Europe wasn’t always the centre of world culture.

In the Early Middle Ages, after the fall of the Roman Empire, most of the continent was a pestilential backwater of ignorance, declining trade, squabbling princes and corrupt priests.

If high culture and learning was what you wanted, you would have been wise to hitch your ox cart for Central Asia — the centre of the commercial world.

Transoxiana and Khorasan, in the territory that is now Uzbekistan, reached its intellectual peak in the 9th and 10th centuries under the Samanid dynasty.

There are some 51 monuments and 250 assorted buildings inside Khiva’s old city walls, but it’s difficult to get a sense of what they looked like in their heyday, not due to the destruction of time but the efforts exerted to resist it.

“It had been restored under the Soviets pitilessly,” Colin Thubron writes in The Lost Heart of Asia, “its life washed away. Inside the ramparts, I felt, nothing had ever happened, nor ever would happen. The place might have been created on the instant, without a past.”

Other buildings had never been finished at all.

The truncated bulk of the Kalta Minor Minaret is the most obvious example. Commissioned by Mohammed Amin Khan in 1851, it was meant to be 70 metres tall, covered with glittering blue-green tiles in geometric patterns broken by bands with inscriptions in nastaliq, the old Persian font.

But the Khan met his maker on campaign in Persia in 1855, and construction stopped. Its growth spurt stopped at 26 metres, giving the Kalta Minor the fireplug build of a circus strongman, completely dominating the West Gate and Polvon Kori Street.

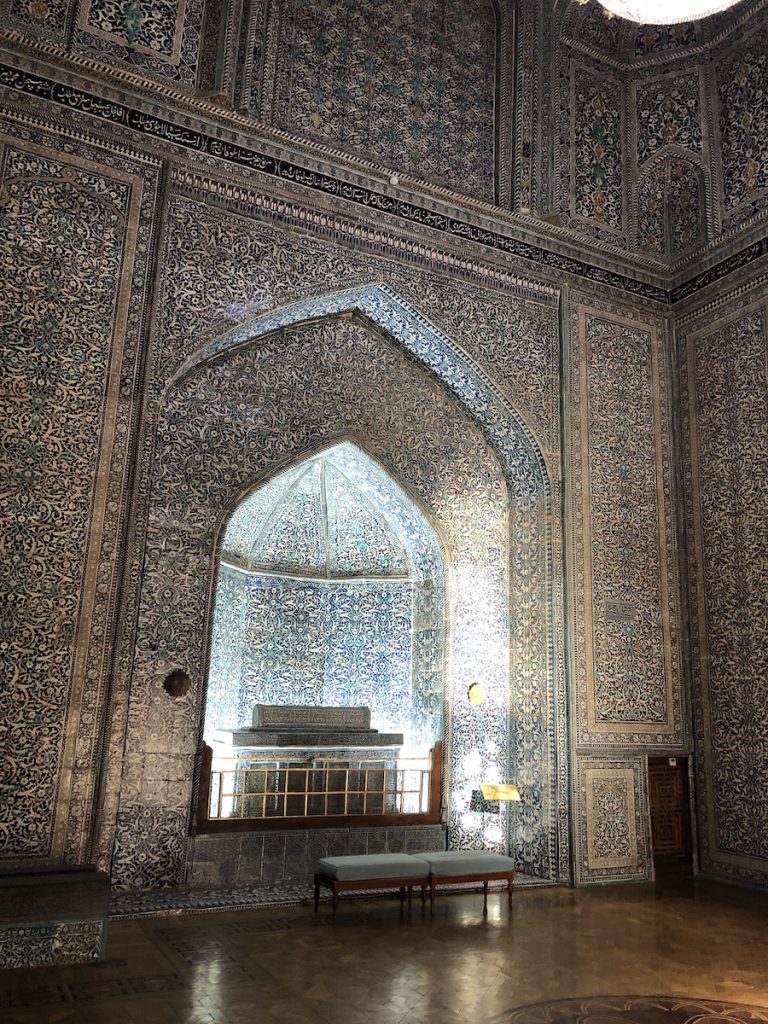

The town’s most impressive monument is surely the mausoleum of the Iranian wrestler, poet and later patron saint Pahlavan Mahmud ( (1247-1326).

Mahmud was revered by Khan Mohammad Rahim I (ruled 1806-1825) for his physical strength, Islamic piety and cultural sophistication. The powerful ruler beautified the tomb with a soaring chamber glistening in tiles and inscriptions of Mahmud’s poetry, topped with a brilliant blue Timurid dome.

The Khan put his own tomb in the main chamber and the poet’s off to the side. Later rulers added annexes of their own, transforming the complex into a dynastic burial place. The area around the building would eventually grow into a cemetery for Khiva’s elite.

A more egalitarian structure can be found a short block away. The 18th century Juma Mosque is a sheltered contrast to the city’s usual open air prayer spaces. The peaceful prayer hall, illuminated by two narrow light wells and an entrance on each side, is a maze of carved wooden pillars: 212 of them, the oldest dating back to the 10th century.

