Eric Newby wrote that the “Dingle Peninsula contains within it one of the greatest concentrations of ancient remains in Ireland.”

Much of this is located at its far end, where religious ascetics shivered their way to salvation in damp stone huts whose sparseness must have accelerated their journey to the afterlife.

That’s where we headed on Boxing Day — Dingle, not the afterlife, though the full Irish breakfasts I was consuming likely weren’t doing my sedentary writer’s arteries any favours.

December 26th was relatively sunny with only a few lashings of rain. Our first stop was a collection of beehive huts — clochán in Irish — built on a sloping hillside with views of jagged Skellig Michael vanishing in and out of rain squalls that made their first Atlantic landfall on these rocky shores.

When I pulled the car to the side of the road, the farmer whose land includes these huts shuffled out his front door to a little kiosk he’d built beside a sheep gate. I handed him a couple euros each for the site’s preservation. He mumbled something about the weather in a thick accent tinged with Irish, and handed me a single page information sheet in return.

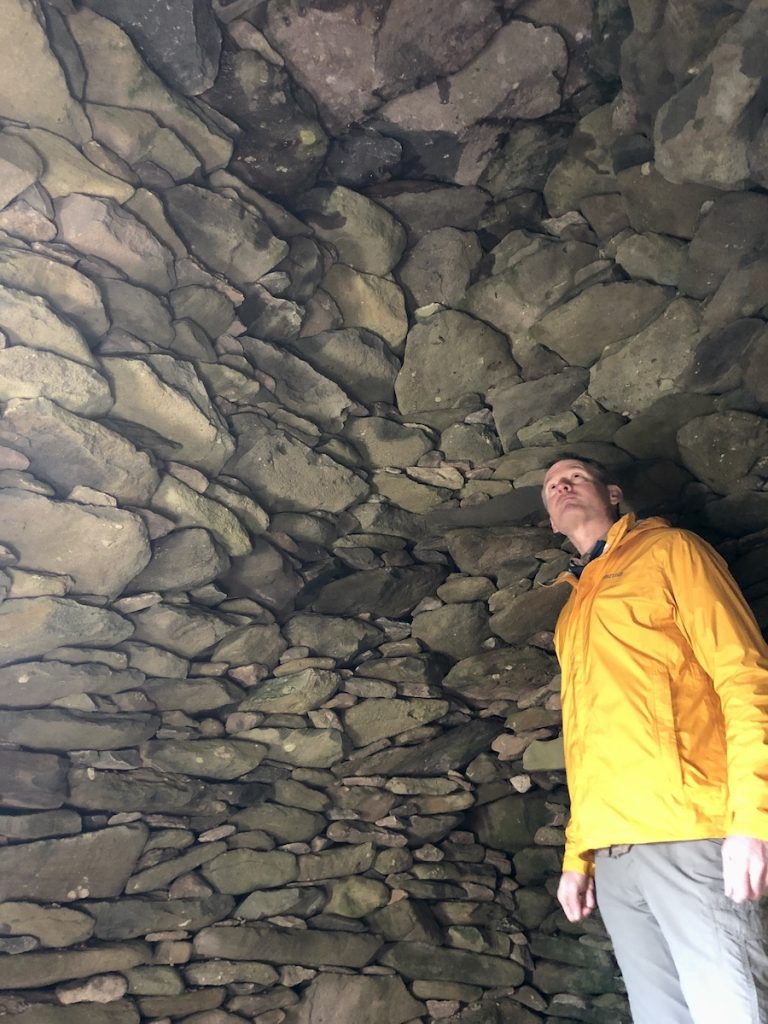

Like the Iron Age ring fort we’d explored on Christmas Day, these huts were constructed entirely without mortar, built layer by layer with carefully stacked rings of stone, each of which was positioned a little more inward until they met in a domed roof.

It isn’t easy to date such structures because corbelling was used for thousands of years in Ireland, and it wasn’t just confined to religious devotees with a fetish for severe self-denial.

The beehive huts we were huddling in were probably occupied by hermit monks from the 8th to 12th centuries AD (and for an undisclosed time by a sulking Luke Skywalker in the worst Star Wars film).

There are hundreds of them in various states of ruin scattered across the Dingle Peninsula. A few can even be found inside the thick surrounding walls of a ring fort.

Cashel Murphy, just down the road, is one of them. Another sheep gate led to a hillside enclosure with a locked metal box and a sign requesting a small donation for entry, something I’m happy to support if it goes to preserving these precious relics of our collective past.

The thick stone wall enclosing a collection of five connected clocháns on the slopes of Mount Eagle is believed to date to 3200 BC, and was likely occupied from the early medieval period to the 13th century AD. Five extended families would have lived in these huts, surrounded by their livestock, which could be brought into the enclosure at night.

