We ended our brief Greek travels back where we’d started: in the second-largest city, with one foot in the Byzantine past.

Thessaloniki was founded in 315 BC by King Cassander of Macedonia (one of those who squabbled over Alexander the Great’s empire).

When the Kingdom of Macedon fell in 168 BC, the city was absorbed into the Roman empire. It soon became an important trade hub on the via Egnatia, the road connecting the Adriatic port of Dyrrachium (now Durrës in Albania) with Constantinople.

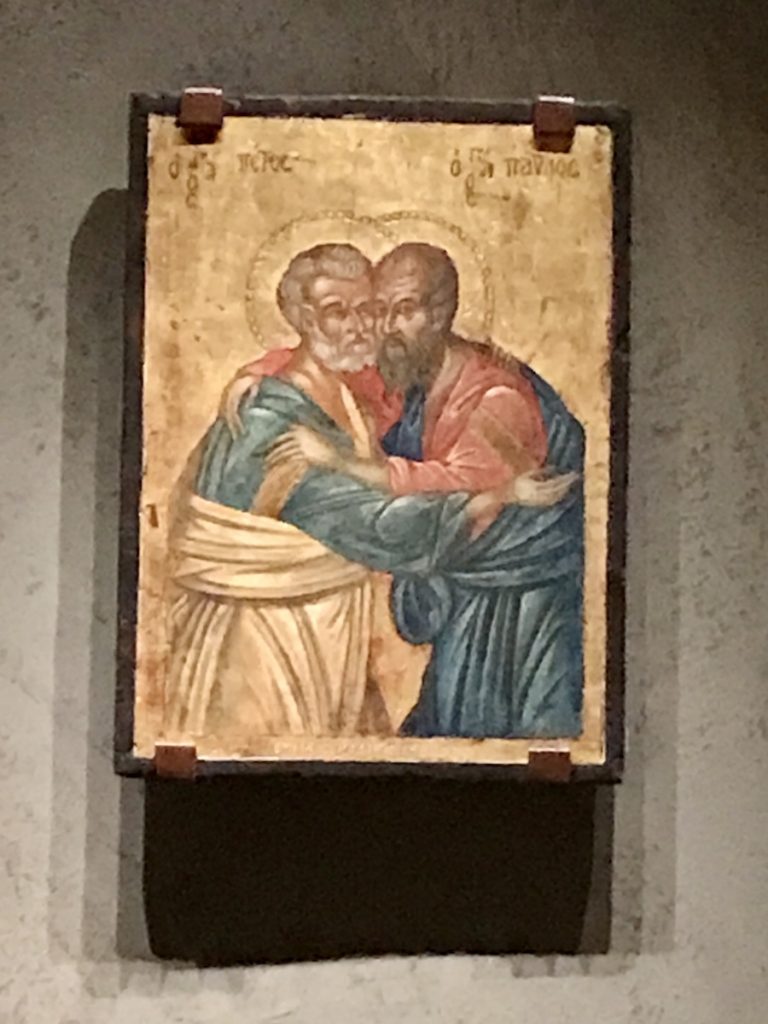

Thessaloniki was also an early centre for the new Christian religion spreading outwards from the Levant. The Apostle Paul preached in the city on his second missionary journey (49 AD), and this laid the foundation for the new cult.

By the Byzantine era, Thessaloniki was second in importance only to Constantinople, and the place was teeming with churches.

You could even say it gave birth to the Cyrillic alphabet. The brothers who invented the Glagolitic script, the oldest known Slavic alphabet, were born there. And when Cyril and Methodius died at the end of the 9th century, their followers created Cyrillic based on their work.

But the glory days under the Byzantines were waning. There was a new empire on the block, and its expansion was relentless. Thessaloniki fell to the Ottomans in 1430, and the Byzantine capital of Constantinople followed in 1453, putting an end to a Roman empire that had lasted for more than 2,000 years.

As in so many other newly conquered territories, the Ottomans transformed churches into mosques. But thanks to unrest in the western Mediterranean, Thessaloniki also saw a new influx that helped transform the city into a multi-ethnic, multi-religious port.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile — the “Catholic monarchs” — ordered all Jews in their territory to convert or be handed over to the Inquisition for barbecuing.

The Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II couldn’t understand why the Spanish monarchs would do this to cultured, highly skilled, hard working people. He responded by inviting Jews fleeing the persecutions to settle in his territory, telling his court, “You venture to call Ferdinand a wise ruler, he who has impoverished his own country and enriched mine.”

For some 200 years, Thessaloniki was the largest Jewish city in the world. The 16th century poet Samuel Usque called it “The Mother of Israel”. But other cultures were present, too, presenting travelers with a vibrant hotchpotch of languages including Turkish, Greek, Bulgarian, Albanian, Arabic, Vlach, French, Italian, Russian, German, and Polish.

The 20th century put an end to this cultural flowering as Europe immolated itself in the Age of Ideology. The city fell to invading Nazi forces on 22 April 1941. By the time their campaign of extermination was over, there were barely a thousand Jews left alive.

As with the far right, so with the far left. The Communists wreaked their own reign of terror when the military branch of the Greek Communist Party fought the government army in a vicious civil war that would last until 1949 and leave the country in a greater state of ruin and economic distress than even the Nazi occupation.

Today, Thessaloniki is Greece’s second-largest city. And it’s as full of life and culture as it was in its historical heyday.

We took an Air BnB flat up the hill, on the edge of the old city, near the street where the wall used to run. It was the most well-outfitted rental I’ve ever stayed in, stocked with snacks, drinks, breakfast goodies, and every toiletry you could think of (and a few you couldn’t).

