Christmas passed largely unnoticed while I was in Istanbul. Traditional holidays don’t have the same glow when living far from friends and family. Instead, they’re a reminder of what we give up to live a life abroad.

I tend to spend December 25th walking. I don’t plan to; it just works out that way.

On my last Christmas in Malta, we walked across lonely garrigue searching for the ruins of a Roman farmhouse. In other years we went walking in the Moroccan High Atlas, or clambering through Agamemnon’s old stomping grounds in the Peloponnese.

This past Christmas we hopped the T1 tram to Eminönü in search of a ferry up the Golden Horn.

The boat we wanted no longer stopped at that pier, but a man sipping tea outside a kiosk directed me to a smaller boat that would take us across to Kasımpaşa, where Ottoman dockyards once built ships to rule the Mediterranean waves.

The Golden Horn ferry picked us up 20 minutes later for a zig zag ride up the inlet to Ayvansaray, the meeting point of the old Byzantine land walls with the water.

I never made it here on my first visit to Istanbul — I don’t think I even knew about its significance back then — but on this trip it was at the top of my list.

I wanted to walk a long stretch of the Theodosian Walls, and to look up at them from the outside and imagine what the barbarians must have thought when they came up against them.

Built by the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II in 413, they ran for 6.5km, from the Golden Horn in the north to the Sea of Marmara in the south, closing off Constantinople’s entire landward side.

The other sides of this peninsular city were defended by water, by stout sea walls, and by an enormous chain that could be stretched across the mouth of the Golden Horn to close the inlet and its harbours to intruders.

An earlier wall had been built by Constanine I around 324, and it defended the city from the Goths in 378, but the population of Constaninople was growing beyond the boundaries he’d imposed and new defences were needed.

That job would be done by Theodosius II, as I mentioned above. Alarmed at the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410, he ordered the construction of a massive triple-fortified barrier that would ensure the Eastern Roman capitol would never suffer the same fate.

These new walls were set further back on the peninsula, expanding Constantinople’s enclosed area by 5 square kilometres.

Damaged by earthquakes but quickly repaired, the Theodosian Walls were the medieval world’s largest and strongest fortifications.

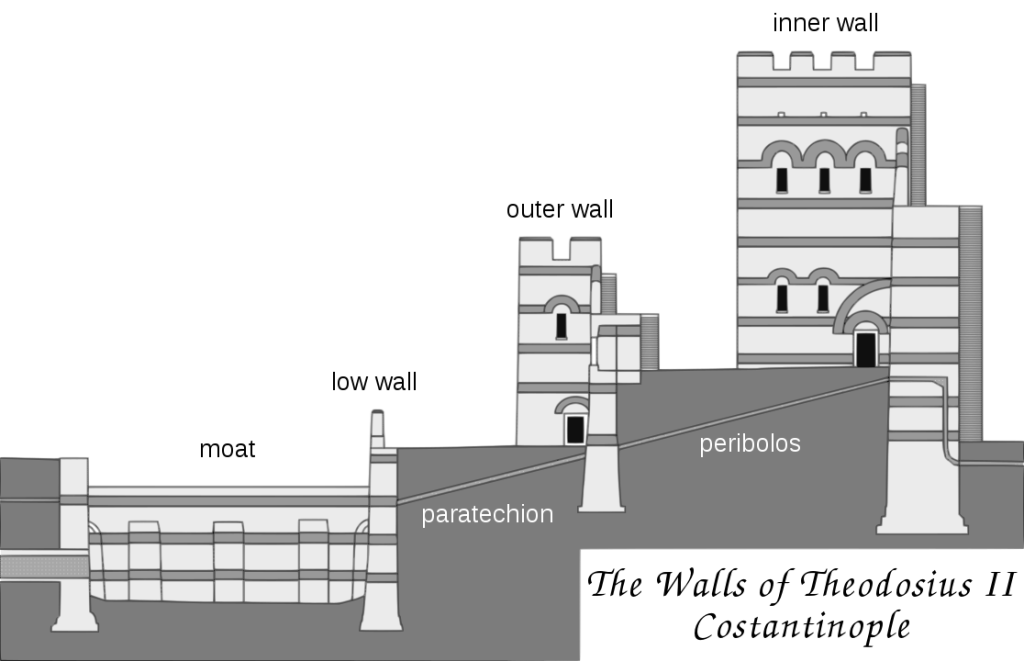

An attacker approaching the city from the landward side would first have to cross a moat, 20 metres wide and 10 metres deep, backed by a 1.5m crenellated wall. That wall was topped by a terrace which could be occupied by soldiers via postern gates.

Should our attacker manage to cross both moat and terrace while under fire, he would come up against the 9 metre tall outer wall with its regularly-spaced 14 metre tall towers.

You’d think successfully scaling this wall would swell any attacker with feelings of euphoria, but it would be quickly replaced by dread.

Our attacker is now standing on an inner terrace called the peribolos, trapped between the outer wall and the even larger inner wall, 12 metres tall and defended by 96 regularly-spaced towers that were 20 metres tall and armed with catapults and ballistae.

