A great civilization existed in Khorezm from the 7th century BC to 1230 AD.

Its people farmed and traded in a broad river delta south of the Aral Sea, thriving for nearly 2,000 years between the Karakum and Kyzylkum deserts until Genghis Khan’s human storm swept in and put them all to the sword.

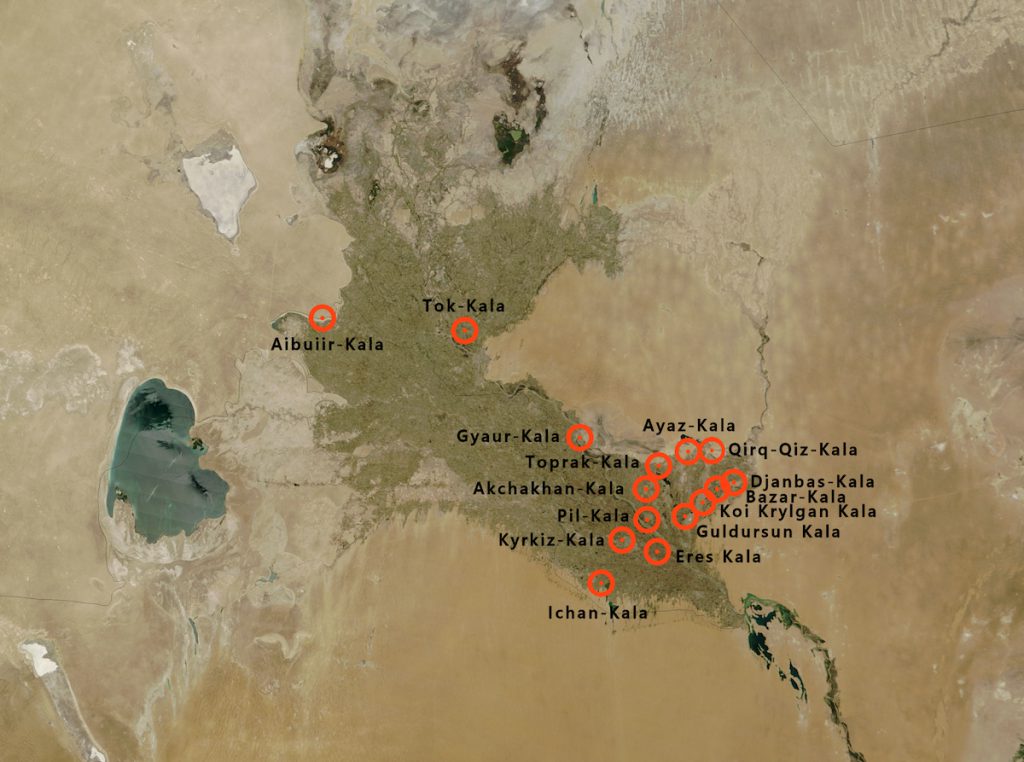

Today this desert is scattered with the ruins of more than 300 walled cities and fortifications, preserved for centuries by the region’s aridity but gradually melting back into the landscape. I hired a car and driver one day to track some of them down.

Dawn broke over stubbled fields as we crossed the Amu Darya River. I sat up straight and opened my window for a better look. This was the mighty Oxus: the river crossed by Alexander the Great and name checked by Robert Byron in his Road to Oxiana.

I’d seen cracked black and white photos of it in a palace in Khiva, taken at a time when its mighty flow, while not quite St. Lawrence in magnitude, made it one of the world’s great rivers. Today it’s a trickle broken into separate rivulets, drained nearly dry by the cotton fields of Soviet-era over-cultivation. Uzbekistan is still the world’s second largest exporter of the crop.

Beyond the bridge, sand and saxaul scrub alternated with narrow irrigation channels drained by rusting machinery into harvested fields of maize.

Each of the ten ruins we would encounter in the Khorezm region were very different. The first — Duman Kala — was little more than an eroded mound with the remains of a corner tower, but I felt the freedom of the desert flow through my veins as I scrambled up hardened sand and tried to avoid softer backsliding bits of dune.

Our second stop was much more imposing. Guldursun Kala was a 12th century fortified settlement that was occupied until 1220, when the Mongols arrived during the rule of Muhammad Khorezmshah.

It sat on the edge of a small farming town of mud brick huts and corrugated roofs. The massive 15 metre walls were almost fully intact, but it was only after we’d scrambled up the bank to a gap between watchtowers that we saw what a vast area it contained.

The interior was overrun with twiggy saxaul scrub that snagged our clothes and scraped our hands. An overgrown footpath cut across it to a gap in the opposite wall, where I saw another path running along the ramparts. After a bit of scrambling, I found several intact semi-circular watchtowers spaced at regular intervals down the external side, with commanding views over the farms below.

The 4th century BC Koi Krylgan Kala was a short desert drive away, and while there isn’t much to see beyond a dusty mound threaded with passageways, it is one of the most important ruins in the region because of its shape and use.

This was a round fortress some 90 metres in diameter formed of two concentric circles. The inner citadel, the section that’s still visible today, was a royal burial ground and ceremonial centre for cult rites, with servant’s and artisan’s rooms spreading towards the outer wall. Excavations in 1951 and 1952 uncovered rhytons (a conical container for drinking or pouring libations), plates and jugs with both animal and human reliefs, as well as terra-cotta figures of what seem to be gods or goddesses.

