I told you about Mirian in my last blog — the driver we hired to visit two towns outside Tbilisi — and how intent he was to educate us about Georgia’s Atlantean origins, its remarkable fecundity in spawning the bloodlines of every royal family from Europe to Asia, and the mysterious way a baby can tap into universal truth. If only they had a larger vocabulary, we’d all be enlightened by now.

Traffic was heavy on the outskirts of Mtskheta but it soon thinned as we threaded the hills and entered open plains.

We were headed for the birthplace of one of history’s most ruthless mass murderers. For 30 years, this genial-looking man imposed a system of thought on his people and those of Eastern Europe that has caused more misery than any other bad idea in Western Civilization.

Only Chairman Mao would beat his body count, despite purges, executions and deliberately engineered famines. But some Georgians still saw him as a local boy who made it big. They clung to a myth in order to make sense of the past.

Nothing about Gori struck me as sinister as we rolled down a tree-lined road, past a mix of recent and Soviet-era buildings. It seemed like a pleasant place to wander on foot, and I regretted not having time to explore its old town and factory district.

Unfortunately, our days in Georgia were quickly coming to an end, and I wanted to see the Stalin Museum to get a sense of just how the hometown crowd chose to interpret ‘Uncle Joe’.

As I expected, it was a dusty hagiography housed in a stone-clad palazzo built in a style known as Stalinist Gothic.

We crept up the main marble staircase on a red carpet runner that led directly to a statue of the man himself, dressed in riding boots and his usual military-style tunic, gazing into the distance at the dystopian future he envisioned for humanity.

The first room focused on his early years as a seminary student turned communist activist, and his many arrests. There was even a mock-up model of the printing press he ran in Tbilisi, cranking out subversive pamphlets and newspapers calling for the overthrow of the Russian Tsar.

And then, somehow, Iosif Djugashvili became Joseph Stalin, with no mention of how he took power.

Then came a tedious stretch of photos of a genial-looking Stalin offering his infinite wisdom at tractor factories and farms, or bouncing children on his knee, some of which must have been done in between bloody purges.

The next room is devoted to the Second World War, where Stalin is presented as the hero who vanquished the Nazis, saving both the Soviet Union and Europe.

And then comes the climax of any devotee’s visit: the room where Stalin’s tastefully-lit death mask is displayed on a raised velvet cushion at the centre of a concrete colonnade.

There was nothing at all about show trials, purges, or paranoia, and not a single photo of Stalin’s fellow Georgian Lavrentiy Beria, his sadistic secret police chief.

As the visitor attempts to grapple with this life of utterly selfless service, he or she wanders through a room of gifts given to Stalin by other parts of the USSR and a few other countries. At least they kept it to one room, unlike the North Koreans, who dedicated a building each to gifts received by Kim il-Sung and Kim Jong-il.

