We would visit many other casbahs during our stay in the oasis, but none held the peace of our rooms at Ben Moro. I finally bumped into the owner of our casbah, and asked him how a Spaniard had ended up in such a remote desert place.

“I found it twenty years ago,” he said. “I wanted to restore an old casbah. I’m sure you’ve noticed this valley is full of them. So I just asked around until I found a family who wanted to make some business, and we worked on it together.”

It wasn’t his first such venture in Morocco. That had been a small house in a remote mountain village he’d stumbled on two decades earlier while exploring the region by Land Rover.

“That village made a good base for hiking. I kept going back, year after year, and I got to know a local man who acted as a guide. When his family ran into trouble, I bought their home, and we turned it into a guesthouse. It’s where I really fell in love with Morocco. I think you must go there if you have time.”

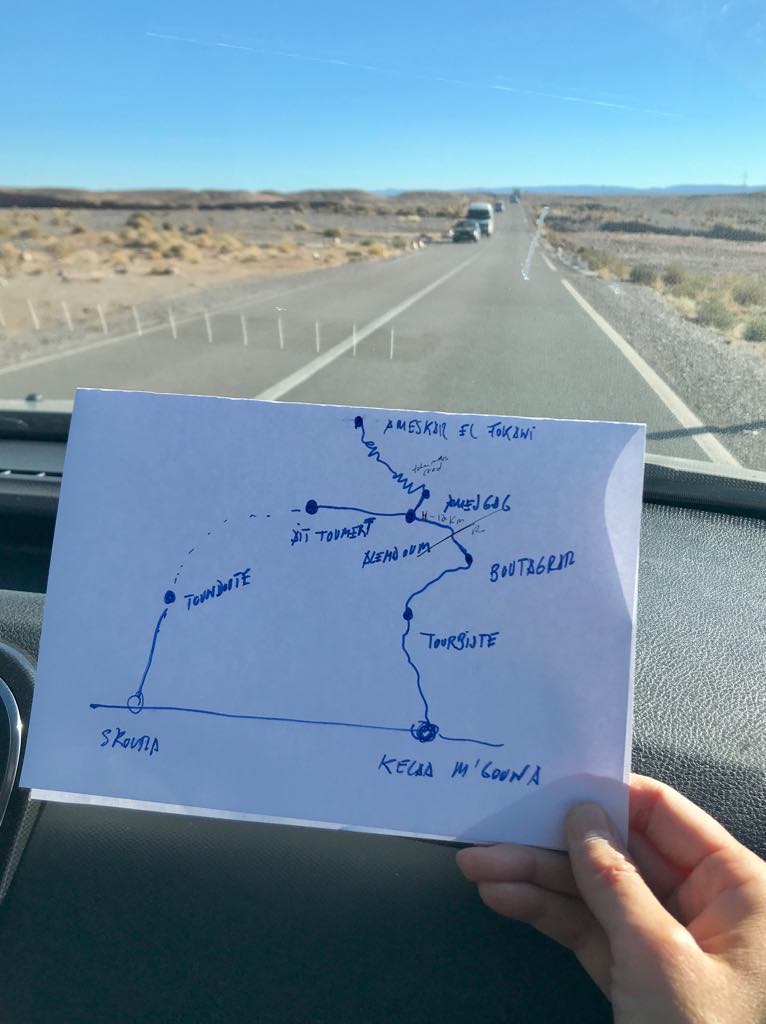

True to his word, he presented us with a hand-drawn map the next morning, and we set off to locate his lost Shangri-La.

Our route took us northeast on the main desert highway to the busy town of Kalaat M’Gouna. “Turn at the roundabout with the enormous rose monument,” he’d said, “and follow that road to the end.”

This was the Valley of Roses, a Berber region where flowers scent the air each April and May, and villagers fill their waking hours meeting the demand of the world’s rose water trade. By some strange coincidence, the world’s other major producer of rose water is Bulgaria, a country we’d passed through on our previous journey.

The road led us up a steep-sided valley of red rock streaked with grey. A river trickled through the bottom, and cultivated land filled the flood plain, punctuated by the occasional gnarl of mature trees.

The valley was scattered with ruined casbahs placed atop commanding rocks. Small villages clung to their walls, and clustered at the points where tributary streams slipped in.

We paused for a break in the village of Hdida, where I’d spotted an inviting terrace overlooking the broad valley floor. The proprietor plucked rosemary into the pot rather than the ubiquitous mint. He said this was common in mountain regions, but his kind smile turned to disdain when he saw my embarrassing failure as a tea pourer.

I was told to dump it back into the pot, and to pour it again from a much greater height. The tea frothed into the tiny glass, forming bubbles that seemed to please the man, but filling a glass the size of a thimble at arm’s length required the accuracy of a bombardier.

The sickly-sweet tea restored my flagging energy, and we pushed onwards and upwards. The desert valley continued to climb.

The red of the rock and the barren brown ground contrasted with the deep blue of the sky, and the green of the trees that lined the valley floor. This was a peaceful land of primary colours, and of primary needs.

At a crossroads town beyond a bridge, we followed the jagged line of our hand-drawn map through a river-valley piste that would have horrified the rental car company had they been there to see it.

Thankfully it linked to a good gravel track that wound up and over a mountain, with views of the entire Valley of Roses with its casbahs below us.

Our destination was Ameskour El Tokawi, a tiny village nestled in a cleft of the mountains. When I asked an old man if he knew the proprietor of the house we were looking for, he slapped the hood of my car and walked ahead.

I followed in first gear, down a narrow mud track between buildings to the gate of the thatched-roof family home that Juan the casbah owner had turned into a base for hiking.

We shared tea with the family who owned the house, and a massive Berber omelette of eggs poached in a smokey paprika and tomato sauce, dusted with saffron and served in a massive tajine.

The crusty bread we used to dip up the sauce had come freshly baked from the family’s own oven, and it was still hot to the touch.

I would have loved to stay there for weeks, to hike the surrounding peaks by day and steam myself in the little hammam off the courtyard each evening. But we had a very long drive back to the oasis, and it was already growing dark.

Safely back in our casbah after a disorienting four hour journey down nighttime roads — and a heaping plate of couscous in a bustling bus stop town — I sprawled on the sofa by the fire with a glass of blood red Moroccan wine.

My reading brought on troubled dreams as the paranoid world of displaced people conjured by Bowles became a James Bond story in my mind. Daniel Craig was Bond, but I was pursued, seeing the scene through my eyes and his.

The situation was about to resolve itself in some sort of gunfire when the donkey in the pen below our window woke me with his cheerful morning cry as he greeted the old man who brought his sunrise meal.

Photos ©Tomoko Goto, 2019