I’m moving flats next month and saying goodbye to Tempelhofer Feld, my favourite space in the neighbourhood.

But before I pack up my books and lug them across town, I’d like to tell you a bit about the history of what was once the world’s largest building.

The 1.2 km long complex was built by the Nazis to be the most advanced airport the world had ever seen, but war cut short their plans and they never used it for commercial flights.

When the airport finally closed in 2008, city officials wanted to develop this prime expanse of potential real estate, but Berliners held a referendum and their message was unequivocal: leave Tempelhofer Feld alone.

At a time of housing crisis, when every vacant lot was crammed with cranes and rising blocks of flats, Berliners chose freedom and open space.

On summer days, Tempelhofer Feld — an urban park larger than the principality of Monaco — hosts a lively crowd of barbecuing families, couples walking hand in hand, earnest red-faced joggers pounding out their morning-after repentance, and kite boarders zipping down runways propelled by the wind.

We love to bike over on a sunny Sunday to grab a cold beer and a pretzel at the Luftgarten, not far from the old North runway.

I spend a lot of time at the old airfield, rain or shine. But I only got around to taking a tour of the terminal buildings in the summer of 2018.

As you can see, it took me a little longer to get around to writing it up…

Let’s start with a bit of background on the area.

The vast open expanse that is now Tempelhofer Feld — so called because the land was owned by the Knights Templar in medieval Berlin — was used for maneuvers by the Prussian army as early as 1722.

Given the absence of airplanes in the early 18th century, it would only become a functioning airfield 201 years later.

‘Flughafen Tempelhofer Feld’ began operating in October 1923 with scheduled flights to Munich, and to the East Prussian city of Königsberg (now the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad).

By 1930, its grass airstrips were already handling more passengers than any other airfield in Europe.

A company called Luft Hansa A.G. sprouted its wings here in the 1920’s, growing through a variety of mergers, and serving some 64 routes by 1926, wth destinations as far away as Peking.

But major change was in the air — pardon the terrible pun — including a change in the airline’s logo.

Reichsminister Hermann Göring took over the Germany aviation industry in May 1933, and the airline that would become Lufthansa sported the swastika as part of its livery until that abhorrent political nightmare drove itself into the ground.

When the Nazis took power in 1933 they didn’t just decide the national ideology needed an overhaul. Tempelhof was already over capacity and in need of expansion, too.

In 1935, Architect Ernst Sagebiel was commissioned to design what would become the world’s most advanced airport, a monumental edifice that would be a key structure in Adolf Hitler’s oppressive world capital: Germania.

It was already the first airport in the world to have its own underground railway.

Other airfields at the time weren’t much more than small covered hangars, with shacks on the edge of the runway (Berlin Schönefeld feels a lot like that now).

Tempelhof was built to handle 700,000 to 800,000 passengers, with airport buildings containing some 7,000 rooms.

The greatest innovation were the seven hangars. The curved building at the edge of the apron is 1.2km long, with some 300,000 square metres of space, making it the world’s largest protected building.

I say ‘protected’ not in the sense of some historical designation, but rather ‘protected from the elements’.

The vast column-free cantilevered roof allowed aircraft to ferry passengers right into the building, avoiding Berlin’s often inclement weather and getting them from airplane to terminal door in just 220 metres.

The elegant limestone-clad buildings had separate levels for passengers and luggage, with a U-bahn connection that whisked passengers to the city centre in minutes.

Berlin would eventually spread out to engulf the airport, but that same U6 line is still the one I use today.

