My interest in Bukhara and Khiva centred on the Great Game. Samarkand is all about Timur.

The great Central Asian conqueror is known as Tamerlane in the West but he’s hardly a household name like Genghis Khan or Alexander. I’ll have more to say about him next week. Today I’d like to tell you about the rich architectural legacy he left behind.

Timur was born near Samarkand in 1336. After an unpromising beginning as a sheep rustler, he led his armies to the shores of the Mediterranean, to the edge of Moscow and over the Himalaya to Delhi in a remarkable lifelong saga of conquest, bringing riches, skilled craftsmen and scholars back to beautify his remarkable capital city.

He died, as he’d lived, in 1405 on his way to assail the Ming dynasty in China.

Timur was buried around the corner from our small family-owned hotel, and so I stopped to pay my respects on New Year’s Day. It was the first place in Uzbekistan where I’d encountered a significant number of tourists, perhaps due to being within a day’s drive of the capital.

The writer Justin Marozzi described this mausoleum as “the most inspired piece of Timurid architecture the world ever saw”.

Its magnificently-proportioned exterior is topped by a blue-tiled ribbed dome, and the interior walls are lavishly adorned with golden inscriptions and elegant turquoise arabesques. Timur’s stone is a massive single block of dark green jade at the centre, surrounded by descendants and placed, as was his wish, at the feet of his spiritual and religious mentor.

Like other Islamic tombs, the green stone is just a memorial. The conqueror’s bones lay in a vault beneath the mausoleum. I saw stone stairs around the back that ended at a barred door, but I wasn’t able to talk my way down with so many tourists loafing around.

The grave was opened in 1941 by Soviet archaeologist Mikhail Gerasimov, who confirmed that Timur was 5 feet 8 inches tall and lame in his right arm and leg. The arm had withered due to injuries, and the bone of his thigh had knitted together with his kneecap such that the leg was bent at all times, giving Timur a distinctive limp. It also gave him the mocking nickname ‘Timur the Lame’ or ‘Tamerlane’ but I doubt anyone said it to his face.

An oft repeated legend claims the tomb bore a warning: “When I rise from the dead, the world shall tremble”. When the sarcophagus was opened on June 19, 1941 they found another inscription inside: “Whomsoever opens my tomb shall unleash an invader more terrible than I”. Hitler invaded the Soviet Union three days later, on June 22. A superstitious Stalin demanded Timur be buried with full Islamic rites on December 20, 1942, a month before the Soviet victory at Stalingrad.

That’s the story, anyway, but we don’t know if it’s true.

I walked on up the hill to the Registan to see the madrassas his descendants had created. The British statesman and later Viceroy of India George Nathaniel Curzon called it “The noblest public square in the world”. Bounded on three sides by madrassa, all of them were heavily restored by Soviet archaeologists — perhaps a little too heavily, judging by old photos which show them as crumbling tile-less ruins.

The Ulugh Beg Madrassa (1417 – 1420) is the more impressive of the three, built during what became known as the Timurid era of architecture. Its enormous outer iwan was decorated with the usual geometric and floral tile work to which blue stars were added in reference to Ulugh Beg’s renown as an astronomer.