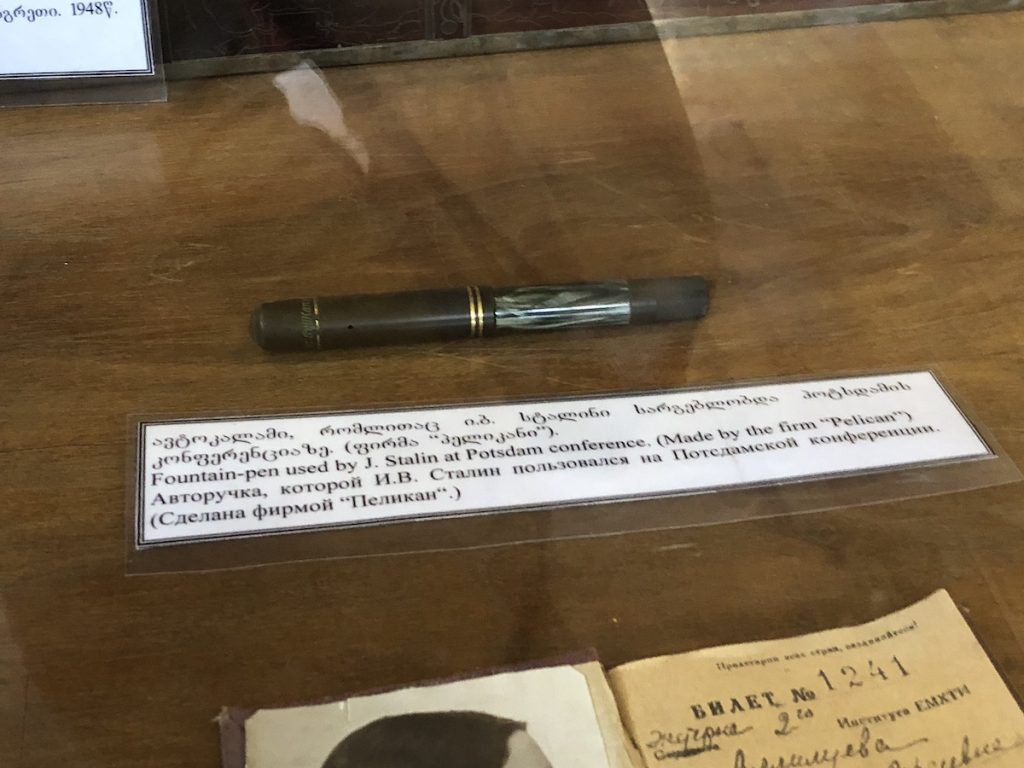

The final room displays Stalin memorabilia: his pipes, his desk, a clutch of dried up cigars, and the pen he used at Potsdam.

It was here I overheard an English-speaking tour guide admit ‘Uncle Joe’ had a darker side.

“Several places have museums that deal with the other side of this story,’ she said. “There are museums about the Soviet occupation and the KGB in Lithuania and Latvia, for example. And a museum about the famine in Ukraine. If you want to learn about those things, you can go to Riga or Vilnius. This museum focuses on the positive.”

In the central square beyond the exit, a small wooden hut said to be Stalin’s childhood home has been turned into a shrine, relocated to the grounds and protected from the elements by a Greco-Italianate marble pavilion.

Around the corner, the dictator’s 83 ton armour-plated Pullman railway carriage sits fading in the afternoon glare.

We were given a quick walk through it: past the guardroom and communications room, the lumpy bed and ensuite toilet with bath, and the conference table that was cooled by an early form of air conditioning. It was the same carriage he’d ridden to the Yalta Conference, and to Tehran.

I would have preferred to return to Tbilisi by train (unarmored), but Mirian was waiting for us on a side street, dozing peacefully beneath a tree in his car.

I asked him what Georgians thought of Stalin today.

“Many people see him as a big man who came from here and went on to lead the world’s biggest country,” he said. “The hero who defeated the Nazis. People see him differently because he brought economic benefits to Georgia during his time in power.”

Talk shifted to the current conflict, which Mirian claimed is a proxy war being fought by Ukrainians on behalf of the United States. According to him, America got involved because it is controlled by the Jews, who are somehow to blame for the war.

“Sanctions don’t work. Go to the Russian border with Georgia and look at the line of cars crossing in both directions.” He looked at me in the rearview mirror to emphasize his point. “There’s money to be made.”

“Ukrainians are stupid,” he said, because the country is a transit point for Russian goods and gas to Europe, and they could make money from this. “Instead, what do they have? A destroyed country.”

I thought it interesting that such an avowed Georgian patriot, who had regaled us with triumphant stories of how his countrymen had beaten back everyone from the Armenians to the Persians, would place profiteering over repelling an invasion when it comes to someone else’s country. And no matter how many mental contortions I imposed on my weary brain, I couldn’t figure out what Jewish people had to do with it.

The outskirts of Tbilisi came as a relief. When Mirian passed by the huge new cathedral on the hill, perhaps to emphasize some point about Mtskheta, we took it as an opportunity to put an end to this ride.

The Holy Trinity Cathedral is one of the world’s largest religious buildings by total area, but it felt utterly soulless compared to the churches we’d seen in Mtshketa, with a reek of Vegas about it.

We left after a quick look around and sought solace in a nearby cafe, where Lagidze water was dispensed from a soda fountain. This popular Georgian drink, invented by a pharmacist in 1887, is made by mixing natural syrups with soda water and serving on ice. I liked the shocking green tarragon flavour best, but you can also find quince, pear, cherry, lemon, and a sort of cream soda.