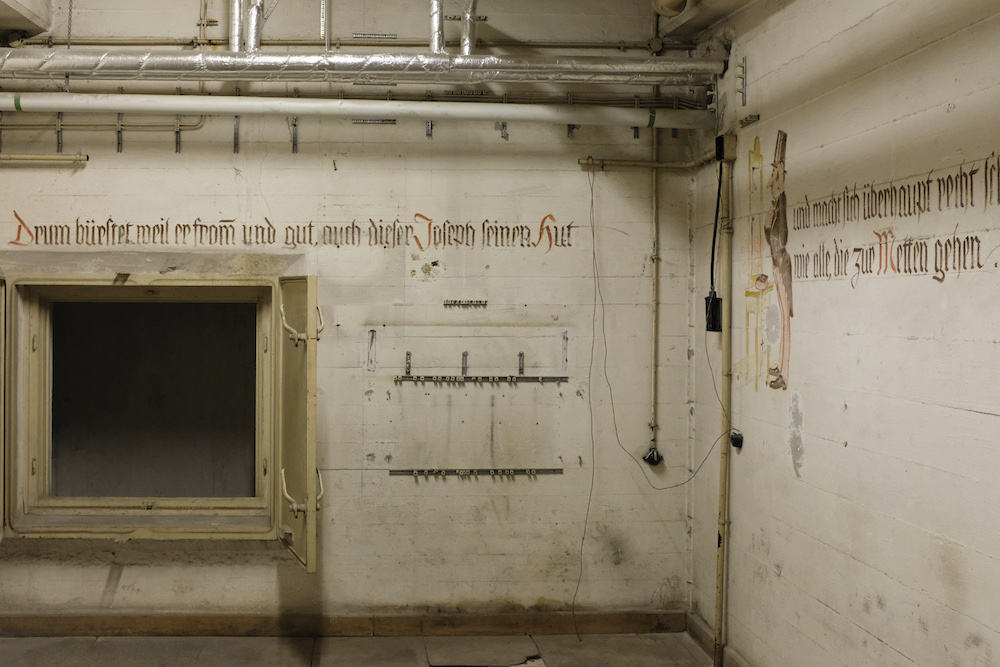

This being a Nazi building, it also came with other less desirable features. Bomb shelters were built throughout the structure, as was true of many public buildings at that time.

And the massive curved roof included reinforced sections designed to hold 100,000 spectators who would watch large scale events in the field below.

Thankfully it would never be used as a stadium for one of the Nazi Party’s horrible rallies. It wasn’t completely finished, either. World War Two broke out before the Nazis could use Tempelhof for civilian aviation.

But what began as the fruits of evil would later be turned to good.

The city was a smoking ruin when Berlin fell to the Allied armies, and Tempelhof ended up in the American sector.

How ironic that one of the world’s largest remaining Nazi buildings would become the centre of the Berlin Airlift during the Cold War, a symbol of freedom in the face of totalitarian aggression.

The massive terminal and airfield built by Hitler was West Berlin’s lifeline when the Soviet Union attempted to drive the Allies away by starving its citizens into surrender with a blockade of all land routes into West Berlin from 1948 to 1949.

The only remaining access points were three 32km wide air corridors that cross the Soviet Zone of Occupation.

The city’s 2.1 million inhabitants needed some 4,500 tons of food, coal and other essentials each day just to survive. And so the nations that worked together to storm the beaches of Normandy and take back Fortress Europe set their might against their former Soviet comrades, too.

The Allies responded by flying 2.3 million tons of freight into the divided city, first at Tempelhof and then also at Gatow in the British sector. Tegel airport would be built by the French in a record 90 days in response to the crisis.

Tempelhof’s grass runways couldn’t handle the demand. The surface was covered with perforated steel matting, but it quickly crumbed beneath the weight of the fully-loaded Douglas C-47 Skymasters, and new concrete runways were installed.

By this time the Berlin Airlift was ticking along like a Swiss watch. If the schedule got gummed up and a pilot couldn’t land, he would simply have to abort and go back to Frankfurt. There was too much incoming traffic to reschedule.

By 6 April 1949, a plane was landing at Tempelhof every 63 seconds, with some 1,398 flights delivering 12,940 tons of cargo.

Tempelhof was also the site of the famous ‘candy bombers’ — so called because the original ‘candy bomber’ Gail Halvorsen started wiggling his wings on approach, before dropping candy to the hungry children watching the landings along the airport’s perimeter fence.

The Candy Bombers provided a badly needed morale boost for the city’s beleaguered residents, dropping some 22 tons of sweets over West Berlin with miniature parachutes.

This unbelievable operation went on every day for just short of a year before the Soviets finally gave up and accepted that West Berlin was there to stay. Their blockade ended at midnight on 11 May 1949.

The U-bahn station and the plaza down the block from my flat is called Platz der Luftbrücke in remembrance of this historic feat.

The US Army would continue to use part of Tempelhof until 1994, when American air and land forces in Berlin were finally deactivated.

The airport was opened to civilian aviation in 1951, providing an important means of exit for East Germans fleeing the Soviet sector — at least until they stopped the exodus of citizens who preferred not to live under communist misery by erecting the Berlin Wall in 1961.

For a while, Tempelhof would be Germany’s busiest airport. But it was finally closed for good on 30 October 2008 — recently enough that my neighbours remember walking down the street to catch a flight.

The former airfield is now a massive public park, as we discussed at the start of this story, and the runways and signs are all still there, faded by the sun and time.

Many of the buildings are still in use, too.

The Polizei rent the largest section, occupying roughly 46,000 square meters (15% of the total space). And the 72 meter radar towed is used by the German army to watch air traffic in and out of Berlin.

Other parts of the hangars and buildings are used to host events, exhibitions, a dance school, and temporary refugee accommodations during the European migrant crisis.

I’ve even heard a group of Canadian expats — including embassy staff — have a ball hockey league in one of the empty hangars.

But my favourite part of Tempelhof is the old airfield.

I love to take a run down the runways, or throw on a backpack filled with road salt for some pre-season training for hiking.

But most of all, we just love hanging out in that vast open space where the skies are wide, and where all sorts of very different people are doing their own thing in a spirt of openness and tolerance.

I’ll really miss this place when we move further west.

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...