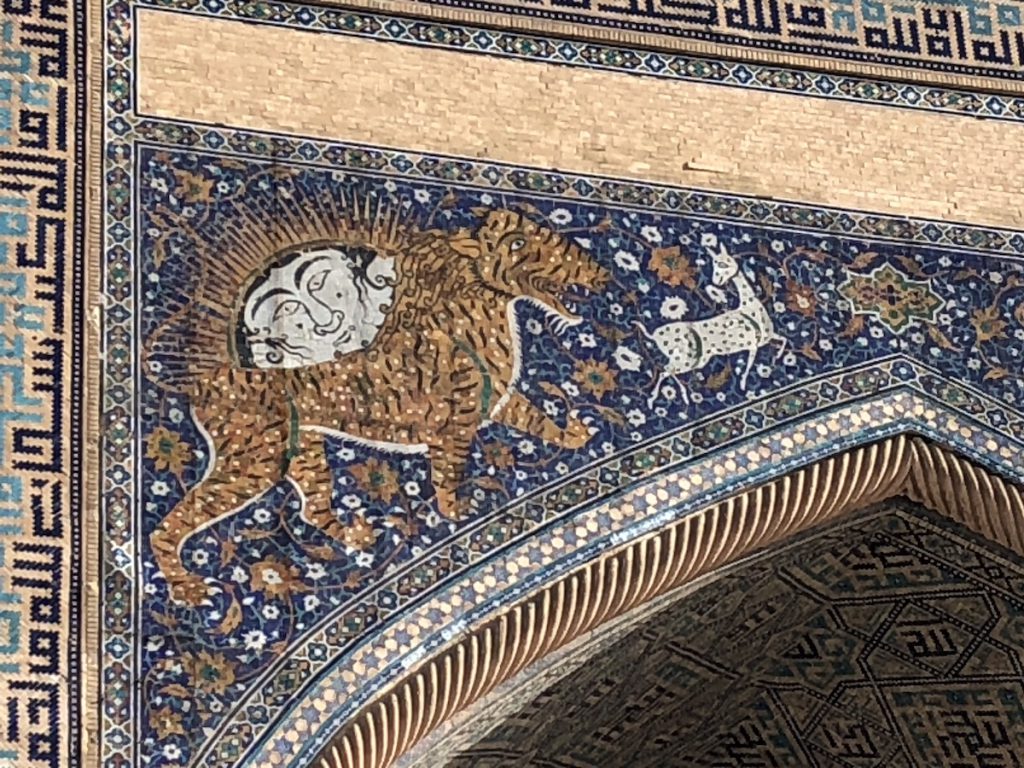

The Sher-Dor Madrassa (1619 – 1636) arrived more than a hundred years later. Its proportions are unremarkable but its tile work is a swirling growth of flowers and shoots, with two lions or tigers pursuing white does as suns with human faces rise over their backs — a break with the Islamic taboo against the depiction of live animals which legends say cost the architect his life. As for the suns, could they be a nod to pre-Muslim Zoroastrian symbolism? I suspect we’ll never know.

The Tilya-Kori Madrassa (1646 – 1660) was added ten years later to close off the far side. In addition to being a residential college, it housed a large mosque with a broad azure dome whose pale blue caught the winter sun and mirrored desert skies.

In the courtyard of all three buildings, every ground floor student cell had been crammed with souvenir stalls selling exactly the same wares I’d seen in Khiva and Bukhara. The only way to appreciate the space in silence was to stand exactly at the centre, equidistant from the cells, so the vendors would beckon someone else.

I don’t begrudge their attempts to earn a living, but I do think a better balance could be found if the stalls were located outside historic structures rather than throughout them.

Down the street, a soft serve ice cream cone fortified us for the short walk to the Bibi-Khanym Mosque. The building of this enormous structure was set in motion after Timur’s 1399 campaign to India and was nearly complete when he returned in 1404, but the great conqueror wasn’t impressed. After demanding some sections be torn down and rebuilt on a larger scale, he took a personal interest in its progress, overseeing parts of the construction and urging on the workers.

It was meant to be his showcase, with a 38 metre tall entrance portal nearly as high as Bukhara’s Kalon Minaret. Unfortunately Timur’s architectural skills did not match his tactical genius. The entire edifice was so enormous that it pushed contemporary building techniques to their limit. Bricks began falling from the dome before construction had even finished. What’s left is rent by enormous cracks propped up by rusted metal bars and clamps.