This would be the last thing our attacker saw as he fell beneath a hail of arrows, or was consumed by excruciating tongues of ‘Greek fire’.

The walls had been constructed such that the towers of the lower outer wall alternated with the massive towers of the inner wall, giving both clear fields of fire downwards at besieging attackers, and out over the plains beyond.

Each tower was topped by a battlemented terrace. The interior was typically divided into two chambers. The lower opened onto the city and was used for storage. The upper could be entered from a walkway high on the city side, where windows provided both a view and an opening for firing projectiles.

So many assailants spilled their blood against those walls. The Avars and Persians besieged them in 626. The Arabs failed in 674 and again in 717-718, and the Bulgars tried their luck in 813. Even the mighty Mongols took one look at them and turned away in search of easier targets.

They were followed by Goths, Slavs, Rus, and others, but the walls of Theodosius held strong through some 24 sieges.

(I don’t include the siege, sacking and occupation of the city by Christian Crusaders in 1203 and 1204. Their campaign was largely fought in the Golden Horn against the city walls.)

The Theodosian Walls stood impregnable for nearly 1,000 years, until the advent of a new age of warfare brought gunpowder and powerful siege cannons to crack the impossible obstacle of an earlier era.

Determined to take Constantinople once and for all, the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II assembled a massive army in 1453, and commissioned the largest cannon ever made to pummel the weakest point on the walls.

The city fell on May 29, 1453 after a 53 day siege, bringing the glorious Byzantine Empire to an end and ushering the Ottoman Empire onto the world stage.

The Theodosian Walls are crumbling in many places, but they’re still standing 568 years after the Ottoman conquest.

There isn’t anything left of the old Byzantine palace of Blachernae, where the walls meet the Golden Horn at the start of our walk. It was swallowed by Istanbul long ago. Today the crumbling inner wall is backed by a cluster of poor working-class houses where radios echo inside tidy homes and cats sprawl on sun-warmed stones.

Further up, at the crown of the hill, portions of The Palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Tekfur Sarayı in Turkish) have been restored, giving a sense of what this corner of the Blachernae palace complex may have looked like in its prime. This was probably the last Byzantine imperial residence built in Constantinople, sometime during the 13th or 14th century.

There isn’t much to see inside, just empty rooms and a few displays of tile, but the view from the roof provides a vast panorama of modern Istanbul’s growing sprawl, with sun glinting off the Golden Horn and the Galata Tower in the distance.

The Theodosian Walls stretch into the distance, too.

The English Romantic poet Lord Byron said of them, “I have seen the ruins of Athens, of Ephesus and Delphi: I have traversed the great part of Turkey and many other parts of Europe, and some of Asia; but I never beheld a work of nature or art which yielded an impression like the prospect on each side from the Seven Towers to the end of the Golden Horn.”

We continued to walk the walls, stepping outside at each opening to ponder the attacker’s view, still intimidating after all these centuries.

I wanted to visit the Kariye Cami — home to what must be the world’s finest Byzantine frescoes — but the former church is now a mosque, and was closed for restoration.

We walked as far as the Topkapı gate, where Mehmed II punched a hole in the walls and took Constantinople on the morning of May 29, 1453, a Tuesday under the old Julian calendar.

A small plaque marks the spot that put an end to one of history’s truly great empires. And that plaque marked the end of our walk, too.

After a stomach-warming cup of tea, we hopped a tram back through the centre of the old town to the busy piers of Eminönü for a fish sandwich and a cup of fermented turnip juice next to the Galata Bridge.

And then we caught another ferry to Asia and the busy district of Kadıköy, where the British Turkophile writer Jeremy Seal had recommended Çiya Sofrası — specializing in traditional Anatolian dishes — as the perfect place for our evening meal.

I was halfway through a plate of köfte before I realized it was Christmas dinner.

Merci for make us Traveling with your eyes! Additional knowledge and perception that you bring with your pen is a must.

Glad you enjoyed this one, Harry. It’s an incredible feat of human ingenuity.

I was just in Istanbul and could find no information as to the exact location where the Ottomans punched through the walls and entered the city. This is a fantastic explanation of not only the walls but where history occurred, and I regret not finding your website when I was there.

Most guides I found started at the Chora Church (now a Mosque and still closed for renovation as of July 2022). These guides then lead one to the right along the walls (with the old city at your back) toward the Golden Horn. In general, I was disappointed with what I saw. Ryan’s website has one walking to the left (again, with the old city at your back) through the various gates, including the historic area where the Ottoman’s stormed the city. It looked far more interesting and I suggest anyone who is interested in the history of the walls to follow his directions.

Well done! An excellent, well written and informative website.

I’m glad it was helpful, Dan. Sorry you didn’t find it before your walk.

Great article Ryan. I plan to walk this wall in September. Besides the main gates and touristy chunks, did you find any off=the=beaten=path curiosities along the wall.. or any unique shops, stalls, or restaurants?

I remember that neighbourhood along the wall being very interesting. And I especially liked seeing the gate where the Turks first breached the walls.