My throat felt like a lime kiln, but a glass of tarragon gave me the boost I needed to stumble down the hill to the old town, where we shuffled the streets beneath a blowtorch sky and poked into the cool of churches.

There wasn’t much to eat over there amidst souvenir shops and tourist trap restaurants, where hovering touts clutched menus by the entrance. And so we caught a Bolt ride over the river to another cheap basement diner on Aghmashenebeli Avenue, this one serving Rachan food.

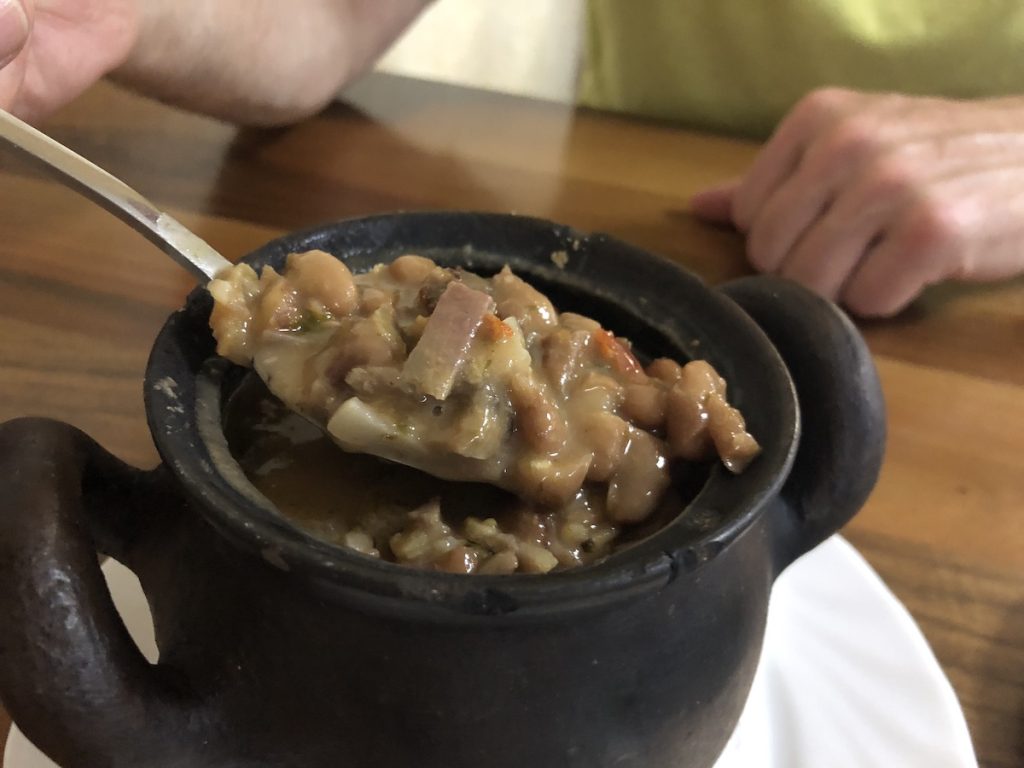

I ordered lobio with a side of mchadi (corn bread).

“Ahh, you know how to eat lobio!” the woman said with a nod of reappraisal.

I’d heard this dish was especially good here, where they served the usual clay pot of beans and herbs with chunks of smoky salted ham.

The main course could only be Skhmeruli: a whole pan-roasted chicken boiled in a garlic sauce. I’d read an article where the chef at Ghebi had shunned the more typical version of Skhmeruli that includes a splash of milk or cream — a variation he described as “a city thing”. When our chicken arrived in a sizzling platter, it was absolutely smothered in minced garlic.

We decided to walk back to our apartment off Rustaveli Avenue in the hope that a little exercise would relieve our straining waistbands.

As we made our way down a street bustling with Gulf Arab tourists and resident Indians, past a cafe strip of shisha bars, I heard my wife muttering about my choice of food: beans and garlic, two items guaranteed to induce gas in my innards of a type that would be viewed as a drastic escalation even on the Ypres salient.

History would prove her right. But at least we had high ceilings.

Photos © Tomoko Goto 2023