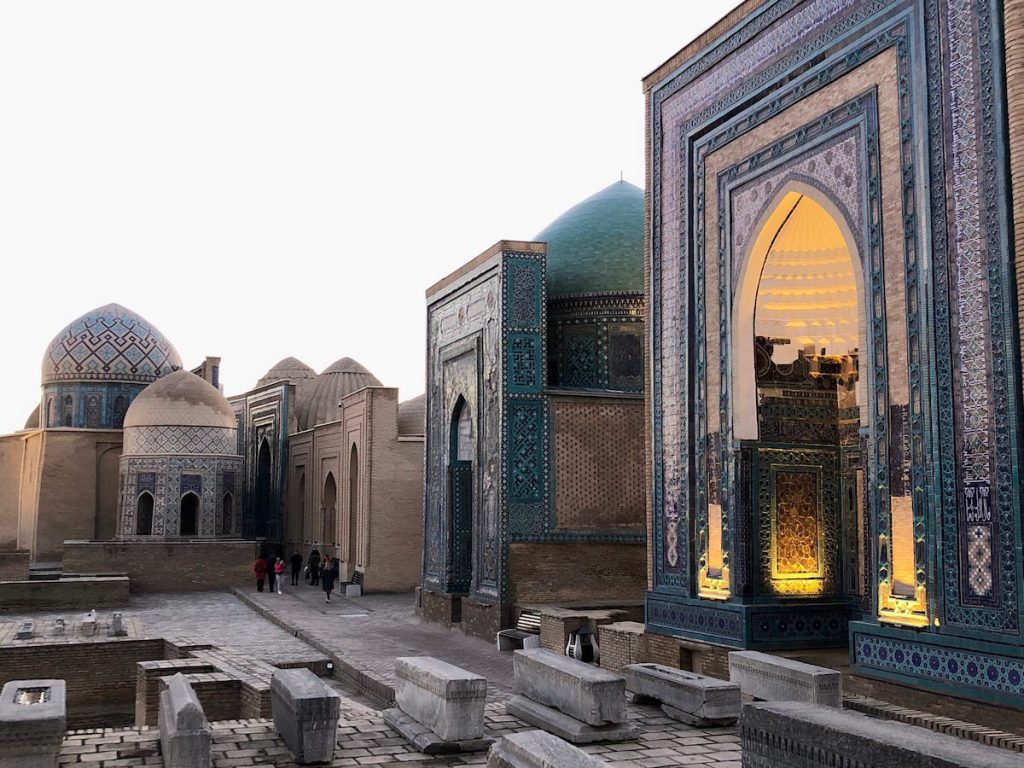

At the end of the street, beyond the ring road bridge, the mid-19th century Hazrat-Hizr Mosque offered views of the town from its hillside entrance portico. I spotted a cemetery in the distance, and we walked over to commune with the illustrious dead and some of the Muslim world’s richest tile work at the Shah-i-Zinda mausoleum complex.

Beyond the domed entry portal, a narrow street was shaded by closely built tombs decorated with intricate panels of carved and glazed terracotta, sheathed in tiles whose elaborate hexagrams and knotted borders resembled a carpet.

I pulled a dog-eared wad of stapled papers out of my pocket and read Justin Marozzi’s photocopied description of “spiralling floral patterns of blues, yellows, white and green vying for attention with scrolling vegetal decorations and the ornate ochre calligraphy running across the mosaics.”

The interred included Timur’s wet-nurse, his eldest sister, assorted wives and Kussam ibn Abbas, a cousin of the Prophet Mohammed who supposedly arrived in 676 brimming with missionary fervour. It wasn’t enough to convert the Zoroastrians, who promptly beheaded this messenger of god. The suddenly shortened missionary reportedly picked up his head and jumped down a well, where he’s been waiting for the right time to resume his reign while adding a pungent tang to the local water.

The sun sank across the city and set the tile work tombs ablaze in a brilliant reminder of a time when dusty desert Samarkand was the most cosmopolitan city in the world.

Its streets teemed with Muslim Turks and Arabs, Jacobites and Nestorian Christians, Zoroastrians and Jewish dyers, and its markets were stacked with the goods of the world. Precious stones competed with Chinese porcelain, Syrian metalware, Russian furs and Indian spices. Soaring above it all was a new and distinctively Central Asian creation: Timurid architecture that imposed clear geometric lines and lavish tile work onto monumental buildings.

But those prosperous days are lost in mists of time, somewhere beyond the Soviet era’s dull fug of boiled cabbage and broken dreams.

Our next day in the city wouldn’t be nearly as rewarding as that walk through Timur’s world.

At the remains of the observatory built by his grandson Ulugh Beg, we were charged 40,000 som to look at the scant remains of an astronomical instrument and a two-room museum with a general display on astronomy and government propaganda.

It felt like gouging of foreigners, but the Afrosiyab Museum was even worse: a 30,000 som foreigner price to squint at faded bits of a single mural, and a second floor that was the dusty remnant of a disassembled exhibit. Just around the corner, in a stairway that went nowhere, I found a pair of shoes and someone’s bedroll, with more shoes and clothing piled discretely behind empty display cases.

The entry fee included access to a vast open space where the remains of the original settlement of Samarkand once graced pre-Genghis-Khan Central Asia. There was nothing to see but piles of dirt, fluttering toilet paper and human turds. Go there if you need a long walk down an empty road to burn off some plov, but expect nothing for your entry fee — you will get nothing less.

Thankfully that isn’t the case with this website. Here you pay nothing and get so much more.

Timur is such a fascinating and under appreciated figure that I’ve devoted an entire Personal Landscapes podcast to his story. Stay tuned for that next week.

Photos © Tomoko Goto 2024

Get your FREE Guide to Creating Unique Travel Experiences today! And get out there and live your dreams...

3-13-24

I lived in Seattle for 15 years & my daily walk took me past new construction. It was my privilege to see a multistory bldg go from dirt to being occupied. The pictures of the madrassas & mausoleum’s are fantastic! How in the world were these structures built back in the day without cranes, heavy equipment etc is beyond my understanding. And the mosaic work is unbelievable. Thanks for sharing. There would never be a way I could see these places without your sharing.

Thank you Clark, I’m glad you’re enjoying these. It’s a great time to visit Uzbekistan. Travel there is easy and cheap, and people are incredibly helpful.

The mosaic and tile work is astonishing. Overwhelming in its opulence. And as you say, the scale of these entry portals conveys a sense of how small we are in the face of the knowledge taught within.