The site is badly eroded with little to see beyond the inner section. Our sudden arrival surprised a work crew who said they’d been sent to stabilize the walls and build an access path for tourists which would apparently be cut through at a spot chosen because it was nearest the road. They didn’t know much about Koi Krylgan Kala beyond that.

We drove north towards our next site, with a brief stop at Angka Kala, a 1st to 3rd century AD fortress that guarded the main eastward caravan route on the edge of Khorezm. The hallway-wide corridor between outer and inner walls was still clearly visible in places, with well formed arrow loopholes cut through the exterior wall.

Jambas Kala — a strange square spot of order on a barren upland — was visible from a great distance as we made our way across the desert. Built in the 4th century BC, its 20m high double walls are largely intact on all four sides, enclosing an area of 3.5 hectares, and showing a two-storey archer’s gallery with arrow slits top and bottom.

The site is believed to have held a garrison of 2,000 soldiers, with houses, bazaars and a fire temple. It differed from the other fortresses in having no towers on its outer walls. This archaic design and an absence of coins amongst its artifacts indicate that it belonged to the very distant past.

The lack of towers left its lower walls vulnerable, and this would be its downfall. Jambas Kala suffered repeated raids from hostile nomads who finally breached the wall in the 1st century BC. The enormous number of arrowheads unearthed inside testify to the ferocity of the struggle. Most of the inhabitants would have been killed, with survivors being taken as slaves.

Of all the fortresses we encountered that day, this one intrigued me most because so much of its walls were intact with traces of passageways, and because of its utter isolation.

Later we sat in the shelter of the wind-shaken car beneath walls that remained formidable despite erosion and the passage of time. Rahimbergan unwrapped a parcel on the front seat and opened a Tupperware container. He took a piece of grilled beef liver in his fingers and ate it, and held the container out to us, insisting we try some. A big piece of flatbread and a hardboiled egg followed. We hadn’t thought to pack a lunch; we had nothing to contribute in return except a handful of cookies we’d bought at the grocery store the evening before.

The next stretch of driving took us to our furthest point north. My wife dozed as I gazed out the window at small agricultural settlements that quickly gave way to open desert.

Big Kirkkiz Kala was built in the 4th century BC and abandoned and re-inhabited several times. Its last rulers were the Afrighids, who made it a centre of pottery production.

Disconnected sections of wall remain intact, but it was the vast area inside them that gave a sense of how many dwellings it must have contained. We wandered the interior with faces turned to the ground, bending to examine promising potsherds, until the cold wind urged us back to the car.

We were nearing the end of our desert journey, the perfect point at which to visit the most dramatically-sited ruin we would encounter.

Ayaz Kala is a complex of three clustered fortresses built in the 4th century BC on and around a dominant hill east of the Sultan Uvays Dag mountains.

We trudged to the top of the hill through windblown sand and entered the highest fortress at a narrow breach in walls topped with crenellated battlements broken by regularly-spaced curved towers.

The area within was a vast empty space, but the double walls held the remains of vaulted passageways most of which were nearly buried in sand. We followed them to the farthest corner and peered over the edge.

The gusting Kyzylkum Desert wind shook the mud wall beneath me as I squinted down at the second fortress, an oval structure with thick mud brick walls built atop a conical hill. It must have been a powerful citadel for the large palace at its foot. There was a third fortress not far beyond it —likely the oldest of the three — but little remains and we couldn’t see it from the hill.

The wine presses and golden statues unearthed there hint at Ayaz Kala’s wealth, but it, too, fell to the Mongols and vanished into the mists of time.

Our last stop would be two ruins in close proximity.

Built between the 1st and 4th centuries AD and rebuilt just before the Mongol invasions, scholars speculate Kizil Kala was either a garrison for troops attached to nearby Toprak Kala or an early fortified manor house.

It was interesting to examine its renovated mud brick walls coated in mud plaster mixed with straw in cross-section to get a sense of how these fortresses may have been constructed. But the heavy hand of the restorers had robbed the site of mystery.

Toprak Kala, four kilometres away, is far more alluring. The massive settlement was built in the Kushan period (2nd to 3rd centuries AD) as the royal residence of the Khorezm kings.

Some upper palace walls had been restored just enough to make out a complex of 150 rooms and passageways. Archaeologists identified several halls once adorned with bas-reliefs of shahs, warriors and goddesses. I found three niches in one of these rooms; one apparently held a depiction of the great goddess, with the other two housing god companions.

The palace was built in a corner of the walls at a height of 20 metres, wth the King’s Palace rising 15 metres above that. We wandered freely over the site, poking into rooms and crawling under arches, and climbing what’s left of three monumental towers.

The remains of the settlement spread out below us in a 175,000 square metre rectangular area enclosed by 9 metre high walls that circled the entire city and connected the entrance with the citadel.

We wandered the ruins until the light began to fade on the rocky spine of the Sultan Uvays Dag range, reminding us that it was time to climb back down for the long drive to Khiva.

We were leaving early the next morning on the slow cross-desert train.

Photos © Tomoko Goto 2023