We arrived rather late in the day, with just enough time to grab a gyro at Psisou, where we were lucky enough to find a table, and a nighttime walk down Nikis Avenue, the city’s busy seaside promenade.

I spent the rest of the weekend plunging into Byzantine history.

Thessaloniki’s churches weren’t as spectacular as what I’d seen in Ravenna, with its vast mosaics of glittering golds, soft grass greens, rich sky blues, the beige and browns of robes, and the odd scarlet of a cloak.

But where Ravenna’s churches were richer in splendour, Thessaloniki’s had wonderful frescoes that leapt to life in the Agios Nikolaos Orphanos church around the corner from our flat.

The church was built early in the 14th century as part of a monastery, and it’s still surrounded by a silent garden that feels like an oasis of calm in the midst of the bustling city. Inside, thick stone walls and graceful vaults were completely covered in frescoes by painters at the height of the Palaeologan Renaissance, that final flowering of Byzantine art that happened during the reign of the empire’s last rulers.

These artists immediately preceded — and did much to influence — the Italian Renaissance, and the works that are still household names today.

Other important frescoes can be seen nearby, just up the hill and a little to the west, in the remains of the Latomos Monastery.

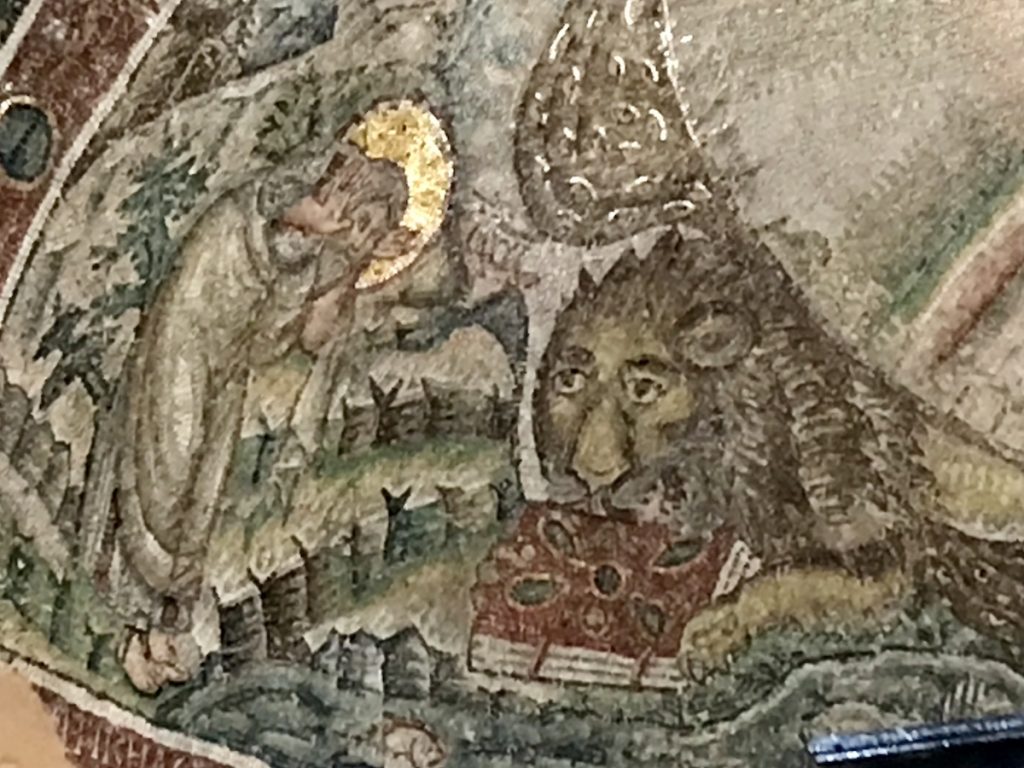

A late 5th-century church is just about all that’s left of the site. But you’ll find remarkable frescoes inside, and a mosaic done in naturalistic style of a theophany — a direct, personal encounter with a deity in physical form. In Greek mythology, seeing a god in its true form would immediately immolate the mortal viewer. But this much gentler apparition depicts JC holding a text, surrounded by symbols of the Evangelists.

The lion with a book in its mouth is clearly meant to represent Mark, but I preferred to see it as a cat who just likes to read. I had a cat like that once. She especially loved to sit on a well-drawn map.

The garden outside the Latomos formed a terrace that jutted out from the hill, with broad views of the city sprawling down the hillside below. I could see how the promenade widened out to the harbour, and the flat sheen of the Aegean where it receded into distant haze.

But I couldn’t sit in the shade for very long. There was more Byzantine history to explore.

We wandered down the hill, popping into more churches from the 5th to 14th centuries. But deeper layers were revealed, too. The Roman forum and Bey Hamani Ottoman bath sat at opposite ends of the same block, two eras and two faiths coexisting in sun bleached stones.

The vast sunlit expanse of Aristotelous Square was the perfect place to stop for a frappé, that hallmark of Greek coffee culture invented in Thessaloniki by a Nescafe rep called Dimitris Vakondios in 1957.

I spent the rest of the day at the city’s excellent Museum of Byzantine Culture, where artifacts put a human face on an era I’d first read about in John Julius Norwich’s highly readable three volume history.

And then the long trudge up the hill through intense heat — with a stop to cool off inside the six metre thick walls of the Rotonda, built in 306 AD by the Roman tetrarch Galerius for his grave, repurposed as a temple, converted to an Orthodox church, and then a mosque, and back to church again.

And finally, a chilled carafe of retsina high on the city’s old Byzantine walls as the sun sank and lit the Aegean with an orange the shade of butternut squash.