hieronymus Bosch were suddenly forced to paint in the style of John Constable.”

Throughout his journey, Wright crosses paths with a range of travelers, from a masochistic German who slept under a plastic sheet in a downpour rather than accept space in a tent — “This is all I bring, so this is all I use” — to an elderly American who drove his ancient Dodge van down from Ohio — “…you know the trouble with this country? Latins. They move in: the neighbourhood goes down — we got the same trouble in the States” — and backpackers, hikers, and gringos of every assortment.

He provides a snapshot of these travelers while never losing sight that, though he may have a deeper grasp of the culture, he too is an outsider passing through this ancient land:

“The phenomenon of tourism: the moneyed gringo on a two-week tour who feels as though a National Geographic article has come to life around him; the self-styled adventurer searching for gold and lost cities, but somehow (thank God) his itineraries exist only on napkins scribbled in the Paititi Bar; the hippie mystic on pilgrimage — Cusco, Crete, and Katmandu — seeking the aura of past ages and the local sacrament: cocaine, wine, temple balls; the vagrant scholar (myself?) who turns the pages of this land and thinks perhaps he understands it, but really is looking only at pictures, adding captions gleaned from books. All of us are poaching on a dying civilization to still the hunger of our own.”

The journey ends where the Inca began: on an island in Lake Titicaca, where the sun was said to have appeared on the Rock of the Cat after a period of darkness at the creation of the world.

The Inca appeared here, too — at least in legend — and went on to build one of humanity’s great civilizations.

This deeply empathetic book captures the essence of Inca culture as it clung to mountain peaks and terraced fields for century after century, quietly surviving into the present age.

Cut Stones and Crossroads is now back in print.

Buy a copy today from Eland books ==> Cut Stones and Crossroads by Ronald Wright

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...