We left Killorglin early the next morning for the long drive across Co. Limerick to Tipperary, with stops for strong lashings of Bewley’s tea to inject alertness into a blustery grey day.

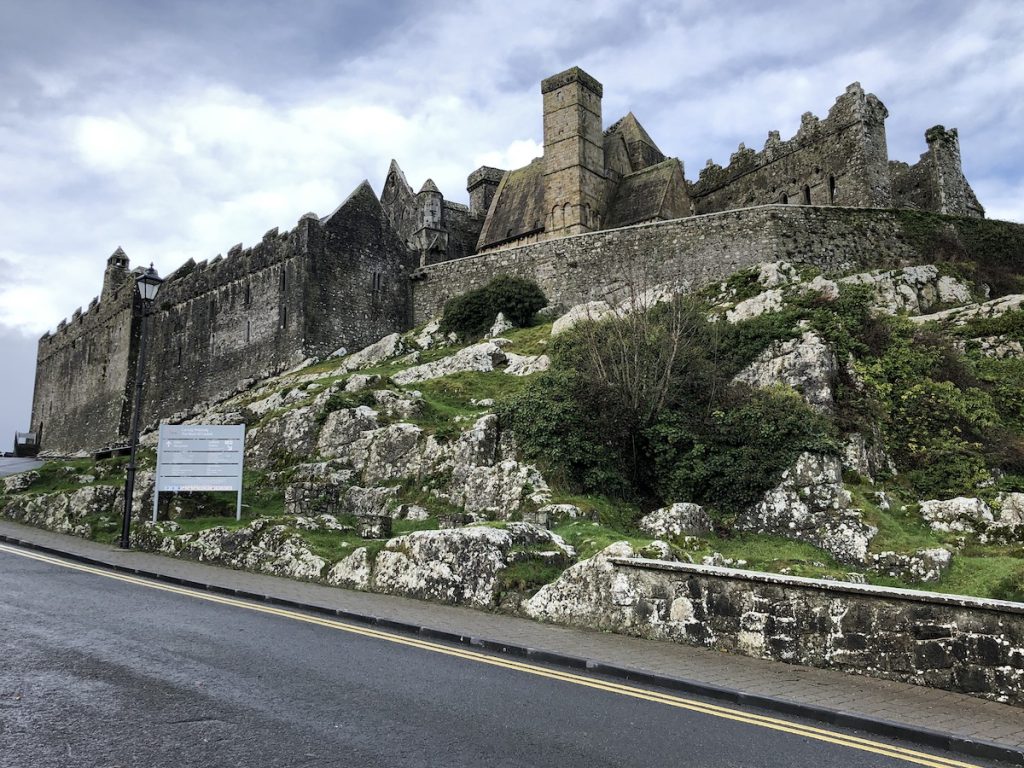

Our destination was the Rock of Cashel, a remarkable cluster of medieval buildings erected on a 60m (200 foot) limestone outcrop with commanding views of the Tipperary plain.

Long before Christian pilgrims graced these emerald shores, this imposing hill would have been a centre of Druidic worship, and like so many other places in Ireland, it held the whispers of faiths that had passed through before.

Cashel’s role as a ceremonial centre for the Kings of Munster began in the 4th century AD. According to legend, St. Patrick himself came here to convert King Aenghus to Christianity.

The great Brian Boru was made High King of all Ireland there in 978, putting an end to the domination of the O’Neill’s (my mother’s ancestors) and quite possibly to the Viking invasions.

His grandson gave the Rock to the church in 1101, not out of piety but to prevent his rivals — the up-and-coming McCarthy’s — from seizing this strategic and symbolic place. If it belonged to the church instead, then McCarthy’s power base would be preserved and he would gain serious local esteem for Christian virtue.

The Rock of Cashel quickly rose to prominence as one of Ireland’s most significant centres of ecclesiastical power.

The 12th century round tower is the oldest building on the hill, a 27.9 metre high structure of coursed sandstone and limestone, with a door set 3.28 metres above the ground. These uniquely Irish edifices probably began as bell towers, but they would have been used by monks to shelter themselves and their precious manuscripts during the Viking raids.

The Rock’s largest building, the 13th century Gothic cathedral, is a cruciform church without aisles — and now also without a roof. At its back, a stout square tower house was added in the 15th century as the archbishop of Cashel’s residence. The choir also lived on the Rock, in a smaller detached building called the Hall of the Vicars.

A cold and surprisingly bitter wind swept the hill on the afternoon of our visit, dropping the temperature by several degrees from that of the car park below. It was the sort of wind that cuts through all but the thickest wool sweaters, bringing gentle dustings of rain.

