I went to Uzbekistan because I read a book twenty years ago that has always stayed in my mind.

The Great Game is a 19th century tale of espionage and exploration in the high mountain passes and deserts of Central Asia during a period of rivalry between Tsarist Russia and imperial Britain.

The Russians were spreading their influence south, and the British knew Afghanistan was just a short march from Delhi. The unmapped Pamirs, Karakoram and Himalaya on their northern flank might contain passes even more vulnerable than the Khyber..

Spies were dispatched to chart this territory disguised as holy men, counting their paces to map the distance, with hastily scrawled notes hidden inside prayer wheels and thermometers for calculating altitude sewn into sleeves. When they weren’t struggling for survival on the roof of the world, they were slipping into the world’s most dangerous oases to find out what their rivals were up to. It’s an incredible story with larger-than-life characters, and the inspiration for Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.

Some of these events took place in Bukhara, a place Colin Thubron described as “the most secretive and fanatical of the great caravan cities”.

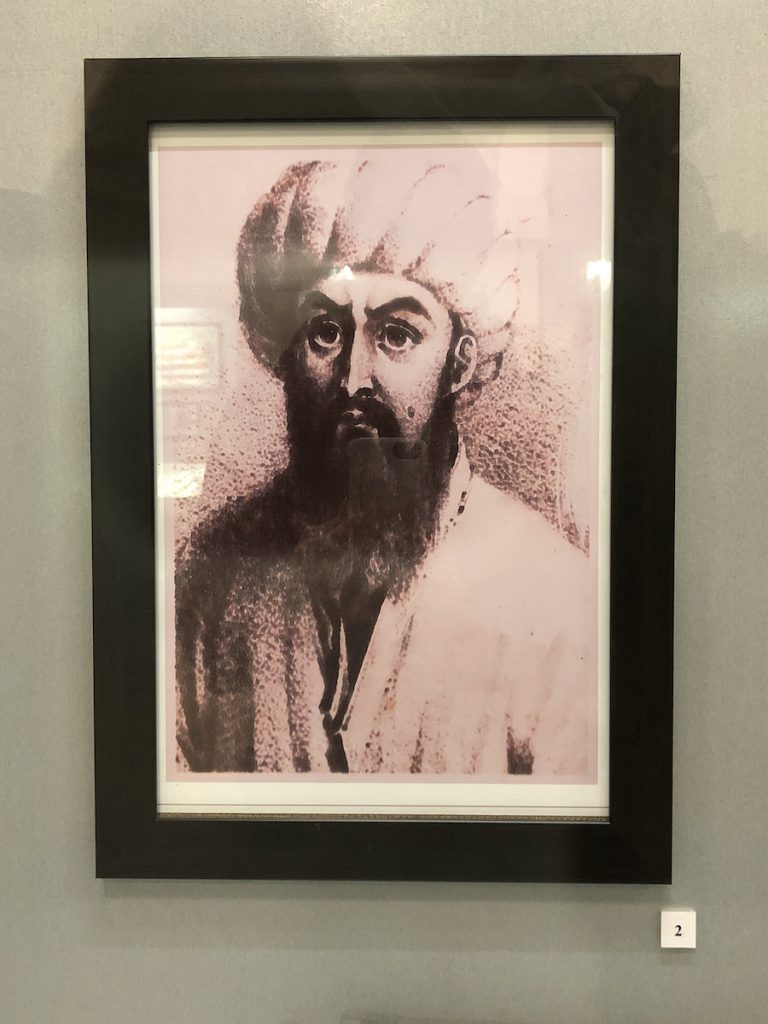

The story that intrigued me most occurred during the rein of Emir Nasrullah Khan. He’d come to power in 1827, heir of a father who had murdered his own brothers for the throne. Nasrullah studied the lesson well, bumping off so many rivals and dishing out punishments of such cruelty that he was known as “the Butcher”.

His favourite method of execution used Bukhara’s greatest landmark. The 47-metre high Kalon minaret (built in 1127) served as watchtower, beacon for desert caravans and final stop for those who’d gotten on the Emir’s bad side.

The criminal trudged up its 105 steps and stood, hooded and bound, as his sentence was read. Then would come a dreadful pause, followed by a scream as the condemned man was shoved off the edge to his death. Executions were held on market days so as many people as possible would witness them. The last took place in 1920.

Nasrullah was alarmed by British and Russian attempts to end Central Asia’s lucrative slave trade. He must have been in a foul mood when Colonel Charles Stoddart was sent to Bukhara in December 1838 to convince the Emir to throw in his lot with the British.

Stoddart was a brave and talented diplomat, but he hadn’t done his cultural homework. His first breach of etiquette was to ride straight up to the Emir’s palace in full regimentals rather than respectfully dismounting. Unfortunately for him, Nasrullah just happened to be returning at that moment. Stoddart saluted from his saddle in conformity with British military practice. Nasrullah fixed him with a steely glare and then rode on without a word.

When the Emir discovered that the letter carried by Stoddart was signed by the British governor of India rather than Queen Victoria — whom Nasrullah considered his equal — he had the British officer arrested, shackled and thrown into the Bug Pit.

The Emir’s jail was a miserable place, but the Bug Pit took incarceration to new depths. A 9-metre (29 feet) deep hole that could only be accessed by rope, it was littered with bones and human excrement, and crawling with insects, scorpions and rodents.

