Life has settled in to that early January feeling of listlessness when the holidays are over, New Year motivation has fizzled out, and fresh projects are sitting on the desk but the means of starting them hasn’t yet been revealed.

I guess part of me is still back in Ireland, where I’m wandering through an earlier age moistened by mists of rain.

Unable to bear the thought of spending Christmas week enduring the out-of-control toddler whose shut-in family occupies the flat above, we flew to Dublin on the 24th and drove across Ireland to Co. Kerry, stopping for groceries along the way. Everything would be closed over Christmas and we would have to fend for ourselves.

A peat fire was already blazing when we arrived at the perfect Air BnB flat just outside the village of Killorglin, midway between the Dingle Peninsula and the Ring of Kerry.

The latter was our Christmas Day destination. It’s incredible how quiet a place normally jammed with tour buses and rental cars can be on December 25th.

Fortified by a good Irish breakfast of eggs, black pudding and pork sausages, we set out on Christmas morning along the N71 through Killarney, over Moll’s Gap and along Kenmare Bay.

Not far from where the river opens its mouth to the Atlantic, we turned off the main road behind Castlecove and wound up single-track country lanes, past meadows and sheep farms, to an Iron Age structure nestled at the head of a valley next to a stream.

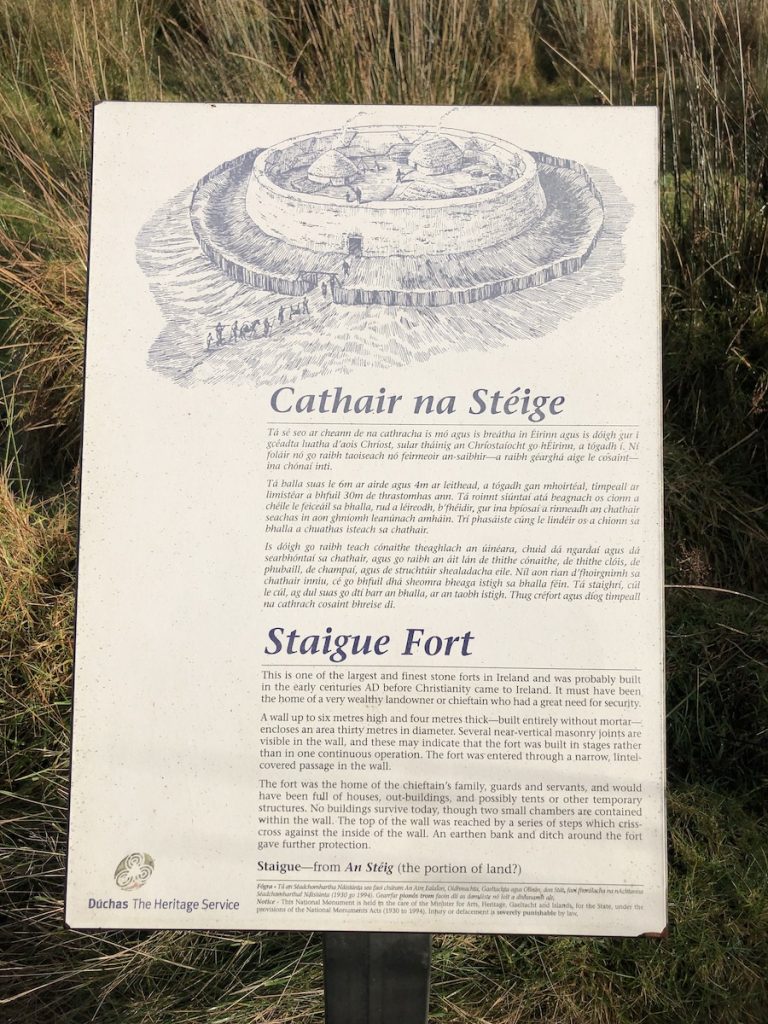

Staigue is one of Ireland’s largest ring forts (an Stéig or Caiseal Stéig in Irish). Around 45,000 structures of this type are scattered across the Irish countryside, some made of earth and others of stone.

The term ‘fort’ is a bit of a misnomer. These structures were more likely used as enclosed farms, with space for sheltering animals as well as round domestic dwellings built of timber, with walls of wattle and daub.

Other structures may have been present within the enclosure, too: kilns for drying grain, workshops and other sheds.

Staigue didn’t look terribly imposing from the road below. Situated on a mound and encircled by a still-discernible earthen rampart and bank, its dry stone walls rose to some 18 feet (5.5m), enclosing an area 90 feet (27.4m) in diameter.

It was only after we passed through a low entrance roofed with double lintels that I could see the walls were 13 feet (4m) thick, built entirely without mortar, using undressed stones.

Its other unique feature is a pattern of drystone steps built into the surrounding wall: ten flights made in an X-shape that give access to the rampart.

It was easier to gain a sense of the size of the enclosure from above, situated as it is with brooding hills in the background, and a shifting sky that brought deep greys, a glimpse of blue and rainbows in the span of five minutes.

Looking back the way we’d come revealed commanding views of Kenmare Bay, with the rocky hills of the Beara Peninsula whispering a call to adventure just beyond.

Inside, at the base of the walls, two openings led to corbel vaulted chambers — souterrains — that may have been used as places of refuge or for the storage of food.

This fort was likely built in the late Iron Age, somewhere between 300 and 400 AD, and — given its size and solidity — may have housed a local chieftain or king, with those of lower rank spreading their dwellings below the surrounding earthen rampart. But these people are lost in antiquity and we can only imagine their lives.

There wasn’t a soul to disturb the peace as I stood on the ramparts and looked out to sea, wishing I had more time and a map to wander the hills in search of standing stones. But daylight doesn’t last long in December this far north.

And so we climbed down from the walls and walked back to the car, where we ate roast beef sandwiches and an apple in silence before threading our way down country lanes to the main road, and onwards to the town of Ballinskelligs to look at the remains of McCarthy’s Castle and a ruined Abbey.

Christmas dinner would be a pint of Murphy’s stout from a can and servings of steak and kidney pie from the grocery store, followed by more map reading to plot the next morning’s course.

I can’t think of a better way to spend a quiet holiday far from home.

Photos ©Tomoko Goto 2022