Like many other ring forts from the period, this one had a souterrain — a narrow subterranean passage believed to be used for hiding from enemies or the storage of food.

I spotted it immediately as I surveyed every corner of the ruin. My wife was busy taking photos but she spotted me just as I was hitching up my pants and preparing to investigate. The opening was a bit of a squeeze, with a shallow entry depression that stepped downwards and inwards and downward again.

Thankfully there wasn’t a soul around to hear the shouting that accompanied my rather deft feat of contortionism, not from me but from my distressed wife, whose Japanese standards of spotlessness were in danger of being severely muddied by my subterranean slithering.

Once through the entrance, the passage was slightly roomier, with just enough space to squat and peer into the gloom. The walls were built of corbelled stone, like the huts above, and it trended downwards, but the darkness was too thick to penetrate with only the light of a phone.

I crept forward a little, attracted by the description I’d read of a chamber deep beneath the walls, where the sun angled in to light a carved stone at the end of the tunnel twice each year. But it was too dark to see if I might find myself wedged, unable to turn around.

I hauled myself out with great reluctance and some difficulty, my feet slipping on wet stone and my back scraping the exit, bitterly lamenting the lack of a proper head torch, an item I resolved to never again travel without no matter how civilized my destination.

A squall passed over from the sea, bringing wind and lashing rain, and so we trudged down to the car, where my wife stood outside carefully scrutinizing the soles of her shoes for sheep shit while getting slightly soaked.

The road continued around the edge of the slope to Slea Head, with views of the now abandoned Blasket Islands and the rock-strewn seas where two marauding ships of the Spanish Armada — the San Juan and the Santa Maria de la Rosa — struck stone and sunk in 1588.

The Blaskets were once home to some 175 Irish speakers, but the population had declined to 22 by 1953, and residents were moved to the mainland the following year by a government that could no longer deliver basic emergency services to this beautiful westernmost settlement in Ireland.

Unlike the islanders, the Spanish Armada hadn’t arrived on these shores voluntarily. The 130 ship had fleet set sail to invade England along with an army from Flanders, but a skirmish in the English Channel scattered the aggressors and drove them into the North Sea. Many ships were damaged, and error brought them too close to the dangerous Atlantic coasts of Ireland and Scotland.

Of the vessels that sheltered behind the Blasket Islands, two sunk in the reef-strewn waters, but the commander’s galleon and a few others were able to get back to Spain when the winds changed a few days later. Those unlucky survivors who were captured ashore were put to death in Dingle. In all, some 33 ships were sunk off the Irish coast, and thousands of Spanish sailors drowned or were executed by the Crown.

It’s an odd bit of naval history, but it was soon swept from my mind when we reached the cliffs of Dunmore Head and paused to stretch our legs on Coumeenole Strand. The tide was out, and a father and son were kicking a football on the flat stretch of sand. Beyond them, a woman in a short wetsuit was braving the waves for a Boxing Day dip.

We sought elevation by climbing the nearby headland for a glimpse of the film location from the horrible Last Jedi instalment of my childhood-shaping space saga. It was here that Luke Skywalker had sunk his X-Wing fighter beneath the waves of what — in film land — was a cove of his island exile. It was all CGI, of course, and there was no star fighter to salvage.

Robbed of the opportunity to explore distant desert planets, we plunged back into the past instead.

Gallarus Oratory is one of the peninsula’s most remarkable structures. The boat-shaped pilgrim’s hut or early Christian chapel is thought to have been built between the 6th and 9th centuries, and its incredibly precise corbel stone work is still watertight. Unlike the beehive huts I poked my head into earlier, the oratory’s outer sides are completely smooth, and the stones are set on a slight angle, allowing water to run out of the interior.

Ireland is threaded with pilgrimage routes, and an 18km path called Cosán na Naomh (The Saints’ Path) passes by this stone reminder of a distant and more pious time.

A little further along its way, made much shorter by car, we found the roofless remains of Kilmalkedar (Cill Maoilchéadair), a mid 12th century church associated with Saint Brendan the Navigator.

After examining the stone work of the church walls, I wandered the graveyard, where I found an Ogham stone from the 5th or 6th century, carved with early Irish inscriptions, and a tall stone sundial with rectangular shaft and semi-circular head.

The rod was missing, and so I wasn’t able to tell the hour, but it served as a reminder that the day was growing late. It was time to drive back to Dingle town for a pint of stout and a bite to eat.

Little did we know that December 26th is more than just Boxing Day, or St. Stephen’s Day, in Dingle.

It’s also the date of a strange festival with origins lost in the mists of Celtic mythology. I’ll tell you about what we walked into — and stumbled out of — in the next blog.

Photos ©Tomoko Goto 2022