This imprisonment of a British officer caused a great outcry in England, but months passed with no sign of a rescue operation. Stoddart would spend nearly two years down there, being hauled up from time to time when he was briefly in the Emir’s erratic good books.

Captain Arthur Conolly, an experienced Asia traveler, was finally granted permission to seek Stoddart’s release. He reached Khiva in 1841, where the khan warned him to stay away from Bukhara, but Conolly would not be deterred.

The younger traveler was much more knowledgeable about court etiquette than the hapless Stoddart had been, but the suspicious Nasrullah still thought he was a spy sent to sow dissent between the region’s three powers: Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand. The Emir’s mood soured further when he learned the letter he’d sent to Queen Victoria had been handed off to the Governor-General of India. He threw Conolly into the Bug Pit too. The men would be kept there for another year.

When news reached Bukhara of Britain’s humiliating 1842 retreat from Afghanistan, Nasrullah decided the British were weak and had his two prisoners executed. Peter Hopkirk sketched the scene in his book The Great Game.

Stoddart and Conolly were hauled up from the Bug Pit, their bodies covered in sores, their clothing and beards crawling with lice. They were brought to the public square and ordered to dig their own graves as a silent crowd looked on. And then the two men were told to kneel and prepare for death.

Stoddard was the first to die, after denouncing Nasrullah’s tyranny. The executioner turned to Conolly and said the Emir offered to spare his life if he renounced Christianity and embraced Islam.

The solider said, “Colonel Stoddart has been a Mussulman for three years and you have killed him. I will not become one, and I am ready to die.”

He stretched out his neck for the executioner, and his head rolled in the dust.

Back in England, no one knew what had happened to the two men. When months passed without a letter, a well-known missionary called Dr. Joseph Wolff volunteered to travel to Central Asia to find out.

He arrived in Bukhara in 1843, and only survived because he turned up in Nasrullah’s throne room dressed in full canonicals, which caused the Emir to “shake with uncontrollable laughter” and send him back to London.

Wolff wrote a book about his experiences, where he described Nasrullah as a “cruel miscreant” and the execution of Stoddart and Conolly a “foul atrocity”. As for Nasrullah, he died in his bed in 1860.

The morning after our slow-train arrival, I took a Yandex taxi from our Air BnB flat to the city centre to see the spot where these events had played out.

The citadel brooded high on a hill, overlooking the square where the two Great Game travelers had been beheaded. The flat expanse of paving stone was surrounded by a metal barricade, with a Christmas tree in the centre and 8 or 9 red suited Santa-substitutes ho ho ho-ing around the edges. Santas who were not Santas at all, apparently, but had something to do with New Year.

We walked through the Ark’s tower-flanked entrance and trudged up the ramp to a cluster of buildings. The mosques, throne room and royal exhibits cast us back to Bukhara’s glory days. But the rest of the fortress was a vast rubble patch that resembled a First World War battlefield. It was bombed by Red Army aircraft and troops during the Russian Civil War.

I’d gotten a sense of how the cruel Emir lived, and I’d seen the square where Stoddart and Conolly met their end surrounded by a jeering crowd. All that was left was the jail.

We left the Ark and circumambulated its massive wall through a biting December wind to the Zindon. We had the entire structure to ourselves, with only a ticket seller hunched over a heater in a tiny room by the entrance.

The upper prison held crowded cells with debtors and other minor criminals who would be hauled out for public floggings.

Further in, beyond the guard rooms and the tax collector’s quarters, I found a narrow stone room with a square hole in the floor covered by a wooden grate.

The pit is much cleaner than it was in Nasrulla’s day. The stones are scrubbed and there aren’t any bugs. Deep in the hole, off to the side, a mannequin is slumped in a position of misery for the edification of visitors.

I stood for a long time staring into the pit, trying to imagine how hopeless it must feel to be left there wallowing in my own excrement as unspeakable things crawled over me in the dark.

How did they eat? How did they stay warm? And how did they survive for so long? Stoddart did two years in prison before Conolly was thrown in for another year.

The story didn’t end with their execution. Twenty years after their death, a parcel arrived at the London home of Conolly’s sister containing a prayer book that had been in her brother’s possession throughout his imprisonment. The margins and end papers were scrawled with tiny notes about his ordeal. The last one ended in mid-sentence. Unfortunately this book was subsequently lost and nothing has been heard of it since.

Isn’t it interesting how a book can spark a journey?

I first encountered the work of Peter Hopkirk in China’s far western Xinjiang province, somewhere south of the Taklamakan Desert. I’d met a fellow Canadian in a bar in Kashgar. Like me, he was desert-obsessed and searching for camels to hire. He was carrying a copy of Foreign Devils on the Silk Road. It spoke of lost cities buried beneath the sand, and the ancient manuscripts and paintings unearthed in this lost corner of the world.

I bought a copy not long after that 2002 journey, and I went on to read all of Peter Hopkirk’s books. I recommend you do the same. Start with The Great Game, or Trespassers on the Roof of the World.

Who knows? Maybe you’ll be hooked as deeply as I was, and you might make your own journey to Central Asia to look into the Bug Pit and think about the Great Game.

Photos © Tomoko Goto 2023