Its silence was a welcome respite from the stalls of souvenir vendors that crowd every open space and street in Khiva. Even the student’s rooms in the madrassas were full of them, all selling the same unremarkable junk.

I’ll have more to say about that invasion of lacklustre commerce later. We must now turn our attention to the madrassas because their sheer number gives us a sense of Khiva’s intellectual glory days.

There were around 65 madrassas in Khiva at the beginning of the 20th century — 54 of them inside the old town.

Built on the wealth of trade routes that spread ideas as well as goods, these venerable institutions didn’t just teach Islamic theology. Science, mathematics and philosophy were also core subjects during Central Asia’s Golden Age as the hub of world culture.

We can’t discuss all of Khiva’s remaining madrassas in the space of a blog, but I’ll tell you about a few of my favourites.

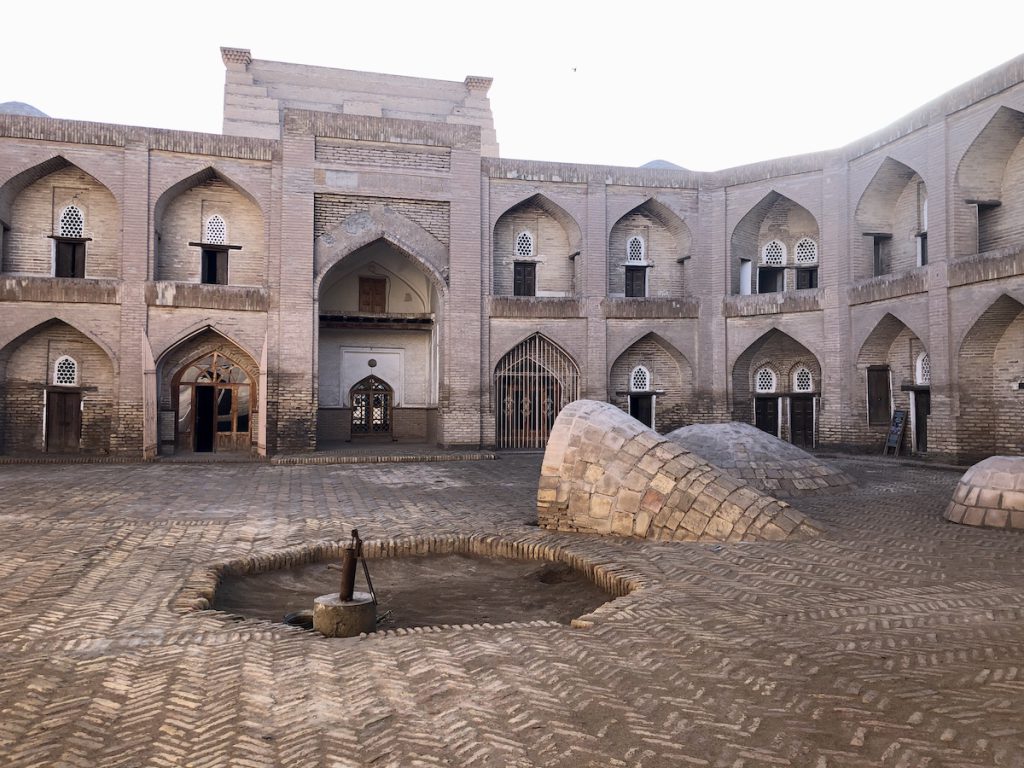

The wonderfully preserved Kutlug Murad Inaq Madrassa was built by the uncle of Alla Khuli Khan, with a large open courtyard surrounded by 81 student hujra (cells), and an underground cistern accessed by a steep flight of stone steps.

The courtyard also had a tightrope which I was told is used by a local family of acrobats for their practice sessions. Never one to let my readers down, I scaled the ladder like a monkey and dazzled the ladies with my high wire act.

Unfortunately, everyone was so mesmerized they forgot to take photos. But I can assure you it was a great high wire act. The best. And I never fell to my death even once.

Moving on….

Several other madrassas have been turned into small museums because they couldn’t find enough souvenir vendors to fill them.

The Abdullah Kaylan Madrassa contains a small natural history museum with displays on desert ecology and an alarmingly stuffed menagerie of animals in varying states of decrepitude.

If you look at maps as much as I do, you’ll know that Uzbekistan is one of just two double landlocked countries (the other is Liechtenstein). This led me to suspect the seagull as an interloper. I don’t know what he was doing there, but you can be sure he was up to no good.

Kazi Kaylan Madrassa (built in 1905) has a display of traditional Uzbek instruments and paintings of famous musicians. Two of the rooms have motion-activated sound systems which burst into song as you burst through the door, startling the bejesus out of timid travelers who lack the iron resolve of your narrator.