The ticket machine was broken that day, and so we were given free admission. As luck would have it, one of the site’s resident historians was about to begin a guided walk.

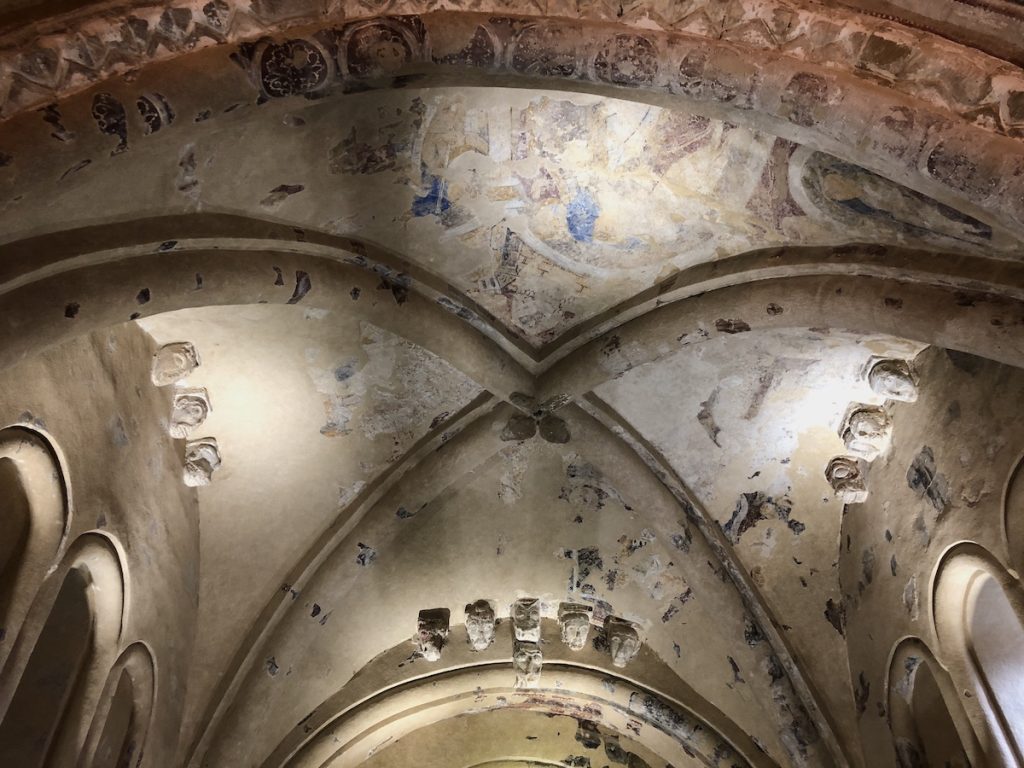

Because we were such a small group, three days after Christmas, and because a few of us were so deeply interested, we had the good fortune to be taken inside Cormac’s Chapel to view Ireland’s only surviving Romanesque frescoes.

The little church that abuts the massive Gothic cathedral was begun in 1127 and consecrated in 1134 as the chapel of King Cormac MacCarthy. The building itself is a unique blend of native Irish and contemporary European architecture, with a barrel vaulted ceiling, a carved tympanum over both doorways, and Germanic twin towers on either side of the junction where nave and chancel meet.

No one in medieval Ireland would have had the skills to build this church, infused as it was with Continental influences. The Irish Abbot of Regensburg, Germany had sent two of his carpenters to help with the work.

Unfortunately, the chapel’s sandstone structure didn’t suit the island’s damp climate. The frescoes have been badly damaged and are now enclosed in a rain-proof carapace, with interior dehumidifiers to dry out the stone. The building is kept locked, and entry is strictly limited because even the humidity of our breath could speed its decline if enough people trooped through.

We emerged blinking into sunshine and bitter wind, and wandered through Ireland’s most magnificent cluster of medieval buildings until a fresh squall pestered us to the car.

But that was not the end of our ecclesiastical adventures. The plains around the Rock are littered with half-forgotten abbeys, most of them abandoned around the same time as Cashel, when the invading English forces of Oliver Cromwell attacked the town in 1647 and massacred the 1,000 residents who sought shelter in its Gothic Cathedral.

My Ordnance Survey map of the South marked the site of several ruined Abbeys. I wanted to find one in particular, which seemed to be a short drive outside of town.

I’ll tell you about it in the next blog.

Photos ©Tomoko Goto 2022