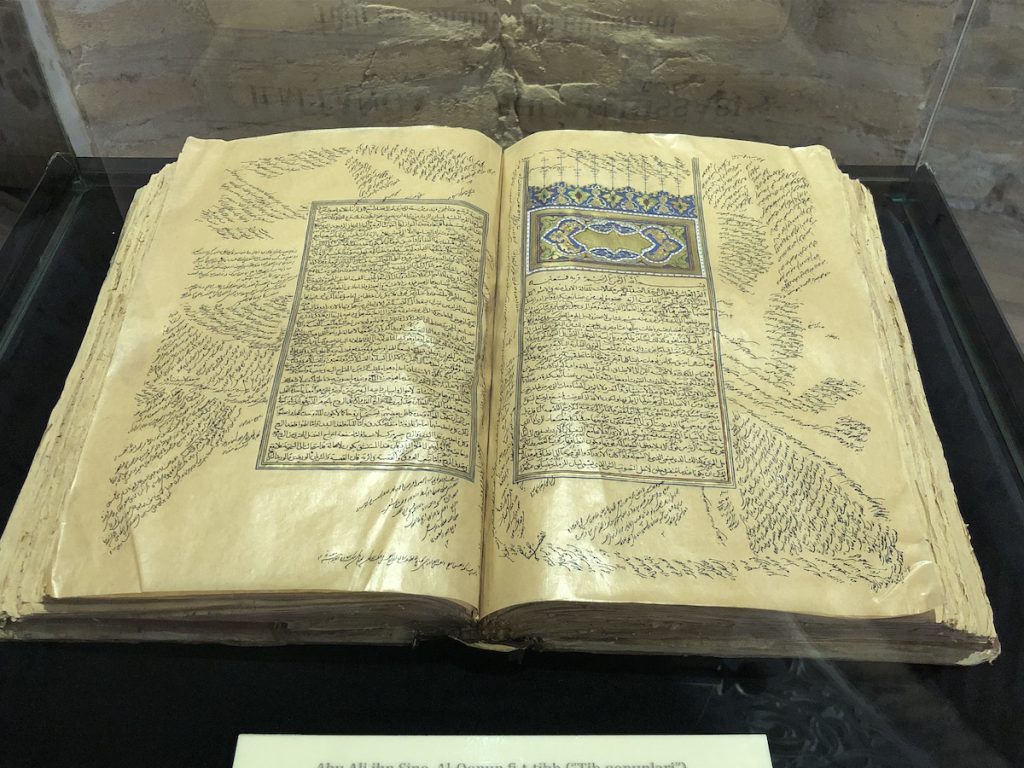

The enormous Shirgazi Khan Madrassa (1726), the oldest in Khiva, houses an extensive medical museum with frightening cases of surgical implements, and displays on Ibn Sina (980 – 1037), better known to the West as Avicenna.

This remarkable polymath from a village near Bukhara wrote some 450 works on astronomy, alchemy, geography and theology, but was best known for his work on philosophy and medicine. His Book of Healing and his five volume Canon of Medicine were standard texts at medieval universities, and were used in Europe as late as the 18th century.

The highlight for me was the Muhammed Amin Inaq Madrassa (1785), now a Museum of Scholars. I nearly didn’t go in because I heard it was a calligraphy museum, and I can’t read Arabic. We only stopped at the end of the day because it was part of our ticket.

The friendly staff was keen to show us two videos in English outlining Central Asia’s astonishing contributions to human knowledge. Much took place in the Samanid capital of Bukhara, a city we’ll visit in an upcoming blog. But the work of these key figures could be seen as representative of the region.

Among them we find al-Biruni (973–1048) from Khwarazm (north of Khiva). He made important contributions to astronomy and mathematics, including the first simple formula for measuring the Earth’s radius. He also introduced techniques to measure the earth and distances on it using triangulation

Ibn Iraq (950 – 1036) is best remembered for discovering the mathematical law of sines, one of two trigonometric equations applied to finding lengths and angles in triangles.

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780 – 850) — known as al-Khwarizmi — wrote groundbreaking books on mathematics, astronomy and geography. He’s known as the father of algebra for his pioneering treatise Al-Jabr (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing), and he developed a revolutionary technique for performing arithmetic with Hindu-Arabic numerals which would be called after a Latinized form of his name: the algorithm.

Those are just a few of the many madrassas you can explore in Khiva.

We were even staying in a madrassa of our own just outside the East Gate. It was built in 1905 by Polvon Qori, a wealthy merchant, with a 21-metre high minaret that we climbed after breakfast on our first morning.

The bed was incredibly hard — perhaps as a deliberate reference to the road of knowledge — but the little student cell was warm, a welcome shelter from the biting desert wind.

Unfortunately, no one will memorialize my time there with a psychedelic painting like al-Khwarizmi and al-Biruni.

I lack the theological grounding of even the worst-performing madrassa student. And when it comes to math, I count on my fingers.

It could be worse. My sister counted on her nose.

Photos © Tomoko Goto 2023